A-bombed cities seek voice in new U.S. national historical park for the Manhattan Project

Feb. 3, 2016

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Last November, the U.S. government designated several remaining sites of the Manhattan Project as a national historical park. The Manhattan Project is the name of the massive effort that produced the atomic bombs used in World War II. Among the American public, the idea that the A-bomb attacks ended the war is deeply rooted. How, then, will the new national park sites convey the voices of the A-bomb victims and survivors? Amid these concerns, plans to develop these sites have begun.

In this connection, the U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees the country’s national parks, held a closed forum with experts in Washington, D.C. Along with 19 experts, including historians from the United States, the organizers invited Yasuyoshi Komizo, the chairperson of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, located in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, and Masao Tomonaga, the honorary director of the Japanese Red Cross Nagasaki Genbaku Hospital, located in Nagasaki, to take part.

The participants discussed the development of the atomic bombs from a variety of perspectives, including science, technology, and politics, to establish an orientation for the park and select elements for inclusion. This discussion will be referenced for the continuing development of the park.

Link with positive perception

Mr. Tomonaga urged that such issues as the inhumane consequences of the atomic bombs and their long-term effects on human health be incorporated. Mr. Komizo spoke on behalf of A-bomb survivors who seek the abolition of nuclear weapons, stressing that the survivors “don’t hold a vengeful spirit.” He went on to say, “I hope these places will become venues to advance a secure and humane world that does not rely on such brutal weapons.”

Mr. Komizo said, “A variety of people took part, with the organizers wanting the voices of the A-bombed cities to be heard. This position was a step forward for us.” At the same time, he found it necessary to repeatedly press his points to the U.S. side. “The focus of the discussion tended toward the question of why the United States was alone in successfully developing atomic bombs, though both Germany and Japan had also sought these weapons,” he said.

For the United States, the development of the atomic bomb serves as a milestone of that nation’s science and technology. Mr. Tomonaga said, “I didn’t hear explicit statements that these places should convey a glorious history that brought victory in the war against Japan. But there were views which implied pride in U.S. science and technology.” Such praise of science could thus be linked with a positive perception of the use of the atomic bombs.

Emphasize “fairness”

This year the National Park Service, under the U.S. Department of the Interior, will compile a “foundation document” that will identify the basic understanding of the park’s values and history. The National Park Service will reportedly seek opinions from the public, too.

The 1990s was a time of fierce debate over the atomic bombs. The Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum had planned an exhibition featuring the fuselage of the B-29 bomber “Enola Gay,” the plane that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The museum sought to also display artifacts left behind by A-bomb victims, but U.S. veterans of the Pacific War and others were vehemently opposed. Ultimately, the original plan was scrapped and artifacts left behind by A-bomb victims were not displayed.

Theoretically, the national historical parks in the United States also seek to convey negative events of the past, such as the mistreatment of indigenous peoples, slavery, and the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. But there is a thin line between this intention and the patriotic idea that the nation bears a debt to those who sacrificed themselves for the sake of the country. It is therefore vital to make efforts over the next few years to support the view of the A-bombed cities.

Toshihiro Higuchi, an assistant professor of the history of science at Georgetown University, is familiar with the past when it comes to relations between Japan and the United States involving nuclear issues. “Conservatives and their views will put pressure on the orientation of the park, that can’t be helped,” Mr. Higuchi said. “The question is, what materials will be presented at venues where visitors engage with a variety of perspectives and reflect on their own. And so Hiroshima and Nagasaki must continue to convey their point of view. It is important, too, to emphasize ‘fairness,’ a principle of democracy and an American ideal.”

Keywords

The Manhattan Project National Historical Park

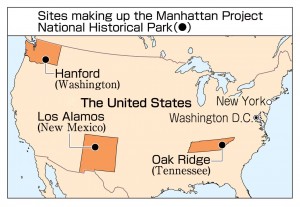

The Manhattan Project was the U.S. effort to develop the atomic bombs during World War II. Facilities involved in the project and their environs, in three locations, were designated a national historical park on November 10 of last year. These locations include Los Alamos, New Mexico, the base of operations; Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where the highly enriched uranium for the Hiroshima A-bomb was produced; and Hanford, Washington, where the plutonium for the Nagasaki A-bomb was produced. Sally Jewell, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, has said that her department will be impartial in its development of the park, giving due consideration to the A-bombed cities. At the same time, expectations are high for promoting tourism at the park.

(Originally published on January 11, 2016)

Last November, the U.S. government designated several remaining sites of the Manhattan Project as a national historical park. The Manhattan Project is the name of the massive effort that produced the atomic bombs used in World War II. Among the American public, the idea that the A-bomb attacks ended the war is deeply rooted. How, then, will the new national park sites convey the voices of the A-bomb victims and survivors? Amid these concerns, plans to develop these sites have begun.

In this connection, the U.S. Department of the Interior, which oversees the country’s national parks, held a closed forum with experts in Washington, D.C. Along with 19 experts, including historians from the United States, the organizers invited Yasuyoshi Komizo, the chairperson of the Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation, located in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, and Masao Tomonaga, the honorary director of the Japanese Red Cross Nagasaki Genbaku Hospital, located in Nagasaki, to take part.

The participants discussed the development of the atomic bombs from a variety of perspectives, including science, technology, and politics, to establish an orientation for the park and select elements for inclusion. This discussion will be referenced for the continuing development of the park.

Link with positive perception

Mr. Tomonaga urged that such issues as the inhumane consequences of the atomic bombs and their long-term effects on human health be incorporated. Mr. Komizo spoke on behalf of A-bomb survivors who seek the abolition of nuclear weapons, stressing that the survivors “don’t hold a vengeful spirit.” He went on to say, “I hope these places will become venues to advance a secure and humane world that does not rely on such brutal weapons.”

Mr. Komizo said, “A variety of people took part, with the organizers wanting the voices of the A-bombed cities to be heard. This position was a step forward for us.” At the same time, he found it necessary to repeatedly press his points to the U.S. side. “The focus of the discussion tended toward the question of why the United States was alone in successfully developing atomic bombs, though both Germany and Japan had also sought these weapons,” he said.

For the United States, the development of the atomic bomb serves as a milestone of that nation’s science and technology. Mr. Tomonaga said, “I didn’t hear explicit statements that these places should convey a glorious history that brought victory in the war against Japan. But there were views which implied pride in U.S. science and technology.” Such praise of science could thus be linked with a positive perception of the use of the atomic bombs.

Emphasize “fairness”

This year the National Park Service, under the U.S. Department of the Interior, will compile a “foundation document” that will identify the basic understanding of the park’s values and history. The National Park Service will reportedly seek opinions from the public, too.

The 1990s was a time of fierce debate over the atomic bombs. The Smithsonian Institution’s National Air and Space Museum had planned an exhibition featuring the fuselage of the B-29 bomber “Enola Gay,” the plane that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima. The museum sought to also display artifacts left behind by A-bomb victims, but U.S. veterans of the Pacific War and others were vehemently opposed. Ultimately, the original plan was scrapped and artifacts left behind by A-bomb victims were not displayed.

Theoretically, the national historical parks in the United States also seek to convey negative events of the past, such as the mistreatment of indigenous peoples, slavery, and the internment of Japanese-Americans during World War II. But there is a thin line between this intention and the patriotic idea that the nation bears a debt to those who sacrificed themselves for the sake of the country. It is therefore vital to make efforts over the next few years to support the view of the A-bombed cities.

Toshihiro Higuchi, an assistant professor of the history of science at Georgetown University, is familiar with the past when it comes to relations between Japan and the United States involving nuclear issues. “Conservatives and their views will put pressure on the orientation of the park, that can’t be helped,” Mr. Higuchi said. “The question is, what materials will be presented at venues where visitors engage with a variety of perspectives and reflect on their own. And so Hiroshima and Nagasaki must continue to convey their point of view. It is important, too, to emphasize ‘fairness,’ a principle of democracy and an American ideal.”

Keywords

The Manhattan Project National Historical Park

The Manhattan Project was the U.S. effort to develop the atomic bombs during World War II. Facilities involved in the project and their environs, in three locations, were designated a national historical park on November 10 of last year. These locations include Los Alamos, New Mexico, the base of operations; Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where the highly enriched uranium for the Hiroshima A-bomb was produced; and Hanford, Washington, where the plutonium for the Nagasaki A-bomb was produced. Sally Jewell, the U.S. Secretary of the Interior, has said that her department will be impartial in its development of the park, giving due consideration to the A-bombed cities. At the same time, expectations are high for promoting tourism at the park.

(Originally published on January 11, 2016)