Survivors’ Stories: Shinobu Sunakawa, 83, Minami Ward, Hiroshima

Jun. 6, 2016

Reunited with his mother after the atomic bombing

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

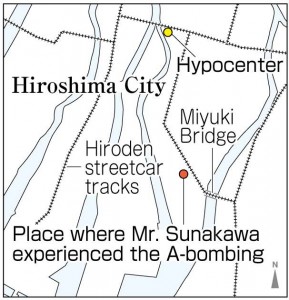

The day after the atomic bombing, Shinobu Sunakawa, 83, was at the east end of Miyuki Bridge (now part of Minmai Ward), on the southern bank of the river. He was alone, and at a loss, when his mother, Kome, found him. The two had given each other up for dead but were finally reunited. Mr. Sunakawa choked on the words as he described that moment, when we wept tears of joy. Standing on this spot, he becomes swept up in the memories of that day.

Back then, Mr. Sunakawa was 12 years old and a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School. To help on the family farm, he had returned to his home on Kurahashi Island (now part of Kure), but on August 5, 1945, he came to Hiroshima with his mother to support the war effort by tearing down homes to create a firebreak in the event of air raids. Mr. Sunakawa had a stomachache so they visited the home of his mother’s friend, Takeo Saeki, in Sendamachi (now part of Naka Ward) so he could rest. After seeing off his mother, who headed to Kumano-cho to buy rice that evening, he remained at Mr. Saeki’s home rather than going to the school dormitory in Yoshijima-honmachi (now part of Naka Ward).

On the morning of the following day, August 6, he went to the kitchen to get some medicine and heard the drone of an American B-29 bomber. He wondered why an air raid warning had not sounded. He posed this question to a group of adults who were working on a firebreak in the neighborhood and they told him to turn on the radio. As he reentered the house, there was a bright flash of many colors, red and blue among them, and a massive blast.

He was about 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. Before his eyes, the leaves of a fig tree in front of the house shriveled up. With a cry he ducked down and covered his eyes and ears with his hands, but he became trapped under the falling building and could not budge his arms or legs. About seven hours later, when he was rescued by adults from the neighborhood, the city center was veiled in thick smoke. Mr. Sunakawa then fled to Miyuki Bridge with members of Mr. Saeki’s family.

When they arrived at the bridge, they were unable to locate Mr. Saeki’s eldest son, a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School), who should have made his way back home and joined them there. Mr. Sunakawa accompanied some adults to look for him at a first-aid station established at a warehouse of the army corps of engineers (now part of Minami Ward). Checking each boy there, he put wet cotton in their mouths when they begged for water. In the end, they were unable to find Mr. Saeki’s son, whose remains were never recovered. They spent a sleepless night by Miyuki Bridge as they watched the Monopoly Bureau building, to the north, in flames.

All around Miyuki Bridge were scores of dead and wounded. Mr. Sunakawa recalled the horrifying sight of bodies piled up onto trucks like baggage. As he thought helplessly of his mother, wanting to return to their island to see her, she abruptly appeared. She had returned to Hiroshima Station from Kumano-cho on August 7, then searched for her son’s face in the bodies that covered the streets, even rolling over the dead that lay face down. The next day, August 8, mother and son headed back to Kurahashi Island.

Many of Mr. Sunakawa’s schoolmates perished in the bombing while helping to tear down homes to create a firebreak in Nakajima-shinmachi (now part of Naka Ward). After the war, he studied architecture and, starting in 1953, worked for the Hiroshima municipal government. He sought to create buildings that everyone would find easy to use, including the Asakita and Asaminami ward buildings. He hoped that these areas would prosper through the construction of good public facilities.

When U.S. President Barack Obama visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park on May 27, Mr. Sunakawa’s eyes were fixed on the live TV images. “I don’t hate the United States, but I’m absolutely against nuclear weapons,” he said. “Everyone has different ideas, though. I’d like young people today to think about what they can do for peace, not simply have other people tell them what to do.” He hopes that younger generations won’t experience the kind of grief and hardship that he had to endure.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Bitterness disappears with compassion

After the atomic bombing, Mr. Sunakawa felt bitter toward the United States. But when he shared his A-bomb account at the Peace Memorial Park and an American couple told him they were sorry for the hardships he experienced, he was happy. War makes people bitter. But if we try to understand one another, with compassion, that bitterness will disappear. I think compassion is important for building peace. (Yukiho Saito, 14)

Thinking about what I can do for peace

What can we do for peace? When I asked Mr. Sunakawa this question, he said I should think it over myself. Right now I’m a junior writer and I gather information and write articles. But I didn’t consider what I will do after I’m no longer in this role. He told me to think for myself, and I realized I have to find my own answers, even though I feel unsure. (Miki Meguro, 13)

Understanding the horror of the A-bombing

I was glad I had the chance to hear Mr. Sunakawa’s story of being rescued from the wrecked house and getting reunited with his mother afterward. Because Mr. Sunakawa was able to overcome hardships that we can hardly imagine and share his story with us, I could understand the horror of the atomic bombing and war. I want to help create a future where everyone can be happy and not have to face the kind of experience Mr. Sunakawa had. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi, 14)

(Originally published on June 6, 2016)

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

The day after the atomic bombing, Shinobu Sunakawa, 83, was at the east end of Miyuki Bridge (now part of Minmai Ward), on the southern bank of the river. He was alone, and at a loss, when his mother, Kome, found him. The two had given each other up for dead but were finally reunited. Mr. Sunakawa choked on the words as he described that moment, when we wept tears of joy. Standing on this spot, he becomes swept up in the memories of that day.

Back then, Mr. Sunakawa was 12 years old and a first-year student at Hiroshima Prefectural Hiroshima Technical High School. To help on the family farm, he had returned to his home on Kurahashi Island (now part of Kure), but on August 5, 1945, he came to Hiroshima with his mother to support the war effort by tearing down homes to create a firebreak in the event of air raids. Mr. Sunakawa had a stomachache so they visited the home of his mother’s friend, Takeo Saeki, in Sendamachi (now part of Naka Ward) so he could rest. After seeing off his mother, who headed to Kumano-cho to buy rice that evening, he remained at Mr. Saeki’s home rather than going to the school dormitory in Yoshijima-honmachi (now part of Naka Ward).

On the morning of the following day, August 6, he went to the kitchen to get some medicine and heard the drone of an American B-29 bomber. He wondered why an air raid warning had not sounded. He posed this question to a group of adults who were working on a firebreak in the neighborhood and they told him to turn on the radio. As he reentered the house, there was a bright flash of many colors, red and blue among them, and a massive blast.

He was about 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. Before his eyes, the leaves of a fig tree in front of the house shriveled up. With a cry he ducked down and covered his eyes and ears with his hands, but he became trapped under the falling building and could not budge his arms or legs. About seven hours later, when he was rescued by adults from the neighborhood, the city center was veiled in thick smoke. Mr. Sunakawa then fled to Miyuki Bridge with members of Mr. Saeki’s family.

When they arrived at the bridge, they were unable to locate Mr. Saeki’s eldest son, a first-year student at First Hiroshima Prefectural Junior High School (now Kokutaiji High School), who should have made his way back home and joined them there. Mr. Sunakawa accompanied some adults to look for him at a first-aid station established at a warehouse of the army corps of engineers (now part of Minami Ward). Checking each boy there, he put wet cotton in their mouths when they begged for water. In the end, they were unable to find Mr. Saeki’s son, whose remains were never recovered. They spent a sleepless night by Miyuki Bridge as they watched the Monopoly Bureau building, to the north, in flames.

All around Miyuki Bridge were scores of dead and wounded. Mr. Sunakawa recalled the horrifying sight of bodies piled up onto trucks like baggage. As he thought helplessly of his mother, wanting to return to their island to see her, she abruptly appeared. She had returned to Hiroshima Station from Kumano-cho on August 7, then searched for her son’s face in the bodies that covered the streets, even rolling over the dead that lay face down. The next day, August 8, mother and son headed back to Kurahashi Island.

Many of Mr. Sunakawa’s schoolmates perished in the bombing while helping to tear down homes to create a firebreak in Nakajima-shinmachi (now part of Naka Ward). After the war, he studied architecture and, starting in 1953, worked for the Hiroshima municipal government. He sought to create buildings that everyone would find easy to use, including the Asakita and Asaminami ward buildings. He hoped that these areas would prosper through the construction of good public facilities.

When U.S. President Barack Obama visited the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park on May 27, Mr. Sunakawa’s eyes were fixed on the live TV images. “I don’t hate the United States, but I’m absolutely against nuclear weapons,” he said. “Everyone has different ideas, though. I’d like young people today to think about what they can do for peace, not simply have other people tell them what to do.” He hopes that younger generations won’t experience the kind of grief and hardship that he had to endure.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Bitterness disappears with compassion

After the atomic bombing, Mr. Sunakawa felt bitter toward the United States. But when he shared his A-bomb account at the Peace Memorial Park and an American couple told him they were sorry for the hardships he experienced, he was happy. War makes people bitter. But if we try to understand one another, with compassion, that bitterness will disappear. I think compassion is important for building peace. (Yukiho Saito, 14)

Thinking about what I can do for peace

What can we do for peace? When I asked Mr. Sunakawa this question, he said I should think it over myself. Right now I’m a junior writer and I gather information and write articles. But I didn’t consider what I will do after I’m no longer in this role. He told me to think for myself, and I realized I have to find my own answers, even though I feel unsure. (Miki Meguro, 13)

Understanding the horror of the A-bombing

I was glad I had the chance to hear Mr. Sunakawa’s story of being rescued from the wrecked house and getting reunited with his mother afterward. Because Mr. Sunakawa was able to overcome hardships that we can hardly imagine and share his story with us, I could understand the horror of the atomic bombing and war. I want to help create a future where everyone can be happy and not have to face the kind of experience Mr. Sunakawa had. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi, 14)

(Originally published on June 6, 2016)