Tokie Matsumoto, 86, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima

Oct. 5, 2015

Experienced A-bombing without the flash and boom

by Hisashi Kawate, Staff Writer

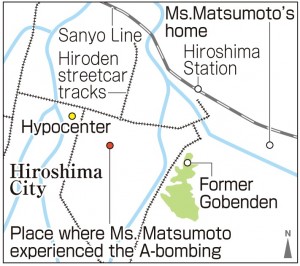

Tokie Matsumoto (née Uehara), 86, was in Mikawa-cho (now part of Naka Ward), about 800 meters from the hypocenter when the atomic bomb exploded on August 6, 1945. As the sound of a B-29 bomber grew louder, she glanced up at the sky, and at that moment everything went black. She was knocked to the ground as if struck by something from behind. “I had no idea what was happening,” she said. “I didn’t experience the flash and boom of the bomb.”

At the time, Ms. Matsumoto was a 15-year-old student nurse. On the morning of August 6, she left the hospital in Sakai-machi (now part of Naka Ward), where she lived as an emergency nurse, and went to nearby Mikawa-cho to help clear away demolished homes to create a fire lane. In the bag over her shoulder, she had only some mercurochrome, bandages, and two pairs of tweezers. She was standing in the second row of five rows, holding a Red Cross flag and listening to the precautions issued by the leader of a neighborhood association, when the atomic bomb detonated.

After the blast, she gradually was able to make sense of her surroundings, and saw that the stone wall behind them had collapsed onto those who were standing in the third to fifth rows. Ms. Matsumoto’s lower body was also pinned by the stone rubble, but she suffered only scratches to her arms, and no burns, partly because the wall may have shielded her from the bomb’s thermal rays.

She was desperate to flee and managed to struggle out of the rubble. Her white pants were muddied with the blood and flesh of others who had been crushed by the wall. She pitched in to pull out survivors still pinned down. Because her shoes had disappeared, she put on the shoes of a victim and then ran from the scene with other people as spreading flames approached.

She had nowhere to go and didn’t know where she was heading. Eventually, she found herself at Gobenden, a place she recognized on Hijiyama Hill. There, she saw people whose skin was peeling away from their bodies or had collapsed to the ground in their burnt clothing. One man was groaning, his feet mangled. She wanted to help them, but there was nothing she could do.

Ms. Matsumoto crossed over Hijiyama Hill and returned to her home in Minamikaniya-cho (now part of Minami Ward), where she was reunited with her parents. She was uncertain how much time had passed since the bombing took place. She cried and screamed, “I’ve left everyone behind!”

Part of her house was also destroyed, with the roof blown in the blast. Since her family could not stay there, they carried her through the night on a two-wheel cart to her grandparents’ home (the parents of her mother, Miyano) in the village of Tomo. They settled in a storehouse with earthen walls. For the next month, Ms. Matsumoto remained only semi-conscious and all her hair fell out. Her mother later told her that her sister, Kazuko, who was six years younger, had returned from an evacuation site in the countryside and asked her mother, “Who is that?” because Ms. Matsumoto was nearly unrecognizable.

After the war, Ms. Matsumoto resumed working as a nurse. During this time she witnessed discrimination against A-bomb survivors, hearing such comments as “They won’t be able to give birth to healthy children” and “They’ll develop cancer or leukemia.” After she got married and became pregnant, she suffered a miscarriage. When a relative said, “Maybe it was because of the atomic bombing,” she was distressed. Nevertheless, she went on to have two children, and now has four grandchildren and one great-grandchild. “If you think positively, it will somehow turn out well,” she said. “I’ve decided not to brood over things.” She was able to overcome the discrimination she encountered with the positive attitude she had acquired from her experience as a nurse.

For many years she avoided talking about her experience of the atomic bombing because these were memories she didn’t want to recall. But when she developed breast cancer at the age of 71, she wrote a memoir and shared it with her siblings and her children.

Even today, 70 years after the atomic bombing, her memories of that day haven’t faded. “I hate war,” she said. “It turns happy lives upside down.” This year she rewrote her memoir, the fourth revision. She concluded the text by writing, “When I watch scenes of war on TV, it feels like World War II happened just yesterday. I want us all to shout to the sky, ‘Never fight another war.’”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Surprised by the account of a survivor near the hypocenter

Ms. Matsumoto was closer to the hypocenter than any A-bomb survivor I’ve talked to. She didn’t experience the flash and boom at the time of the atomic bombing. This surprised me because all the accounts I had heard included mention of the flash and then the boom that followed. We must not wage war. I want to continue conveying the message that war must never be condoned by gathering information and writing articles. (Hiroyuki Hanaoka, 13)

Sensing her strength as a nurse

Though Ms. Matsumoto’s hair fell out because of radiation-related illness, she returned to working as a nurse to help save people’s lives. I sensed her great strength. I was happy to hear that she decided to talk about her experience because she’s interested in what young people today are thinking. I plan to be more proactive about listening to the accounts of A-bomb survivors and sharing them with other people. (Haruka Shinmoto, 16)

Keywords

Gobenden

Gobenden was a rest house for the emperor when the Imperial Diet gathered in the city of Hiroshima during the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895). It was located on the grounds of Hiroshima Castle, along with the Imperial Headquarters, but was sold to the city in 1895 and moved to Hijiyama Hill in 1909. It was incinerated in the atomic bombing.

(Originally published on September 21, 2015)