Interview with A-bomb survivor Sunao Tsuboi: Never give up on nuclear abolition

Aug. 6, 2015

by Uzaemonnaotsuka Tokai, Editorial Writer

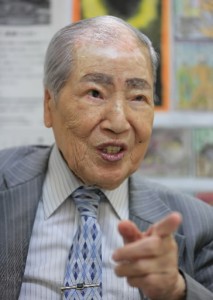

Seventy years have passed since the harrowing events of the atomic bombings. The survivors have suffered from the fear of disease and death, and wrongheaded prejudice, but have nevertheless continued to call for the abolition of nuclear weapons out of their belief that no others should be forced to endure the same fate. Their movement, though, has now come to a crossroads. Sunao Tsuboi, 90, co-chairperson of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), is the “face” of Hiroshima and still leads the survivors’ movement despite his advanced age. How can we hand down the A-bomb experiences? How should we interpret the current state of affairs in Japan, where the nation’s vow never to repeat the tragedy of war seems in danger of being undermined? The Chugoku Shimbun discussed such concerns with Mr. Tsuboi.

Could you describe what you experienced on August 6?

After having breakfast, I was on my way to the university where I was a student, the Hiroshima Technical Institute in Senda-machi. I was in the Fujimi-cho district, about 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. I heard a big whooshing sound above me, to the left. I thought it was a bomb and I covered my face with my hands. There was a flash, like a great many camera flashes going off at once.

As I was bathed in this silver-white light, I heard a tremendous boom. Before I knew it, I was blown several meters through the air. With all the smoke and dust, I couldn’t see. I didn’t know which way I should flee. And I realized that my clothes were tattered and my arm was bleeding badly. Dark red blood was streaming from my waist.

Do you recall what your surroundings were like?

There was no sound at all. There was only silence, all around. Even the cicadas had stopped buzzing. When I managed to start walking, I saw scenes from hell. I saw a female student whose right eyeball was dangling around her cheek, and it jiggled with each step she took. I also saw a woman who was running for refuge as she pressed on her intestines, which were protruding from her body. Many of the people I saw, I couldn’t even recognize where their faces or heads were. People were crying for help, too. I felt sorry for them, but there was nothing I could do.

You were at the end of Miyuki Bridge, where a historic photo was taken three hours after the atomic bombing by the late Yoshito Matsushige, a photographer for the Chugoku Shimbun.

I heard a first-aid station had been set up there, and I practically crawled to reach it. But I didn’t find one. I thought this would be the end for me. I collapsed to the ground and prepared to die. I took a small rock and scratched “Tsuboi died here” into the dirt. I wanted to leave a mark that this was where I died. It was a farewell message.

How did you survive?

By chance, I came across some civil defense volunteers and my classmates, and they saved me. I was taken to a temporary field hospital on Ninoshima Island. I guess there were about 100 people in a place the size of a classroom. About 80 percent of them were dead by the following morning. I was unconscious until my mother came to look for me from my hometown of Ondo. I heard she searched for me frantically, calling my name over and over. And I was told I raised my hand as if to say “Here I am,” even though I was unconscious. That’s how I survived, thanks to my mother’s love.

What led you to join the survivors’ movement after the war?

After my injuries were treated, I became a junior high school teacher. I always shared my A-bomb experience with my students so my nickname became “Mr. Pikadon.” [The Japanese term “pikadon” is a combination of the words for the flash, “pika,” and boom, “don,” of the atomic bomb.] But it was after I retired that I got involved in the peace movement. I couldn’t turn down a friend’s request. The people around me had always lent their support so I wanted to repay that debt. Back then, only one percent of applicants were recognized as sufferers of A-bomb diseases. So Nihon Hidankyo led class action lawsuits over this issue, and the criteria for certifying A-bomb diseases were relaxed. The relief measures have improved, but it’s still not enough. If I just tell people “It was so hard,” or “It was hell,” my story is simply a tearjerker. It’s important to take the opportunity presented by the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings and demand that nuclear weapons be abolished.

How can the survivors’ movement be strengthened despite the advancing age of the survivors?

Sooner or later, the survivors will be gone. This is inevitable. The survivors themselves can’t continue their movement forever. I hope, though, that their children and grandchildren will take up our efforts. The names of the survivors’ groups will also change, to something like “peace promotion council.” I imagine the word “hibakusha” (“survivor”) won’t be included any more. These groups in the future should be composed of a wider range of people who want to advance the abolition of nuclear arms.

Survivors can still play an important role, considering the current international conditions involving nuclear issues.

There have been ups and downs in these global conditions. I clapped and cheered when the International Court of Justice determined that the use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law. I was impressed by the speech President Obama made in Prague. But this year’s Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) failed to reach an agreement. Things don’t always work out as we wish. But I’m not pessimistic. Nuclear abolition will be realized someday.

The Japanese government says that it will play a leading role in nuclear abolition, but this pledge is being called into question.

Frankly speaking, I’m not happy about the government’s attitude. It opposes a nuclear weapons convention. The government says it will call for nuclear abolition, but it still follows the lead of the United States while under the U.S. nuclear umbrella. The attitude is always, “Let’s wait and see how things go.” It’s disgraceful and it gets me frustrated. To top it all, the government is now trying to take the tooth out of Article 9 of the Constitution.

You mean the security bills.

This is too big a change to be made by the force of greater numbers in the ruling coalition. Most scholars say that the bills are unconstitutional, so it’s wrong to change the interpretation of the Constitution. It’s not a question of how much discussion time there is; a hundred hours of discussion isn’t the point. If the government wants to protect this nation, it should, above all, address problems through diplomacy. If they want to prepare for further recourse beyond that, the politicians themselves should sign and seal a written promise that they will be the first ones to go to wherever armed forces are used, in this event. Seventy years ago, we were told to protect our country and we were pulled into war. Then the atomic bombs were dropped. After the war, we were told that nothing could have prevented the atomic bombings because they took place during wartime. Today’s politicians don’t understand this at all. I’m afraid this nation could again become a country that wages war.

You have said that the 70th year since the atomic bombings will be a major milestone for you. How do you feel now?

I sometimes look at the photo taken at Miyuki Bridge. I was 20 and I thought I would die. I was between life and death. That photo stirs something deep inside me. Seventy years have passed since then. I’ve done well, I think. After the atomic bombing, many people extended helping hands to me. I just want to repay their kindness, which is a force that has empowered my life. I was hospitalized many times, and three times I was in critical condition. But I always joked about it, saying things like, “They’ll put me in my casket soon.” To be honest, in my mind was the thought, “I survived the atomic bombing. How can I die from just a disease!”

But these days I can’t move around as freely as I’d like. I thought, with this interview, I can leave my will. I’ve lived a long time and endured many hardships. I truly hope to see nuclear weapons abolished. But if I can’t witness this, future generations will achieve our aim. I leave the rest to you, young people. You must not give up. No, never give up!

Profile

Sunao Tsuboi

Born in the Ondo district in the city of Kure in 1925. Experienced the atomic bombing in Fujimi-cho, 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, while a third-year student at the Hiroshima Technical Institute (now, the Faculty of Engineering at Hiroshima University). Worked as a junior high school teacher and principal. Became secretary general of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations in 1994 and its chairman in 2004. Co-chairperson of the Japanese Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organization since 2000.

(Originally published on August 2, 2015)

Seventy years have passed since the harrowing events of the atomic bombings. The survivors have suffered from the fear of disease and death, and wrongheaded prejudice, but have nevertheless continued to call for the abolition of nuclear weapons out of their belief that no others should be forced to endure the same fate. Their movement, though, has now come to a crossroads. Sunao Tsuboi, 90, co-chairperson of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), is the “face” of Hiroshima and still leads the survivors’ movement despite his advanced age. How can we hand down the A-bomb experiences? How should we interpret the current state of affairs in Japan, where the nation’s vow never to repeat the tragedy of war seems in danger of being undermined? The Chugoku Shimbun discussed such concerns with Mr. Tsuboi.

Could you describe what you experienced on August 6?

After having breakfast, I was on my way to the university where I was a student, the Hiroshima Technical Institute in Senda-machi. I was in the Fujimi-cho district, about 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. I heard a big whooshing sound above me, to the left. I thought it was a bomb and I covered my face with my hands. There was a flash, like a great many camera flashes going off at once.

As I was bathed in this silver-white light, I heard a tremendous boom. Before I knew it, I was blown several meters through the air. With all the smoke and dust, I couldn’t see. I didn’t know which way I should flee. And I realized that my clothes were tattered and my arm was bleeding badly. Dark red blood was streaming from my waist.

Do you recall what your surroundings were like?

There was no sound at all. There was only silence, all around. Even the cicadas had stopped buzzing. When I managed to start walking, I saw scenes from hell. I saw a female student whose right eyeball was dangling around her cheek, and it jiggled with each step she took. I also saw a woman who was running for refuge as she pressed on her intestines, which were protruding from her body. Many of the people I saw, I couldn’t even recognize where their faces or heads were. People were crying for help, too. I felt sorry for them, but there was nothing I could do.

Prepared to die

You were at the end of Miyuki Bridge, where a historic photo was taken three hours after the atomic bombing by the late Yoshito Matsushige, a photographer for the Chugoku Shimbun.

I heard a first-aid station had been set up there, and I practically crawled to reach it. But I didn’t find one. I thought this would be the end for me. I collapsed to the ground and prepared to die. I took a small rock and scratched “Tsuboi died here” into the dirt. I wanted to leave a mark that this was where I died. It was a farewell message.

How did you survive?

By chance, I came across some civil defense volunteers and my classmates, and they saved me. I was taken to a temporary field hospital on Ninoshima Island. I guess there were about 100 people in a place the size of a classroom. About 80 percent of them were dead by the following morning. I was unconscious until my mother came to look for me from my hometown of Ondo. I heard she searched for me frantically, calling my name over and over. And I was told I raised my hand as if to say “Here I am,” even though I was unconscious. That’s how I survived, thanks to my mother’s love.

What led you to join the survivors’ movement after the war?

After my injuries were treated, I became a junior high school teacher. I always shared my A-bomb experience with my students so my nickname became “Mr. Pikadon.” [The Japanese term “pikadon” is a combination of the words for the flash, “pika,” and boom, “don,” of the atomic bomb.] But it was after I retired that I got involved in the peace movement. I couldn’t turn down a friend’s request. The people around me had always lent their support so I wanted to repay that debt. Back then, only one percent of applicants were recognized as sufferers of A-bomb diseases. So Nihon Hidankyo led class action lawsuits over this issue, and the criteria for certifying A-bomb diseases were relaxed. The relief measures have improved, but it’s still not enough. If I just tell people “It was so hard,” or “It was hell,” my story is simply a tearjerker. It’s important to take the opportunity presented by the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombings and demand that nuclear weapons be abolished.

How can the survivors’ movement be strengthened despite the advancing age of the survivors?

Sooner or later, the survivors will be gone. This is inevitable. The survivors themselves can’t continue their movement forever. I hope, though, that their children and grandchildren will take up our efforts. The names of the survivors’ groups will also change, to something like “peace promotion council.” I imagine the word “hibakusha” (“survivor”) won’t be included any more. These groups in the future should be composed of a wider range of people who want to advance the abolition of nuclear arms.

Not pessimistic

Survivors can still play an important role, considering the current international conditions involving nuclear issues.

There have been ups and downs in these global conditions. I clapped and cheered when the International Court of Justice determined that the use of nuclear weapons would generally be contrary to the rules of international law. I was impressed by the speech President Obama made in Prague. But this year’s Review Conference of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT) failed to reach an agreement. Things don’t always work out as we wish. But I’m not pessimistic. Nuclear abolition will be realized someday.

The Japanese government says that it will play a leading role in nuclear abolition, but this pledge is being called into question.

Frankly speaking, I’m not happy about the government’s attitude. It opposes a nuclear weapons convention. The government says it will call for nuclear abolition, but it still follows the lead of the United States while under the U.S. nuclear umbrella. The attitude is always, “Let’s wait and see how things go.” It’s disgraceful and it gets me frustrated. To top it all, the government is now trying to take the tooth out of Article 9 of the Constitution.

You mean the security bills.

This is too big a change to be made by the force of greater numbers in the ruling coalition. Most scholars say that the bills are unconstitutional, so it’s wrong to change the interpretation of the Constitution. It’s not a question of how much discussion time there is; a hundred hours of discussion isn’t the point. If the government wants to protect this nation, it should, above all, address problems through diplomacy. If they want to prepare for further recourse beyond that, the politicians themselves should sign and seal a written promise that they will be the first ones to go to wherever armed forces are used, in this event. Seventy years ago, we were told to protect our country and we were pulled into war. Then the atomic bombs were dropped. After the war, we were told that nothing could have prevented the atomic bombings because they took place during wartime. Today’s politicians don’t understand this at all. I’m afraid this nation could again become a country that wages war.

Leaving his will to the future

You have said that the 70th year since the atomic bombings will be a major milestone for you. How do you feel now?

I sometimes look at the photo taken at Miyuki Bridge. I was 20 and I thought I would die. I was between life and death. That photo stirs something deep inside me. Seventy years have passed since then. I’ve done well, I think. After the atomic bombing, many people extended helping hands to me. I just want to repay their kindness, which is a force that has empowered my life. I was hospitalized many times, and three times I was in critical condition. But I always joked about it, saying things like, “They’ll put me in my casket soon.” To be honest, in my mind was the thought, “I survived the atomic bombing. How can I die from just a disease!”

But these days I can’t move around as freely as I’d like. I thought, with this interview, I can leave my will. I’ve lived a long time and endured many hardships. I truly hope to see nuclear weapons abolished. But if I can’t witness this, future generations will achieve our aim. I leave the rest to you, young people. You must not give up. No, never give up!

Profile

Sunao Tsuboi

Born in the Ondo district in the city of Kure in 1925. Experienced the atomic bombing in Fujimi-cho, 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter, while a third-year student at the Hiroshima Technical Institute (now, the Faculty of Engineering at Hiroshima University). Worked as a junior high school teacher and principal. Became secretary general of the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations in 1994 and its chairman in 2004. Co-chairperson of the Japanese Confederation of A- and H-bomb Sufferers Organization since 2000.

(Originally published on August 2, 2015)