Gray area: Effects of exposure to low-level radiation, Part 2 [3]

Apr. 15, 2016

Workers in Fukushima: Hopes and challenges for scientific clarity based on medical exam results

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Since the 2011 nuclear accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), many workers have been involved in the work to decommission the reactors and conclude these troubled conditions. Among them, 20,000 workers who entered the site prior to December 16, 2011, and have since been engaged in emergency tasks, are part of the government’s long-term measures to monitor the health of nuclear power plant workers as well as subjects in epidemiological studies on the health effects of radiation exposure. The organization responsible for these epidemiological studies is the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), located in Minami Ward, Hiroshima, which has amassed experience from the health examinations undertaken with A-bomb survivors. The question is: To what extent can the health effects from exposure to low-level radiation, the so-called “gray area,” be clarified scientifically? Hopes and challenges lie ahead for this effort, which will take decades to complete.

RERF to make use of knowledge and findings obtained in A-bombed cities

One after another, male workers arrived at the Iwaki Yoshima community medical checkup facility in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture. This facility is one of 70 health institutions in Japan that are taking part in the “Epidemiological Studies Targeting Emergency Workers” at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

The medical checkups include a blood pressure check, blood sampling, and hearing and electrocardiograph tests. Yasunori Onishi, 44, a resident of Iwaki, said after his checkup that he agreed to undergo the tests because he would be able to receive an echocardiography (ultrasonic) examination of his thyroid gland, an organ that is vulnerable to radiation. Approximately three weeks after the nuclear accident, he was working as closely as 30 meters to Units 3 and 4. His role was to temporarily restore the power supply that had been lost as a consequence of the disaster. His work involved laying out electrical cables while keeping his distance from the wreckage. During this time, he was exposed to radiation of around 50 millisieverts. “It was turmoil,” he recalled, “and because my dosimeter wasn’t working properly, I may have actually been exposed to levels of radiation that were a little higher than the dosimeter readings.”

For nine months, between the time of the nuclear accident and December 16, 2011, the government raised the allowable exposure limit from 100 millisieverts to 250 millisieverts as part of its emergency measures. About 20,000 workers were assigned to dangerous work sites. Consequently, the radiation dose of 174 workers, including TEPCO employees, exceeded 100 millisieverts. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare designated all 20,000 personnel as “emergency workers,” and decided to make a database of their addresses and radiation doses to monitor their health and to use this data for an epidemiological study on the health effects from radiation. The Radiation Effects Research Foundation, which was commissioned to oversee the epidemiological study, moved forward in fiscal 2015 to fully implement the project.

As a result of its research involving A-bomb survivors, RERF has stated clearly that a relationship exists between radiation exposure and the incidence of cancer. However, can this conclusion be applied to gradual radiation exposure, as in the case of nuclear accidents, in the same way as instantaneous exposure, like in the atomic bombings? “It is our duty to make use of the knowledge that has accumulated in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and contribute to the research being undertaken for the nuclear power plant workers in Fukushima,” said Toshiteru Okubo, the former chairman of RERF, which is spearheading this research. On one wall of a room at RERF is a map of Japan that bears red dots indicating the addresses of all the emergency workers now scattered around the country. The data from the medical checkups for these people is being sent to RERF by the nation’s participating facilities.

For A-bomb survivors, RERF has been pursuing medical checkups as part of an “adult health study” and analyzes biological specimens from the subjects, including the blood samples that its collects. RERF’s know-how now serves as the basis for the epidemiological study of emergency workers in Fukushima. Compared to 70 years ago, when neither dosimeters nor correct name lists for the A-bomb survivors were available, the accuracy of the data compiled these days is quite high. Mr. Okubo believes that the health effects from exposure to low-level radiation of less than 100 millisieverts will eventually become clear.

Nevertheless, there are some challenges that have not been seen in research focused on A-bomb survivors, and both RERF and the medical examination facilities across Japan are struggling to address these issues.

Many nuclear power plant workers move from one plant to another around the country every few months, making it difficult to get information on their whereabouts or to arrange medical checkups a few months in advance. While travel expenses to the nearest medical examination facility are provided, emergency workers are concerned about compensation for lost wages if they take off a day to undergo this checkup. In addition, RERF has sent documents to the subjects of this research, asking them to cooperate with these examinations, but 8,000 workers, or 40% of the total, have not replied. As a result, RERF must remain tenacious in its efforts.

Haruhiko Tsukamoto, 55, an employee of one of TEPCO’s subcontractors, showed his understanding of the situation by saying that, because the Fukushima nuclear accident was an unprecedented disaster, he should cooperate by taking part in the health effects study. But he also pointed out that the company provides other regular checkups and many workers are reluctant to undergo multiple examinations.

In the past, RERF was criticized for its stance of not offering treatment for A-bomb survivors despite studying and examining them. It has taken a long time to obtain approval from the survivors so that the results of this research can be used to help prevent further victims of radiation. RERF’s efforts to gain the consent and confidence of the nuclear power plant workers have just begun.

Differing views expressed by Radiation Effects Association and International Agency for Research on Cancer

Epidemiological studies for nuclear power plant workers are also being conducted by the Radiation Effects Association (REA) in Chiyoda Ward, Tokyo. As part of a project to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy, REA pursues research on the health effects of radiation and educates people about those effects.

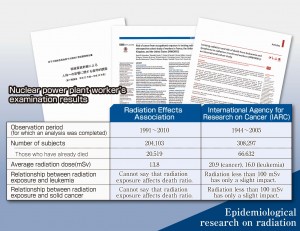

Unlike RERF’s epidemiological study, which only monitors the health conditions of the emergency workers at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, REA carries out follow-up research on the cancer deaths of 200,000 workers who were registered between 1990 and 1998. REA was commissioned to conduct this research by the Nuclear Regulation Authority.

The radiation doses of all nuclear power plant workers, including research subjects, are recorded at REA’s radiation workers’ registration center under a registration management system. Based on this data, REA performs a statistical analysis of the effects of radiation exposure while taking into account the additional dose of radiation received by workers who continued working at nuclear power plants after 1998.

REA compiles a report every five years and, in spring 2015, it released the results of its analysis made prior to 2010. According to the report, “Although, apparently, there seems to be a relationship between the radiation dose and various cancers, including liver cancer, smoking may also be a factor in causing cancer, and therefore it cannot be concluded that low-level radiation has an effect on mortality.”

Fumiyoshi Kasagi, the director of the Institute of Radiation Epidemiology at the Radiation Effects Association and once a former vice chief of RERF’s Epidemiology Department, stated, “Although epidemiology studies for nuclear power plant workers are carried out abroad, our research also carefully considers such factors as smoking and lifestyle that can have a significant impact on the development of cancer.

The results of a survey of 75,000 workers among a total of 200,000 subjects found that many of the workers with high radiation doses are smokers. For a more accurate analysis, REA has been holding explanatory meetings at electric power companies and nuclear power plants since the 2015 fiscal year to expand the number of subjects of its investigation into the lifestyle of all those still living among the 200,000 registered workers. It is not known, however, how many people will cooperate with this investigation.

The research results released overseas are different from RERF’s results. Last year, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), based in Lyon, France, publicized the results of its follow-up investigations which have been carried out since 1944 for 300,000 nuclear power plant workers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. These results indicate that a radiation dose which does not exceed 100 millisieverts nevertheless creates a slight increase in the risk of developing leukemia. IARC concluded that this finding also applies to deaths caused by solid cancers.

In epidemiological studies, the observation of a broad population of subjects leads to findings of minor changes in incidence rates and death rates. Even when considerable time and money is invested in such research, there are still cases where clear results cannot be obtained. Which institute’s research results correctly demonstrate the reality of radiation exposure? This has become a question of global proportions.

Epidemiological research on A-bomb survivors has been pursued since the 1950s

When clear-cut causes, the conditions of incidence, and the incidence rates of illness and communicable diseases cannot be identified, patients are divided into groups according to location, occupation, and lifestyle, and efforts to clarify these factors are made using statistical methods and by making comparisons of data between these groups. This process is known as epidemiological research.

The most well-known research concerning radiation-related diseases is the epidemiological research that the Radiation Effects Research Foundation has been pursuing since the 1950s. This research has involved a total of 120,000 people, both A-bomb survivors and those who were not directly exposed to the atomic bombing (including those who entered the city center within two kilometers of the hypocenter by August 20). In a survey of life expectancy, mortality rates were compared based on the cause of death. RERF also conducts an adult health study in which A-bomb survivors are given medical interviews and checkups every two years.

Through these efforts, it has been determined that the higher the dose of radiation exposure and the lower the survivor’s age at the time of the atomic bombing, the higher the risk is for developing leukemia and cancers affecting the lungs, stomach, and bowel.

Still, without long-term research, the whole picture of the relationship between radiation exposure and disease cannot be clarified. It was just a few years ago that those who were exposed to the atomic bomb within 1.5 kilometers of the hypocenter were found to have a high rate of incidence of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), which is known to be a precursor of leukemia.

The results of the research carried out on A-bomb survivors are made use of globally and serve as a basis for setting radiation protection standards. Even with that data, however, it is impossible to clarify the effects from low-level radiation of 100 millisieverts or less. The effects of internal exposure, where radioactive materials are taken into the body through air, water, and food, require further study.

(Originally published on April 15, 2016)

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Since the 2011 nuclear accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), many workers have been involved in the work to decommission the reactors and conclude these troubled conditions. Among them, 20,000 workers who entered the site prior to December 16, 2011, and have since been engaged in emergency tasks, are part of the government’s long-term measures to monitor the health of nuclear power plant workers as well as subjects in epidemiological studies on the health effects of radiation exposure. The organization responsible for these epidemiological studies is the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (RERF), located in Minami Ward, Hiroshima, which has amassed experience from the health examinations undertaken with A-bomb survivors. The question is: To what extent can the health effects from exposure to low-level radiation, the so-called “gray area,” be clarified scientifically? Hopes and challenges lie ahead for this effort, which will take decades to complete.

RERF to make use of knowledge and findings obtained in A-bombed cities

One after another, male workers arrived at the Iwaki Yoshima community medical checkup facility in Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture. This facility is one of 70 health institutions in Japan that are taking part in the “Epidemiological Studies Targeting Emergency Workers” at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant.

The medical checkups include a blood pressure check, blood sampling, and hearing and electrocardiograph tests. Yasunori Onishi, 44, a resident of Iwaki, said after his checkup that he agreed to undergo the tests because he would be able to receive an echocardiography (ultrasonic) examination of his thyroid gland, an organ that is vulnerable to radiation. Approximately three weeks after the nuclear accident, he was working as closely as 30 meters to Units 3 and 4. His role was to temporarily restore the power supply that had been lost as a consequence of the disaster. His work involved laying out electrical cables while keeping his distance from the wreckage. During this time, he was exposed to radiation of around 50 millisieverts. “It was turmoil,” he recalled, “and because my dosimeter wasn’t working properly, I may have actually been exposed to levels of radiation that were a little higher than the dosimeter readings.”

For nine months, between the time of the nuclear accident and December 16, 2011, the government raised the allowable exposure limit from 100 millisieverts to 250 millisieverts as part of its emergency measures. About 20,000 workers were assigned to dangerous work sites. Consequently, the radiation dose of 174 workers, including TEPCO employees, exceeded 100 millisieverts. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare designated all 20,000 personnel as “emergency workers,” and decided to make a database of their addresses and radiation doses to monitor their health and to use this data for an epidemiological study on the health effects from radiation. The Radiation Effects Research Foundation, which was commissioned to oversee the epidemiological study, moved forward in fiscal 2015 to fully implement the project.

As a result of its research involving A-bomb survivors, RERF has stated clearly that a relationship exists between radiation exposure and the incidence of cancer. However, can this conclusion be applied to gradual radiation exposure, as in the case of nuclear accidents, in the same way as instantaneous exposure, like in the atomic bombings? “It is our duty to make use of the knowledge that has accumulated in Hiroshima and Nagasaki and contribute to the research being undertaken for the nuclear power plant workers in Fukushima,” said Toshiteru Okubo, the former chairman of RERF, which is spearheading this research. On one wall of a room at RERF is a map of Japan that bears red dots indicating the addresses of all the emergency workers now scattered around the country. The data from the medical checkups for these people is being sent to RERF by the nation’s participating facilities.

For A-bomb survivors, RERF has been pursuing medical checkups as part of an “adult health study” and analyzes biological specimens from the subjects, including the blood samples that its collects. RERF’s know-how now serves as the basis for the epidemiological study of emergency workers in Fukushima. Compared to 70 years ago, when neither dosimeters nor correct name lists for the A-bomb survivors were available, the accuracy of the data compiled these days is quite high. Mr. Okubo believes that the health effects from exposure to low-level radiation of less than 100 millisieverts will eventually become clear.

Nevertheless, there are some challenges that have not been seen in research focused on A-bomb survivors, and both RERF and the medical examination facilities across Japan are struggling to address these issues.

Many nuclear power plant workers move from one plant to another around the country every few months, making it difficult to get information on their whereabouts or to arrange medical checkups a few months in advance. While travel expenses to the nearest medical examination facility are provided, emergency workers are concerned about compensation for lost wages if they take off a day to undergo this checkup. In addition, RERF has sent documents to the subjects of this research, asking them to cooperate with these examinations, but 8,000 workers, or 40% of the total, have not replied. As a result, RERF must remain tenacious in its efforts.

Haruhiko Tsukamoto, 55, an employee of one of TEPCO’s subcontractors, showed his understanding of the situation by saying that, because the Fukushima nuclear accident was an unprecedented disaster, he should cooperate by taking part in the health effects study. But he also pointed out that the company provides other regular checkups and many workers are reluctant to undergo multiple examinations.

In the past, RERF was criticized for its stance of not offering treatment for A-bomb survivors despite studying and examining them. It has taken a long time to obtain approval from the survivors so that the results of this research can be used to help prevent further victims of radiation. RERF’s efforts to gain the consent and confidence of the nuclear power plant workers have just begun.

Differing views expressed by Radiation Effects Association and International Agency for Research on Cancer

Epidemiological studies for nuclear power plant workers are also being conducted by the Radiation Effects Association (REA) in Chiyoda Ward, Tokyo. As part of a project to promote the peaceful use of nuclear energy, REA pursues research on the health effects of radiation and educates people about those effects.

Unlike RERF’s epidemiological study, which only monitors the health conditions of the emergency workers at the Fukushima No. 1 nuclear power plant, REA carries out follow-up research on the cancer deaths of 200,000 workers who were registered between 1990 and 1998. REA was commissioned to conduct this research by the Nuclear Regulation Authority.

The radiation doses of all nuclear power plant workers, including research subjects, are recorded at REA’s radiation workers’ registration center under a registration management system. Based on this data, REA performs a statistical analysis of the effects of radiation exposure while taking into account the additional dose of radiation received by workers who continued working at nuclear power plants after 1998.

REA compiles a report every five years and, in spring 2015, it released the results of its analysis made prior to 2010. According to the report, “Although, apparently, there seems to be a relationship between the radiation dose and various cancers, including liver cancer, smoking may also be a factor in causing cancer, and therefore it cannot be concluded that low-level radiation has an effect on mortality.”

Fumiyoshi Kasagi, the director of the Institute of Radiation Epidemiology at the Radiation Effects Association and once a former vice chief of RERF’s Epidemiology Department, stated, “Although epidemiology studies for nuclear power plant workers are carried out abroad, our research also carefully considers such factors as smoking and lifestyle that can have a significant impact on the development of cancer.

The results of a survey of 75,000 workers among a total of 200,000 subjects found that many of the workers with high radiation doses are smokers. For a more accurate analysis, REA has been holding explanatory meetings at electric power companies and nuclear power plants since the 2015 fiscal year to expand the number of subjects of its investigation into the lifestyle of all those still living among the 200,000 registered workers. It is not known, however, how many people will cooperate with this investigation.

The research results released overseas are different from RERF’s results. Last year, the International Agency for Research on Cancer (IARC), based in Lyon, France, publicized the results of its follow-up investigations which have been carried out since 1944 for 300,000 nuclear power plant workers in the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. These results indicate that a radiation dose which does not exceed 100 millisieverts nevertheless creates a slight increase in the risk of developing leukemia. IARC concluded that this finding also applies to deaths caused by solid cancers.

In epidemiological studies, the observation of a broad population of subjects leads to findings of minor changes in incidence rates and death rates. Even when considerable time and money is invested in such research, there are still cases where clear results cannot be obtained. Which institute’s research results correctly demonstrate the reality of radiation exposure? This has become a question of global proportions.

Epidemiological research on A-bomb survivors has been pursued since the 1950s

When clear-cut causes, the conditions of incidence, and the incidence rates of illness and communicable diseases cannot be identified, patients are divided into groups according to location, occupation, and lifestyle, and efforts to clarify these factors are made using statistical methods and by making comparisons of data between these groups. This process is known as epidemiological research.

The most well-known research concerning radiation-related diseases is the epidemiological research that the Radiation Effects Research Foundation has been pursuing since the 1950s. This research has involved a total of 120,000 people, both A-bomb survivors and those who were not directly exposed to the atomic bombing (including those who entered the city center within two kilometers of the hypocenter by August 20). In a survey of life expectancy, mortality rates were compared based on the cause of death. RERF also conducts an adult health study in which A-bomb survivors are given medical interviews and checkups every two years.

Through these efforts, it has been determined that the higher the dose of radiation exposure and the lower the survivor’s age at the time of the atomic bombing, the higher the risk is for developing leukemia and cancers affecting the lungs, stomach, and bowel.

Still, without long-term research, the whole picture of the relationship between radiation exposure and disease cannot be clarified. It was just a few years ago that those who were exposed to the atomic bomb within 1.5 kilometers of the hypocenter were found to have a high rate of incidence of myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS), which is known to be a precursor of leukemia.

The results of the research carried out on A-bomb survivors are made use of globally and serve as a basis for setting radiation protection standards. Even with that data, however, it is impossible to clarify the effects from low-level radiation of 100 millisieverts or less. The effects of internal exposure, where radioactive materials are taken into the body through air, water, and food, require further study.

(Originally published on April 15, 2016)