Hiroshima, 70 Years After the Atomic Bombing: Rebirth of the City, Part 1 [7]

Jul. 31, 2015

Part 1 [7]: 12-year-old boy supports family by selling goods, contributes to growing marketplace

by Koji Higuchi, Staff Writer

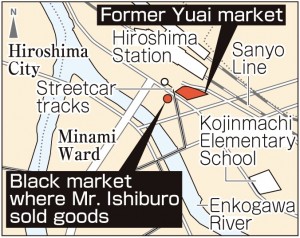

In late August 1945, about three weeks after the atomic bombing, stalls selling vegetables and other goods began to appear on the south side of Hiroshima Station. Thus began a thriving black market, which became the economic heart of the ruined city. In June 1946, a 12-year-old boy laid his goods on a straw mat and started selling them in the open-air market.

Selling a variety of things

“All I could think about was providing for my brothers and sisters,” said Akemi Ishiburo, 81. He said that the beginning of his venture as a shopkeeper was filled with such bitter experiences that he doesn’t want to recall them. The atomic bombing had forced him into this role.

Mr. Ishiburo grew up in a large family, with his parents and seven children. His parents ran a shop selling seaweed in Matsubara-cho (now part of Minami Ward). On the day of the bombing, his second eldest sister, then 17, went off to work and perished. His father, then 46, was on a rooftop and suffered burns all over his body. His mother, then, 41, was inside their shop and his eldest sister, then 19, was helping their mother. They all became bedridden after the A-bomb attack. Mr. Ishiburo returned home from the village of Kuji (now part of Asakita Ward), where he and other children had been evacuated earlier to avoid possible air raids on the city. As the eldest son, it was natural for him to begin selling what he could to support the family.

He lived temporarily with his uncle in today’s Kaita-cho and traveled back and forth by bicycle to the station. He would buy whatever goods he could get along the way and resell them. He sold seaweed, shiitake mushrooms, and food boiled in soy sauce that he bought from peddlers from around the country. Chocolate, chewing gum, and military uniforms he received from occupation soldiers stationed in Kaita sold well. He learned to set prices by watching the adults around him as they sold their wares.

But in the beginning, it was very hard to make ends meet, and one time hunger forced the family to eat weeds. In 1947, his parents and his eldest sister died, leaving behind five children.

In 1948, he built a two-story shack on the site where his parents’ shop had once stood and began to deal in dried food. But the following year, his shop was destroyed in a fire that engulfed the area.

Trouble at the marketplace

After he moved his shop to a local marketplace, he often encountered trouble. Adults picked fights with him. Once his aunt, Tomo, began to live with him and accompany him to work, she would yell at these adults and get rid of them. (Tomo died in 1984 at the age of 93.) Mr. Ishiburo eventually got married, had a son and a daughter, and worked hard to make his business a success. He opened a shop in the Kojin Market, which later became the Yuai Market, in a prime location in front of the train station. In 1999, he came down with cancer and his younger brother took over the business, but Mr. Ishiburo helped in the shop until it closed in 2013 when a redevelopment project shuttered the market.

“I chose this work not because I liked it, but I couldn’t afford to become overwhelmed with grief,” he said. As the black market evolved into a proper marketplace, the area around the train station became a busy shopping district. The prosperity of the area was fueled by the hungry spirits of the shopkeepers, including Mr. Ishiburo. The success of the market in front of the station led to the development of other shopping areas in the city, such as the Hondori shopping district, which was reconstructed in 1946, and the Takanobashi shopping district, where merchants also profited from conducting wholesale business with the shops around the station.

Mr. Ishiburo still lives near Hiroshima Station. With the area now undergoing a major redevelopment project, he can hear the hammering sounds from the construction site where a high-rise building will be completed next year. As he observes the changing cityscape, he holds no deep emotional attachment to the thriving old marketplace. “Times have changed,” he said, “and the area has a different role to play now.” He hopes that the area will become a livelier part of the city and that the station district, which supported the lives of citizens in the aftermath of the war, will continue to thrive in the peaceful city of Hiroshima.

(Originally published on July 21, 2015)