Summer of President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima: 52 significant minutes, Part 8

Jul. 29, 2016

Part 8: Preserving A-bomb artifacts and A-bomb memories, advancing nuclear abolition

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

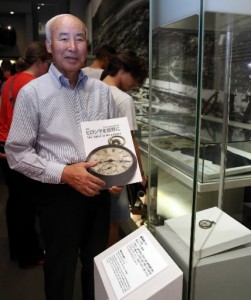

When visitors to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum see a pocket watch with its hands frozen at 8:15 a.m., they are reminded of the moment Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb. Part of the museum’s collection, a photo of this watch is featured on the cover of the museum’s 127-page book entitledThe Spirit of Hiroshima, which includes photos of more personal effects of the A-bomb victims. When U.S. President Barack Obama came to the museum on May 27, museum staff gifted a copy of this book to him to commemorate his visit.

Grandfather’s pocket watch appears on the cover

Kiyoshi Nikawa, 73, an A-bomb survivor and resident of Saka in Hiroshima Prefecture, said, “I hope President Obama keeps the book close by and looks at it again and again to better understand the devastating reality of the atomic bombing and the pain of family members of the A-bomb victims. I think my father would have felt the same way if he were still alive.”

Kazuo Nikawa was Mr. Nikawa’s father and he died in 2001 at the age of 89. He bought the pocket watch in China around 1940 when he traveled there as a crew member of a military ship. Kengo Nikawa, Mr. Nikawa’s grandfather, then kept the watch after receiving it from his son as a gift.

When the atomic bomb exploded on August 6, 1945, Kengo was at the Kannon Bridge, located about 1.6 kilometers southeast of the hypocenter. He suffered severe burns and fled to a relative’s house on the outskirts of town, but died on August 22 at the age of 59. Though Kazuo made it to Hiroshima that day, coming from his military post, he was unable to reach his father before he died.

In 1975, the year that marked the 30th anniversary of the atomic bombing, Kazuo donated his father’s watch to the museum. Until then, he had treasured it at home, at the family’s Buddhist altar. Mr. Nikawa said, “I think my father felt remorse over the fact that he was unable to be with his father, who had loved and cared for his children so much, when he was dying.”

The personal effects of the A-bomb victims continue to convey memories of the atomic bombing. With the average age of the survivors now nearly 81, which makes it increasingly difficult for them to personally share their accounts of the bombing with others, such artifacts, more than ever before, play an important role in handing down the experience of the atomic bombing to younger generations.

At this point, though, the museum faces the urgent task of assessing the deterioration of the items in its collection and taking suitable steps to preserve them. The small hand on Mr. Nikawa’s pocket watch, which had been on display in the museum, was found rusted and broken last summer. This symbolizes the passage of time, the more than 70 years that have gone by, since the atomic bombing.

Granddaughter shows more interest in the A-bombing

The city of Hiroshima is charged with the mission of communicating the horror of nuclear weapons to the world, resisting the passage of time that makes the memory of the atomic bombing fade. President Obama’s historic visit in May has offered the opportunity for the city to return to this basic principle.

Masaru Murata, 72, a resident of Naka Ward, said, “Thanks to President Obama’s visit, my granddaughter is now apparently more interested in the atomic bombing. And for me, personally, I was able to listen to a family member’s experience of the bombing and talk about it with my daughter and granddaughter.”

The chance to trace the A-bomb experience in his family arose because Waka Takemoto, 12, Mr. Murata’s granddaughter and a sixth grader at Nakajima Elementary School, was invited to take part in the ceremony held in connection with President Obama’s visit to the Peace Memorial Park.

During the war, Mr. Murata’s parents ran a variety store that sat south of the Rest House in the park. Before the bombing, his family had evacuated the area.

This summer Mr. Murata’s elder sister described in detail what she experienced in the aftermath of the A-bomb attack. Referring to the place where their home had once stood, she said, “By the pond on the grounds of the temple, where I used to play, I found a turtle that looked like it was crawling as usual, but it was charred and dead.” She had gone there to search for her father, who was mobilized to help with the war effort. Mr. Murata then shared his sister’s story with his eldest daughter, Chieko Takemoto, 43, and Chieko’s daughter, Waka. As his daughter and granddaughter listened intently, Mr. Murata was struck by the fact that there were still things he didn’t know about the atomic bombing, things he was unable to share.

The president of the United States, the nation that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, tread the ground of the Peace Memorial Park for 52 minutes. Consequently, the people of Hiroshima are urging the leader of the nuclear superpower to take action to advance a world without nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, his visit has brought Hiroshima citizens back to the basic principle of conveying the A-bomb memories, which must be handed down to the generations that follow.

(Originally published on July 29, 2016)

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

When visitors to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum see a pocket watch with its hands frozen at 8:15 a.m., they are reminded of the moment Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb. Part of the museum’s collection, a photo of this watch is featured on the cover of the museum’s 127-page book entitledThe Spirit of Hiroshima, which includes photos of more personal effects of the A-bomb victims. When U.S. President Barack Obama came to the museum on May 27, museum staff gifted a copy of this book to him to commemorate his visit.

Grandfather’s pocket watch appears on the cover

Kiyoshi Nikawa, 73, an A-bomb survivor and resident of Saka in Hiroshima Prefecture, said, “I hope President Obama keeps the book close by and looks at it again and again to better understand the devastating reality of the atomic bombing and the pain of family members of the A-bomb victims. I think my father would have felt the same way if he were still alive.”

Kazuo Nikawa was Mr. Nikawa’s father and he died in 2001 at the age of 89. He bought the pocket watch in China around 1940 when he traveled there as a crew member of a military ship. Kengo Nikawa, Mr. Nikawa’s grandfather, then kept the watch after receiving it from his son as a gift.

When the atomic bomb exploded on August 6, 1945, Kengo was at the Kannon Bridge, located about 1.6 kilometers southeast of the hypocenter. He suffered severe burns and fled to a relative’s house on the outskirts of town, but died on August 22 at the age of 59. Though Kazuo made it to Hiroshima that day, coming from his military post, he was unable to reach his father before he died.

In 1975, the year that marked the 30th anniversary of the atomic bombing, Kazuo donated his father’s watch to the museum. Until then, he had treasured it at home, at the family’s Buddhist altar. Mr. Nikawa said, “I think my father felt remorse over the fact that he was unable to be with his father, who had loved and cared for his children so much, when he was dying.”

The personal effects of the A-bomb victims continue to convey memories of the atomic bombing. With the average age of the survivors now nearly 81, which makes it increasingly difficult for them to personally share their accounts of the bombing with others, such artifacts, more than ever before, play an important role in handing down the experience of the atomic bombing to younger generations.

At this point, though, the museum faces the urgent task of assessing the deterioration of the items in its collection and taking suitable steps to preserve them. The small hand on Mr. Nikawa’s pocket watch, which had been on display in the museum, was found rusted and broken last summer. This symbolizes the passage of time, the more than 70 years that have gone by, since the atomic bombing.

Granddaughter shows more interest in the A-bombing

The city of Hiroshima is charged with the mission of communicating the horror of nuclear weapons to the world, resisting the passage of time that makes the memory of the atomic bombing fade. President Obama’s historic visit in May has offered the opportunity for the city to return to this basic principle.

Masaru Murata, 72, a resident of Naka Ward, said, “Thanks to President Obama’s visit, my granddaughter is now apparently more interested in the atomic bombing. And for me, personally, I was able to listen to a family member’s experience of the bombing and talk about it with my daughter and granddaughter.”

The chance to trace the A-bomb experience in his family arose because Waka Takemoto, 12, Mr. Murata’s granddaughter and a sixth grader at Nakajima Elementary School, was invited to take part in the ceremony held in connection with President Obama’s visit to the Peace Memorial Park.

During the war, Mr. Murata’s parents ran a variety store that sat south of the Rest House in the park. Before the bombing, his family had evacuated the area.

This summer Mr. Murata’s elder sister described in detail what she experienced in the aftermath of the A-bomb attack. Referring to the place where their home had once stood, she said, “By the pond on the grounds of the temple, where I used to play, I found a turtle that looked like it was crawling as usual, but it was charred and dead.” She had gone there to search for her father, who was mobilized to help with the war effort. Mr. Murata then shared his sister’s story with his eldest daughter, Chieko Takemoto, 43, and Chieko’s daughter, Waka. As his daughter and granddaughter listened intently, Mr. Murata was struck by the fact that there were still things he didn’t know about the atomic bombing, things he was unable to share.

The president of the United States, the nation that dropped the atomic bomb on Hiroshima, tread the ground of the Peace Memorial Park for 52 minutes. Consequently, the people of Hiroshima are urging the leader of the nuclear superpower to take action to advance a world without nuclear weapons. Meanwhile, his visit has brought Hiroshima citizens back to the basic principle of conveying the A-bomb memories, which must be handed down to the generations that follow.

(Originally published on July 29, 2016)