Park Namjoo, 82, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Sep. 17, 2015

A-bomb survivors from Japan and South Korea have suffered in the same ways

by Hidetoshi Arioka, Staff Writer

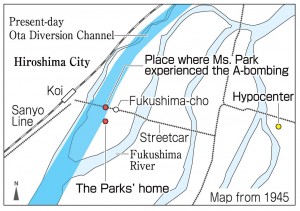

“The city of Hiroshima disappeared in an instant. What happened here was so much more than a disaster,” said Park Namjoo, 82, a South Korean resident of Japan who experienced the atomic bombing near her home in the Fukushima-cho district (now part of Nishi Ward), about 1.9 kilometers from the hypocenter. Because recalling her memories brought back such sorrow, she avoided talking about her experience until around 10 years ago. But Ms. Park finally resolved to convey the horror of the atomic bombing in the hope that this tragedy, which has been seared into her mind, will never be repeated.

Back then, Ms. Park was a first-year student at Shintoku Girls’ High School (now located in Minami Ward). She was the eldest daughter among six siblings. At that time her name was “Namiko Arai.” On the Korean Peninsula, which was under Japan’s colonial rule, many Koreans took on Japanese names to abide by an edict issued by the Japanese authorities.

On August 6, the first-year students at Ms. Park’s school did not have to attend. Instead, she was taking a younger brother and sister to a relative living in the city of Hatsukaichi, where that relative had evacuated earlier. Shortly after the three children boarded the streetcar at the Fukushima stop, Ms. Park heard the buzz of a U.S. B-29 bomber. The next moment, there was a bright flash in front of her eyes and the streetcar was assailed by a huge ball of fire and an enormous roar. Ms. Park and her siblings frantically fled the streetcar and found that their surroundings now seemed to be shrouded in fog, a result of dust choking the air. She was bleeding from her head, but felt no pain.

The family home in Fukushima-cho was destroyed by the blast, so they were forced to stay outdoors, at the bank of a river, for several days. During this time, scores of bodies were cremated nearby at sites on the river bank. Maggots began to fester in people’s wounds, and their bodies started to swell up. “There was no human dignity in the deaths caused by the atomic bombing,” Ms. Park said.

At the time, there was a large population of Koreans in Hiroshima. Her late father, Jaegyeong, was originally from Gyeongsangnam-do in South Korea and had crossed the sea to Hiroshima around 1929 for work. Ms. Park was then born in Hiroshima and educated in the militaristic spirit of the day. She said, “I thought Japan was a divine nation. I believed, from the bottom of my heart, that Japan would never be defeated in the war.”

Nine days after the bombing, Ms. Park learned that Japan had surrendered when she overheard the emperor’s radio address from a house nearby. She was indignant and wept, but her father said evenly, “This is liberation.” Her father, a quiet man, had revealed his true feelings.

After the war, Koreans in their neighborhood began returning to their homeland. But Ms. Park’s family chose to remain in Hiroshima and they searched for her uncle, who went missing in the bombing. The family huddled together in a shack and sold steamed potatoes in the “black market” that sprang up outdoors. Her father earned meager wages from doing manual labor.

Because she was Korean, she suffered discrimination. The postwar period was a time of hardship, but she said she was able to survive because “The teachers and other people around me were kind and lent us their support. We were helped by the kindness of many people.” When she was 19, she got married to a man six years her senior and they had four children.

Her husband passed away in 2002. Around that time, she began assisting A-bomb survivors living in South Korea who were trying to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate, issued by the Japanese government. These survivors who went back to the Korean Peninsula have suffered various hardships since their return. One day, 13 years ago, she was walking through the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, in Naka Ward, when students on a school trip to the city spoke to her. She then told them about the conditions in Hiroshima in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. Encouraged by this encounter, she began to feel a stronger desire to share her experiences with younger generations. “There is no difference in the hardships experienced by A-bomb survivors, whether they’re from Japan or from South Korea,” she said. “Nuclear weapons and war are completely unacceptable.” She expressed her determination to continue conveying her account as much as she can.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Willingness of young people to listen is important

Ms. Park said that she couldn’t tell anyone about what she witnessed that day, because it was so horrifying. But she changed her way of thinking after some elementary school students, on a school trip, talked to her 13 years ago. I saw that the attitude of young people, in showing a willingness to listen to the experiences of the A-bomb survivors, is important. I, too, am determined to listen to the accounts of A-bomb survivors and convey their experiences to the people around me by writing articles. (Tokitsuna Kagagishi, 14)

Can’t imagine everything “for the sake of the nation”

Ms. Park said that, as she was born in Japan, she believed that Japan would win the war because it was a “divine nation.” I can’t imagine conditions like this, where people’s lives and ideas were so influenced by the war and all aspects of daily life were pursued for the sake of the nation. And, in the end, many Koreans also lost their lives in the atomic bombing. I felt that people who have responsibility for the future of society must pay careful attention to the conditions of their time. (Chiaki Yamada, 15)

Peace comes from being thoughtful toward others

Ms. Park said, “Peace means being thoughtful toward other people.” Her family, which didn’t return to South Korea, were able to endure with the support of many people. I think it’s important never to discriminate against others and for people to treat one another with kindness. I want to help preserve the peace we enjoy today, which has been built on the many lives that were lost and the sorrows suffered by the survivors. (Mei Morimoto, 17)

(Originally published on August 31, 2015)