Yoko Yoshii, resident of Naka Ward

Sep. 3, 2015

Memories of A-bomb aftermath, fears of discrimination

by Koji Higuchi, Staff Writer

Yoko Yoshii (nee Oda), 85, still feels a pang of regret when she scoops water to wash her face. “If I had put my hands together tighter, the water wouldn’t have leaked out.” In the aftermath of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, while she was walking through the city center toward a safer suburban area, someone lying on the street called to her, asking for water.

She had heard the caution, back then, that those with burns from the A-bomb blast should not be given water. But the woman was dying, and Ms. Yoshii wanted to fulfill her last request. She tried carrying over some warm water that was spewing from a broken water pipe, yet the water ran through her fingers. All she could do was moisten the woman’s lips. The woman’s burnt skin had peeled away from the flesh and was dangling from her arms. Ms. Yoshii is unable to forget the look on her face when she begged for water.

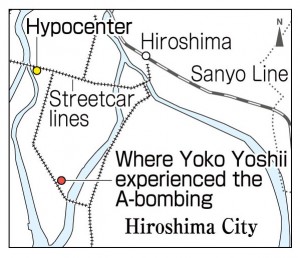

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Yoshii was 14 and a third-year student at Hiroshima Second Municipal Girls' High School (now Funairi High School). She was exposed to the flash of the atomic bomb in Senda-machi, about 1.9 kilometers from the hypocenter. As a mobilized student, she usually worked at the Hiroshima plant of the Japan Steel Works, helping produce cast-metal parts. But the plant was closed on August 6 because of an electric power shortage. She left her home in Kabe (now part of Asakita Ward) for school in Midori-machi (now part of Minami Ward), taking a train and a streetcar. When she got off the streetcar in front of the head office of the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company, she saw a flash in the sky.

After lying on her stomach for some time, she opened her eyes. She saw people and horse carts fallen flat on the ground. She also saw fires. She was not seriously injured, probably because she was behind the building of the railway company. She and her classmates fled through Kamiya-cho and Nakahiro-cho (in today’s Naka Ward and Nishi Ward, respectively) to a bamboo grove in the Mitaki area (part of today’s Nishi Ward). Along the way they saw people begging for water.

As night came, Ms. Yoshii fell asleep before she knew it. There were many people in the bamboo grove. One man bravely sang military songs before he suddenly lost consciousness and died. On the following day, August 7, she walked to Furuichi (now part of Asaminami Ward), where she took a train to Kabe. In front of the train station were her parents, looking for her desperately and calling out, “Is Yoko Oda here?” She and her parents embraced one other and wept.

On the following day, Ms. Yoshii’s father headed for her aunt’s house near the Aioi Bridge, located close to the hypocenter, pulling a large two-wheeled cart. Only one other person from her family of seven managed to survive. An 8-year-old cousin died the day after he was brought to Ms. Yoshii’s home.

Several days after the bombing, Ms. Yoshii came down with a fever and began vomiting. Three or four months later, she lost all her hair. She spent more than three years at home to recuperate.

Ms. Yoshii still feels lethargic every summer. She developed breast cancer in her 70s. Her 65-year-old daughter suffers from thyroid abnormalities, and all three of her grandchildren are suspected of having thyroid dysfunction. She said, “If the damage of invisible radiation is passed onto them, it’s too much to bear.”

As she was fearful of discrimination, she kept to herself the fact that she was exposed to the atomic bomb. She married at the age of 18, but still kept this secret for a year. When she finally disclosed her experience to her husband, Masayuki Yoshii, he simply said, “That must have been very hard.” His sympathetic words saved her, she felt. Mr. Yoshii had been dispatched to China during the war, and she believes that, through his own experience, he had come to keenly realize the horror of war.

Ms. Yoshii is now very concerned about the new security bills sought by the prime minister and his administration. “It sounds like Japan would be waging war again, so I’m absolutely against these bills,” Ms. Yoshii said. “Japan hasn’t fought a war for the past 70 years. Never, ever allow this to change.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Eliminate discrimination against A-bomb survivors

Ms. Yoshii said she believed she wouldn’t have been able to marry if she revealed that she was exposed to the atomic bomb. When I heard this, I realized that there were many things that troubled the A-bomb survivors. We must treat people equally. Discrimination should be eliminated. I don’t judge people by their appearance, like the color of their skin. (Yui Morimoto, 11)

Impressed by love for one’s community

I was surprised to hear that Ms. Yoshii’s sister wouldn’t apply for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate because she didn’t want to cause trouble to her country. Those who cherish their country must also cherish their hometown and its people. I once joined a local effort to clean up the community, and I plan to take part in another. (Atsuhito Ito, 12)

Give consideration to other people’s feelings and act thoughtfully

I was impressed by Ms. Yoshii’s words: “Be polite and live in harmony with the people around you.” We can’t make a peaceful society when we fight with our friends or family members. I will begin with something close to me and widen the circle of peace. I will always greet and thank people properly and consider other people’s feelings and act thoughtfully. (Kohei Furohashi, 16)

(Originally published on August 18, 2015)