Summer of President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima: 52 significant minutes, Part 3

Jul. 22, 2016

Part 3: Frustration over nuclear disarmament felt by leader of A-bomb survivors

by Michiko Tanaka, Staff Writer

A 16-year-old boy’s house was flattened by the blast of the atomic bomb. Through a gap in the wreckage, only a meter away, he saw his mother trapped beneath debris but was unable to save her as fire closed in. “Mom, I’m sorry! I’ll die later, too!” he cried as he fled.

“I wonder what my mother was thinking in those raging flames. I still think about it,” said Mikiso Iwasa, 87, an A-bomb survivor from Funabashi, Chiba Prefecture and a chairperson of the Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), putting his hand to his chest. “I have carried this trauma here in my heart, and I went on with my life while haunted by the memory.”

Mother’s burnt body was unrecognizable

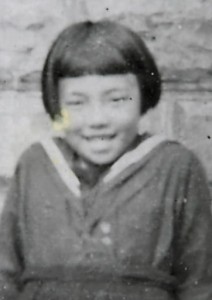

Mr. Iwasa’s father had already passed away from illness three months before the atomic bomb was dropped. At the time, Mr. Iwasa lived in Fujimi-cho (now part of Naka Ward) with his mother, Kiyoko, who was 45, and his sister, Yoshiko, then 12 and a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Girls’ High School (now Minami High School). He loved her, calling her “Yotchan.” He was a student in the advanced course at Shudo Junior High School and held no doubts about being mobilized to work at a munitions factory. “I was so shallow that I even dreamed of dying on the battlefield, and I believed, by doing so, I would be protecting my country and my family.”

On the morning of August 6, 1945, he had a day off from the factory and was at home, about 1.2 kilometers from the hypocenter. After bidding goodbye to his sister, who was mobilized to help tear down houses to create a fire lane, he was out in the yard when the bomb’s massive blast knocked him to the ground.

Miraculously, Mr. Iwasa suffered only minor injuries, but he was unable to reach his mother, who was pinned under the wreckage of their home. “Run away quickly!” his mother told him, then began to chant the Heart Sutra. Several days after the bombing, her body was recovered from the rubble. “Her body looked like a burnt mannequin coated with coal tar,” he recalled. He was unable to find his sister, who would have been near Dobashi-cho (now part of Naka Ward), and he hated the atomic bombing and the cruel way it forced human beings to die with no dignity.

After the war, he was supported by his aunt, who lost her husband in the atomic bombing. He then went on to college and because a scholar of the history of political thought of the United Kingdom. In 1954, when he was teaching at Kanazawa University, the crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat, were exposed to the radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll. At that point, as criticism rose against nuclear testing, he began to get involved in antinuclear activities. “The driving force was my hatred toward the war,” Mr. Iwasa said. In 1960, he formed a group of A-bomb survivors in Ishikawa Prefecture. In 1994, after his retirement, he moved to the city of Funabashi, near where his daughter lived, and joined the efforts of Nihon Hidankyo. Since 2011, he has been a chairperson of the group, helping to spearhead their work.

“Peace” inscribed on family gravestone

Mr. Iwasa was invited to attend the ceremony when U.S. President Barack Obama gave a speech in Hiroshima during his visit to the A-bombed city on May 27. However, a few days before the event, he was brought to the hospital by ambulance and was in poor condition. Still, he traveled to Hiroshima by bullet train, telling himself, “I’m acting on behalf of the A-bomb survivors.” Though he was unable to speak with Mr. Obama in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park, he said that he agreed with the message of the president’s speech in asking us to look directly into the eye of the A-bombed city and learn the lesson of Hiroshima. He felt that Mr. Obama’s speech shared common ground with his faith.

Mr. Iwasa added, though: “His visit won’t accomplish anything if it was only talk.” Little progress is being made in nuclear disarmament, and nations are facing off as they strengthen their military might. “Unless clear progress is made toward a world without nuclear weapons and war, I can’t tell my mother and sister that they didn’t die in vain.”

Ten years ago, Mr. Iwasa moved his family’s plot from Hiroshima to a site near his home. The gravestone is inscribed “With eternal prayers for peace,” reflecting his fervent hope that, as long as he lives, he can continue making every effort to promote peace. This year, again, the anniversary of the deaths of his family members are approaching. He plans to go to Hiroshima and attend various gatherings, where he will urge people to work together.

(Originally published on July 22, 2016)