Yoshiko Kajimoto, 84, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Nov. 2, 2015

Handing down the crime of the atomic bombing without bitterness

by Taiki Yomura, Staff Writer

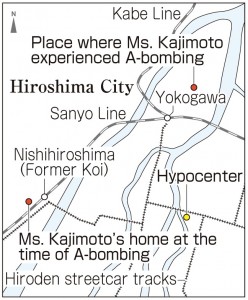

“I thought the earth had exploded,” said Yoshiko Kajimoto (née Kimura), recalling the blast of the atomic bomb. “The land in front of me bulged up, and I was pushed upward for a moment by the strong winds from the explosion.” Back then she was 14 years old, a third-year student at Yasuda Girls’ High School (now Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School and High School). Like many students, she had been mobilized to work for the war effort and was helping produce propeller parts for aircraft in a factory located in Misasa-machi (now part of Nishi Ward), about 2.3 kilometers north of the hypocenter.

There was a flash of deep blue light on the window. She thought that the factory had been hit directly by a bomb, and she would be killed. The faces of family members flashed in her mind as she scrambled under a machine, then passed out.

She came to at the sound of a friend’s voice crying for help and found herself pinned under the wreckage of the two-story wooden building. She could only move her head and her hands. Her friend, pinned beneath her, emerged after writhing desperately, and Ms. Kajimoto managed to struggle out of the rubble, too. Her right arm was pierced with fragments of glass and the skin on her shin was flayed when she pulled out her right leg.

Her surroundings were dead silent. Though it was morning, darkness had descended and in the air was a smell like red dirt and rotten fish. Ms. Kajimoto and her friends headed north, carrying classmates on stretchers. Her bare feet hurt.

Along the way, they saw many people with severe burns and others who had died lying under trees in Oshiba Park (now part of Nishi Ward). Seeing fires rising in the city, Mr. Kajimoto and her friends spent that night on a river bank. “What has become of our homes?” they wondered and wept.

The following day, they stayed at someone’s home. The day after that, they were given rice balls from residents in Yasu Village (now part of Asaminami Ward). The rice balls were the first thing she ate since the atomic bombing.

She then set out for her home in the Koi district (now part of Nishi Ward). En route, she was reunited with her father, who was searching for her. Her father took out small white rice balls, made by her mother. Her mother had told her father, “If you find Yoshiko, let her eat them before she dies.” She restrained herself from eating the rice balls until she got home, then shared them with her brothers.

After the war, Ms. Kajimoto suffered a number of hardships. Her father, who experienced the atomic bombing at their home, about 2.5 kilometers from the hypocenter, died suddenly 18 months after the attack, despite escaping injury at the time. Her mother was hospitalized repeatedly. Ms. Kajimoto thought, “I have to do something, or my family will die,” and she worked feverishly at a relative’s clothing shop to provide for her three brothers and pay her mother’s hospital bills.

She wonders how long the atomic bombing will haunt her life. She got married in 1957, and now has two daughters, four grandchildren, and one great-grandchild, but she worries about the bomb’s aftereffects. Fifteen years ago, two-thirds of her stomach was removed because of cancer. To think that the atomic bombing has also brought illness upon her children breaks her heart. “The crime of the atomic bombing is its lingering effect on children and grandchildren,” she said.

Today, Ms. Kajimoto shares her experience around 130 times a year, particularly to students visiting Hiroshima on school trips. In 2000, her granddaughter, who was a third-year student in junior high school at the time, suggested that she start telling her story, and she began to do so in the spring of 2001. Until that point, she had wondered why her memories continued to dwell in her mind, despite trying to hide from them and forget them. Now she says, “I hope the same mistake will never be repeated. I want to share my experience with as many people as possible.” Toward that end, she has traveled to the United States and Spain.

The many impressions she receives have touched her heart. One child who was suicidal grew more positive after hearing her speak, and some students are moved to seek paths as peace builders. When a high school student from the United States told her, “I’m sorry,” she thought that children shouldn’t feel obligated to apologize. Ms. Kajimoto believes that she wouldn’t have matured if she had continued to feel bitter toward the United States and that the cycle of revenge and war cannot be broken if people are unable to find some forgiveness. She says she no longer feels any hatred toward the United States.

Ms. Kajimoto is sharing her experience with the “memory keepers” of the A-bomb experiences, citizens who are undergoing training organized by the City of Hiroshima to hand down A-bomb accounts to younger generations. Her second daughter, 54, is now taking part in this training and a grandchild is also interested in doing so. “I’m happy that they will convey my spirit,” Ms. Kajimoto said.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Never repeat this tragedy

Ms. Kajimoto said, “I want you to listen to the A-bomb accounts not merely as someone else’s business, but as your own personal business, too.” I think she’s worried that this tragedy will be repeated if the atomic bombing is forgotten. Even now, 70 years since the end of World War II, the atomic bombing continues to cause suffering. I want to convey her message, “Never repeat this mistake,” to as many people as possible. (Kotoori Kawagishi, 13)

Importance of living a humble, happy life

Ms. Kajimoto said, “The ten years after the war were hell.” She supported her family without doing what she wanted to do, and even thought of killing herself. What I do to help my family is completely different from what she did for hers. When I return home after school, my mother has prepared a hot meal for me. I keenly feel the importance of living a humble, happy life. (Riho Kito, 14)

Sharing her experience with others

I was struck by the fact that Ms. Kajimoto had to start supporting her family right after she graduated from high school, following her father’s death. War is merciless in the way it affects children’s lives, too. Ms. Kajimoto faced terrible hardship, working from morning to night and she didn’t even have enough time to talk to her friends. Back then she was nearly the same age as I am now. But I have the support of my family; I can’t imagine having to work. I want to share her experience with my friends. (Harumi Okada, 16)

(Originally published on October 19, 2015)