Gray area: Effects of exposure to low-level radiation, Part 1 [1]

Mar. 3, 2016

Fukushima after five years: Time stands still in contaminated town

by Jumpei Fujimura, Staff Writer

Beyond the fallen gate of Kumamachi Elementary School, the schoolyard is now overrun with pampas grass and young pine trees. Kumamachi Elementary School is located in the town of Okuma, about 3.7 kilometers southeast of the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant in Fukushima Prefecture. “Just five years ago, it was covered with lovely grass,” murmured Kiyoe Kamata, 73, through his mask as he escorted me around the area. Before the Great East Japan Earthquake of March 2011, Mr. Kamata ran a fruit farm nearby.

“March 11”

Peering into a classroom, I found “March 11” written on the blackboard and the clock still pointing at 2:48 p.m., immediately after the earthquake struck. The students apparently evacuated in a hurry because many backpacks were left behind on the desks and floor. Both the desolate schoolyard and the school building, now frozen in time, are emblematic of the untouched “difficult-to-return” zone.

When I looked at my dosimeter, it showed a radiation level of 6 microsieverts per hour. When I lowered it to the ground, the indicator instantly jumped to 15 microsieverts. This demonstrates how radioactive cesium, which was released as a result of the nuclear accident, has remained near the surface of the land. If I stayed here for a full year, I would receive a total radiation dose of 131 millisieverts. According to the United Nations Scientific Committee, an amount in excess of 100 millisieverts can raise the risk of developing cancer.

“The level of radiation has dropped a lot compared to the time of the accident,” Mr. Kamata said. “But getting used to this situation has produced a surprising effect.” He went on to explain that in the summer of 2011, when he returned to the town for the first time following the accident, the level of radiation around his house was more than 100 microsieverts per hour. As the local residents moved around the area via a bus provided by the Japanese government, all of them were very nervous and rushed into their homes from the bus parked nearby. They came back, out of breath, carrying out personal belongings.

Now, however, some residents enter the same area without donning the radiation protection suit recommended by the government. “If we don’t measure the level of radiation, we don’t know if it really exists,” he said. “That’s why it’s so frightening, but, at the same time, it makes us feel numb to the danger.” Mr. Kamata’s words reflect the sentiments of those who must contend with the contaminated conditions of radiation exposure.

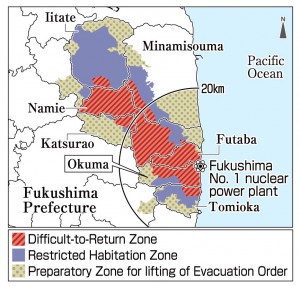

96% of the town designated a “difficult-to-Return” Zone

Since 96% of the residential areas of town have been designated a “difficult-to-return” zone, around 11,000 Okuma citizens are still living elsewhere as evacuees. To date, Mr. Kamata has moved five times and now lives with his wife, 66, and his mother, 97, in the city of Sukagawa. He dares to make the two-hour drive to his hometown because of his art activities involving “frottage,” where he creates pictures by placing a piece of paper on the town’s stone monuments and other objects, which are becoming buried by dust and dirt, then rubbing over the paper with chalk.

He is unsure, though, how long he can keep up these efforts. The area where Mr. Kamata’s home and Kumamachi Elementary School are located is the planned construction site for an intermediate storage facility that will hold decontamination waste from Fukushima Prefecture for the next 30 years. The trial transporting of this waste has already been under way for about a year. While negotiations to purchase the site have not gone well, the central government is expected to begin construction work on some of the facilities in October.

The town of Okuma is planning to build residential homes and other facilities outside the “difficult-to-return” zone by 2018. Mr. Kamata said, “I can never get back the life I used to have before the earthquake. Even if the government keeps the name of the town alive, it will be a different place, where people involved in the decommissioning of the plant live.” Mr. Kamata is reconciled to the fate of the hometown he loves.

When people are exposed to low-level radiation, how is their health affected? Science is currently unable to provide a clear answer to this question. The fifth anniversary of the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant will soon arrive. My steps took me through the contaminated Fukushima landscape, where people must still contend with the threats posed by unseen radiation.

Keywords

Difficult-to-Return Zone

Among the three zones where the evacuation from the Japanese government is still in place, the Difficult-to-Return Zone is an area where 50 millisieverts or more of annual radiation exposure has been observed. In principle, this zone is off-limits, but residents from the area are permitted to enter 30 times per year if they request a visit in advance. The maximum length of time per visit is five hours. Including the town of Okuma, this zone covers a total of seven towns and villages, among them the towns of Futaba and Namie.

(Originally published on March 3, 2016)