Hiroshima, 70 Years After the Atomic Bombing: Rebirth of the City, Part 1 [5]

Jul. 29, 2015

Part 1 [5]: Post office workers struggle to maintain mail service in ruined city

by Masanori Wada, Staff Writer

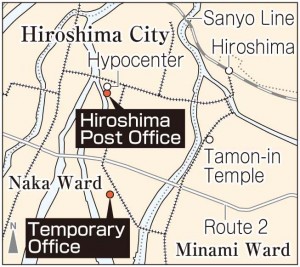

Inscribed on the back of a granite monument are the names of more than 200 victims of the atomic bombing. The three-meter-tall Monument to the Employees of the Hiroshima Post Office stands at Tamon-in Temple in Minami Ward. Every summer, Yasuyuki Uemoto, 89, pays a visit to this monument. Mr. Uemoto, a former post office employee, said, “My coworkers were erased by just one pikadon,” using an onomatopoeic expression for the atomic bomb. The deaths of post office workers meant that people living outside the city of Hiroshima had no way of confirming the safety of family members or friends by mail.

Stamped “Not delivered due to disaster”

In 1942, Mr. Uemoto began working for the Hiroshima Post Office, under the Ministry of Communications. The three-story brick building had a clock on its outer wall and was a landmark in Saiku-machi, not far from today’s Atomic Bomb Dome. Because the building was right beneath the exploding bomb, it was reduced to ashes on August 6, 1945. Of the 400 employees and students who were working for the post office, 215 that were in the building that day are believed to have died in the blast. Mr. Uemoto, drafted into military service in April, escaped the bombing. On August 17, he returned to where the post office had stood and found only a sign which said that it had been relocated.

Five days after the bombing, a temporary site for the post office was made in Senda-machi (now part of Naka Ward). It was staffed by employees who survived because they were off duty that day. Workers from post offices in nearby cities and towns, including Iwakuni in Yamaguchi Prefecture, also came to Hiroshima to lend a hand. Amid the chaos, the post office employees put their trust in people wishing to withdraw money but having no passbook or personal seal. With many coming to withdraw money from their accounts, a long line of people formed.

The mail service, though, was a different story. Mr. Uemoto began working at the temporary office, sorting letters that came flooding in from around the country to confirm the safety of people living in Hiroshima. Not a single bicycle was available for mail carriers. Relying on their memory of locations in the city, they walked through the charred land and sought the places to which the letters were addressed. But most of these addresses had disappeared. The letters that could not be delivered were brought back to the post office. Mr. Uemoto rubber-stamped them to indicate that they were not delivered because of the disaster. They were then held at the post office for some time in hopes that the intended recipients might come to retrieve them.

By the autumn, many makeshift huts had been built in the central part of the city and there was no way of knowing who lived where. So the letters were classified according to neighborhood, and the leader of each neighborhood association, who knew the neighborhood well, delivered the letters. “We had nothing like cellular phones in those days,” said Mr. Uemoto. “We struggled to ensure that people had a means of communicating with each other.”

Monument erected with donations

In September 1946, the new post office building was constructed in Motomachi (part of today’s Naka Ward). In 1949, postage stamps commemorating the promulgation of the Hiroshima Peace Memorial City Construction Act were issued, and postcards for New Year’s greetings went on sale for the first time after the war.

In that year, Mr. Uemoto was transferred to the Hiroshima Communications Bureau (located in today’s Naka Ward). He was in charge of managing the supplies for the post offices within its jurisdiction. Uniforms for employees and bicycles for delivering mail were provided, and at the same time, more and more postboxes were placed around the city. “I guess things eased up a bit in people’s lives, and they finally managed to reach out to others. Those red postboxes standing in the ruins were like a symbol of a peaceful life,” Mr. Uemoto said.

August 6, 1953, was a special day for Mr. Uemoto. With donations from post office workers from around the country, the monument was erected at Tamon-in Temple. One of the names inscribed on the monument was that of Akira Kanehara, who joined the post office in the same year as Mr. Uemoto. Mr. Kanehara, just 18 at the time, abruptly lost his life to the atomic bomb.

“He had poor eyesight so he was exempt from military service.,” Mr. Uemoto recalled. He gave me words of encouragement when I was conscripted. I became a soldier and survived, but he died while working hard as a post office employee.” Whenever he visits the monument, Mr. Uemoto feels that he must continue conveying to others how the bomb cruelly annihilated his coworkers and workplace. At the same time, he recognizes how fortunate it is that people today can exchange letters so freely.

(Originally published on July 19, 2015)