Kazue Kusada, 85, Kaita, Hiroshima Prefecture

Jan. 12, 2016

Fragment of glass was lodged in her back for 42 years

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

At the age of 15, Kazue Kusada (née Komatsu), 85, experienced the flash of the atomic bomb and was badly burned. After the war, she was able to forget her harrowing memories and regain her youth when she devoted herself to playing softball at Yasuda Girls’ High School (now Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School and High School). Today, people can lead the lives they wish. Ms. Kusada hopes that war will never be waged again.

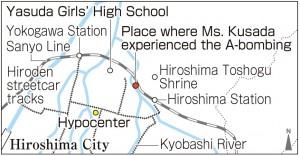

On August 6, the day of the bombing, Ms. Kusada was a fourth-year student and was at a schoolmate’s house (about two kilometers from the hypocenter) in the Osuga district (now part of Minami Ward). While waiting with another schoolmate on the second floor, so they could walk to school together, she heard the sound of a train on the Sanyo Line blowing its whistle repeatedly. As they were wondering aloud about the train, a flash of yellow light struck the left side of her face.

She did not hear an explosion, but became trapped under the collapsing ceiling. She was rescued from the wreckage, having suffered terrible burns to the lower part of her body. Her pair of monpe, traditional Japanese work pants, had burned away, leaving only the rubber of the hems behind. But she felt no pain at all. She could not comprehend what had happened.

When she went to the nearby Kyobashi River, she saw people swimming or floating. The banks were jammed with soldiers that had swollen faces. As she was fleeing to Hiroshima Toshogu Shrine (now in Higashi Ward) with her schoolmates, there was a mother holding a baby. Both of them were dead, but no one showed the slightest concern.

Around noon on the following day, she was brought to her home by a man who came from the Yano district (now part of Aki Ward) to help the victims. The man, who called himself “Komatsu,” the same as her maiden name, put her on a bicycle and walked it about ten kilometers. She regrets not properly expressing her gratitude to him.

At home, Ms. Kusada was bedridden, but her mother covered her wounds with gauze soaked in cucumber juice. That October she was able to sit up. She then slowly stood, holding onto a pillar, but blood oozed from her wounds. After that, she was able to return to school, but the scars from her burns became keloids.

She was introduced to softball the year after the atomic bombing. A teacher, Minoru Yasuda (who later became president of Yasuda Girls’ High School), recommended that she play “ground ball,” or softball. She thought that softball was played only by boys, so at first she declined. But once she tried it, she found it fun, and immersed herself in the game.

Ms. Kusada became the team captain. Early on, one player, not knowing the rules of softball, swung the bat and ran to third base; another player made a hit but the base runner did not advance to the next base. The players lacked softball equipment, so they played with their bare hands and in bare feet, but the game helped release them from their horrific memories by moving their bodies and working together. They trained hard in practices and won the first championship in the Hiroshima prefectural tournament in 1947.

Ms. Kusada also enjoys watching baseball games. She would often go to the professional baseball games of the Hiroshima Toyo Carp with her husband, Shizuo, who died in 1990 at the age of 72. She was excited to watch the late Ryohei Hasegawa, a “small but great pitcher,” pitch twice in one day.

She still sometimes thinks back to the atomic bombing, though. When she went on a trip to a hot spring with some friends, she regretted going with them, thinking, “Oh, dear. They’ll see my keloids.” In 1987, when she underwent surgery because of a sore back, a fragment of glass, about two centimeters long, was removed from her body. It had lodged there in the blast of the atomic bomb.

Last September, Ms. Kusada served as “the oldest home run girl of all time” at Mazda Zoom-Zoom Stadium (in Minami Ward). Men and women of all ages, wearing Carp jerseys, come to the stadium to cheer for the Carp, a dream-like atmosphere for her. “War must never be waged again,” she said. “I want nations and people to create a peaceful world through dialogue, without fighting. I hope we can all continue to live healthy and happy lives.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Suffered wounds and burns at a young age

Ms. Kusada had a piece of glass that was about two centimeters removed from her back. She said that other fragments of glass might still be lodged in her body. I was surprised that she experienced the bomb’s massive blast, and the fact that she suffered such serious wounds and burns at a young age broke my heart. She said, “I hope everyone will solve their problems through dialogue, without fighting.” I feel her hope deeply. (Kotoori Kawagishi, 13)

Hardships that transcend time

Ms. Kusada said that she did not want to get into a spa with other people because she had keloids on her legs. I fell down in a race, and a scar on my shoulder became a keloid. The cause and degree of my keloid are different from Ms. Kusada’s scars, suffered in the war, but I also don’t want others to see my keloid. Such psychological and physical scars are hardships that transcend time. War, and the suffering it brings to both sides, must not be repeated. (Riho Kito, 14)

Grateful to enjoy playing softball

I was shocked to hear that Ms. Kusada began playing softball without any gloves or spikes. I wonder how she caught the ball. But it was the beginning of postwar women’s softball. I also play on a softball team and we have adequate equipment. I realized that we can enjoy playing softball because many people arranged for us to play it. I want to express my gratitude to them. (Nanaho Yamamoto, 16)

(Originally published on December 15, 2015)