Messages from A-bomb Survivors: Sunao Kanezaki, Part 2

Dec. 7, 2010

Sunao Kanezaki, 84, Fukushima-cho, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Part 2: Why didn’t I respond to that girl’s plea?

Note: This series first appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun in 2001.

Leaving the girl with her heartache

There’s one scene from that day that I can’t forget. I was worried about my wife and my two children, so I hurried from my workplace in Hatsukaichi to Fukushima-cho [in present-day Nishi Ward], where we were living at the time. I looked for them everywhere, but I couldn’t find them. While scouring the town, a girl spoke to me from the edge of the Yamate River [now the Ota River Canal]. She was burned black, and there were bodies around her, their arms sticking in the air.

The girl was lying among the weeds. She said, “Mister, I’m from Iwakuni. My father and mother must be waiting anxiously for me to come home. Please help me.”

Mr. Kanezaki’s wife was pregnant and his children were four and two. Though their house was badly damaged, they were able to flee safely to the suburbs.

I had to tear myself away from the girl. But why couldn’t I have helped her move even one or two steps toward Iwakuni, though she might have died on my back? It’s been more than 50 years, but I still can’t forget. Why didn’t I respond to her plea?

I still feel guilty. She was calling desperately for help. Her face was burned, her hair was scorched and frizzy--only her eyes were left unharmed. I guess I’ll have to carry this feeling of guilt to my grave.

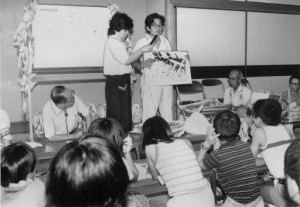

In 1981, Mr. Kanezaki began to share his account of the bombing shortly after quitting his job at a hospital. He created a picture-story show entitled “Ten-ni Yakareru” (“Burned by the Heavens”) which included the episode with the girl he encountered. He presented this story to students on school trips. Later, the story was turned into an animated film.

Putting victims’ anguish into a monument

Nearly 30 years ago, we decided to build a monument to the A-bomb victims in the Fukushima district. We wanted to make something tangible which would represent the anguish of those who died without the chance to fulfill their dreams. When I went around the community, seeking support for the project, some people suggested that the monument be for the dead soldiers as well.

But this monument for the A-bomb victims has a special significance: it’s an appeal for the tragedy to never be repeated. This is about the survival of the human race. If others were included, it would dilute the meaning of the monument. This is how I explained it.

The monument for the atomic bomb victims was unveiled in July 1976. Inscribed are the words: “Among bodies with both arms extended into the air, as if holding the sky, there were some still alive.”

The A-bomb survivors, while wishing for the world to be free of nuclear weapons one day, are now dying one after another. In not many more years, they will all be gone. We have to move swiftly and hand over this wish for nuclear abolition to the next generation.

After the ban-the-bomb movement split into factions in 1963, the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations also became divided. I urged people to unite and act together despite their differences of opinion, because we shared a common goal. But I was unable to persuade them. Once there were these divisions, the movement lost its momentum. It was awful. Without unity, we can never have significant power. This is my message.

(Originally published on July 20, 2001)

Part 2: Why didn’t I respond to that girl’s plea?

Note: This series first appeared in the Chugoku Shimbun in 2001.

Leaving the girl with her heartache

There’s one scene from that day that I can’t forget. I was worried about my wife and my two children, so I hurried from my workplace in Hatsukaichi to Fukushima-cho [in present-day Nishi Ward], where we were living at the time. I looked for them everywhere, but I couldn’t find them. While scouring the town, a girl spoke to me from the edge of the Yamate River [now the Ota River Canal]. She was burned black, and there were bodies around her, their arms sticking in the air.

The girl was lying among the weeds. She said, “Mister, I’m from Iwakuni. My father and mother must be waiting anxiously for me to come home. Please help me.”

Mr. Kanezaki’s wife was pregnant and his children were four and two. Though their house was badly damaged, they were able to flee safely to the suburbs.

I had to tear myself away from the girl. But why couldn’t I have helped her move even one or two steps toward Iwakuni, though she might have died on my back? It’s been more than 50 years, but I still can’t forget. Why didn’t I respond to her plea?

I still feel guilty. She was calling desperately for help. Her face was burned, her hair was scorched and frizzy--only her eyes were left unharmed. I guess I’ll have to carry this feeling of guilt to my grave.

In 1981, Mr. Kanezaki began to share his account of the bombing shortly after quitting his job at a hospital. He created a picture-story show entitled “Ten-ni Yakareru” (“Burned by the Heavens”) which included the episode with the girl he encountered. He presented this story to students on school trips. Later, the story was turned into an animated film.

Putting victims’ anguish into a monument

Nearly 30 years ago, we decided to build a monument to the A-bomb victims in the Fukushima district. We wanted to make something tangible which would represent the anguish of those who died without the chance to fulfill their dreams. When I went around the community, seeking support for the project, some people suggested that the monument be for the dead soldiers as well.

But this monument for the A-bomb victims has a special significance: it’s an appeal for the tragedy to never be repeated. This is about the survival of the human race. If others were included, it would dilute the meaning of the monument. This is how I explained it.

The monument for the atomic bomb victims was unveiled in July 1976. Inscribed are the words: “Among bodies with both arms extended into the air, as if holding the sky, there were some still alive.”

The A-bomb survivors, while wishing for the world to be free of nuclear weapons one day, are now dying one after another. In not many more years, they will all be gone. We have to move swiftly and hand over this wish for nuclear abolition to the next generation.

After the ban-the-bomb movement split into factions in 1963, the Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations also became divided. I urged people to unite and act together despite their differences of opinion, because we shared a common goal. But I was unable to persuade them. Once there were these divisions, the movement lost its momentum. It was awful. Without unity, we can never have significant power. This is my message.

(Originally published on July 20, 2001)