Summer of President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima: Survey of A-bomb survivors’ groups across Japan

Jul. 31, 2016

Survey shows urgent desire for concrete measures to advance nuclear abolition

by Michiko Tanaka and Hidetoshi Arioka, Staff Writers

According to a survey conducted by the Chugoku Shimbun, nearly 90% of the groups of A-bomb survivors in five prefectures in the Chugoku region and the prefectural A-bomb survivors’ groups in other parts of Japan view U.S. President Barack Obama’s visit to Hiroshima in May positively. At the same time, the respondents of the groups expressed some dissatisfaction because Mr. Obama failed to make any concrete proposals for advancing nuclear disarmament in his “Hiroshima Speech,” and he avoided apologizing for the atomic bombings carried out by the United States. The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), the only national group of A-bomb survivors, marks its 60th anniversary on August 10. Now, with key figures in the survivors’ movement, which seeks to prevent more sufferers of nuclear weapons, advancing in age, their urgent hope is that a world without nuclear arms can be realized as soon as possible.

Impressions of President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima

How do A-bomb survivors feel about President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima on May 27? In all, 105 out of 115 groups responded to this question in the survey. The respondents of 94 groups (89.5%) said that “it was very meaningful” or “it was reasonably meaningful,” indicating broad support for the first-ever visit to the A-bombed city by a sitting American president.

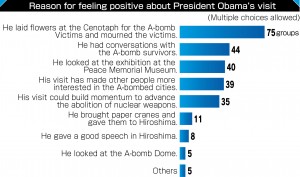

President Obama was present in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park for 52 minutes. When asked for reasons to account for their evaluation of his visit (multiple choices were allowed), the respondents of 75 groups, or 70% of the groups expressing a favorable assessment of the visit, chose the option “He offered flowers at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and mourned the victims.” It seems the president’s act of laying a wreath of white flowers and pausing for five seconds, eyes closed, in front of the cenotaph, was a potent appeal to the survivors’ emotions.

In the comments section of the survey, the respondents also pointed to the significance of Mr. Obama’s visit. For example, the comment from a group of A-bomb survivors in Miyagi Prefecture said, “It was meaningful that he delivered a message from the A-bombed city to the world,” and a survivors’ group in Tottori Prefecture commented, “His visit has made it easier for leaders of other nations to visit the A-bombed cities.”

The respondents of more than 40 groups also looked favorably on President Obama’s interactions with two A-bomb survivors who were invited to attend the event, Sunao Tsuboi, 91, the co-chair of Nihon Hidankyo, and Shigeaki Mori, 79, a local historian, as well as the president’s visit to the Peace Memorial Museum to see a special exhibition featuring personal effects of the victims and photos showing the devastated city in the aftermath of the atomic bombing.

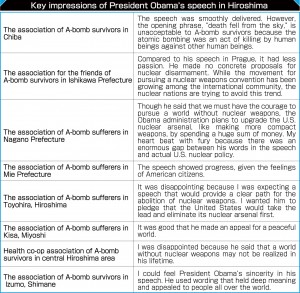

Meanwhile, only eight groups were pleased with President Obama’s 17-minute speech. There were a few favorable comments about the address, like this comment from a group in Yamanashi Prefecture: “He was in a difficult position, considering U.S. public opinion justifies the atomic bombings, and he worded the speech as best he could.” However, the respondents of 10 groups were disturbed by the opening sentence in the president’s speech--“Seventy-one years ago, on a bright cloudless morning, death fell from the sky and the world was changed”--because they felt this showed no sense of responsibility, as the head of the nation which dropped the atomic bombs.

The respondents of some groups also faulted the speech for not including a concrete vision or measures to advance the aim of nuclear abolition. After the speech Mr. Obama made in Prague in April 2009, when he articulated comprehensive ideas for addressing nuclear issues and which had a large impact on A-bomb survivors, they seem to feel that his speech in Hiroshima fell short as a message made from the A-bombed city.

The respondents of several groups said, in the comments section, that they would redouble their efforts in reaction to the president’s visit. The group in Hiroshima indicated their resolve by including their next concrete steps. The respondent of the group said that they plan to take part in the global signature drive led by Nihon Hidankyo and send letters to the leaders of the nuclear weapon states with references to President Obama’s speech.

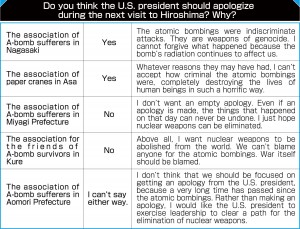

Survivors feel torn over question of apologizing for A-bombings

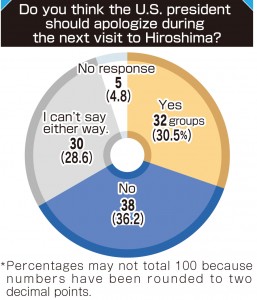

While in Hiroshima, Mr. Obama offered no words of apology to the A-bomb survivors. The Chugoku Shimbun survey asked whether or not an American president should apologize when visiting the A-bombed cities in the future. Of the 105 groups asked, 32 groups said “Yes” and 38 said “No,” with 30 groups responding “I can’t say either way.” These three answers, equally split, convey the complex emotions of the survivors. The remaining five groups made no selection.

The respondents of the groups seeking an apology from the president stress U.S. responsibility for the inhumane suffering wrought by the atomic bombing. A group in Fukushima Prefecture commented, “Many innocent people, including non-combatants, were killed or injured in the atomic bombings,” while a group in Ishikawa Prefecture said, “Poor health stemming from A-bomb radiation, or anxiety about their health, has been the inheritance of second- and third-generation A-bomb survivors.”

Meanwhile, groups in Akitakata and Mukaihara said, “Rather than receiving an apology about the past, if the president takes concrete action for the future, to advance nuclear abolition, that would be the most significant atonement for us.” As this comment indicates, the respondents of the group who said that no apology from the president was required nevertheless expressed their hopes that the president, as the head of the nuclear superpower, would exercise leadership to realize the abolition of nuclear arms, the deep desire of A-bomb survivors.

As for the groups who said “I can’t say either way,” they said that it was too late to receive an apology, 71 years after the atomic bombings, and that Japan holds its share of responsibility for having undertaken the attack on Pearl Harbor.

70% have felt anger toward the United States

When they were surveyed about their feelings toward the United States, the country that dropped the atomic bombs, 100 groups responded. Of this number, 36 groups said, “I still feel angry” while 34 groups answered, “I used to feel angry,” totaling 70%.

Notably, there were respondents who described their emotions as a result of losing family members or friends. The respondent of a group in Fukuoka Prefecture commented, “My elder sister died in the atomic bombing at the age of 14. It’s unforgivable that innocent people were killed,” and the respondent of a group in the towns of Sera and Seranishi said, “My three siblings were killed in the atomic bombing. I will never forget that horror.” Also, a respondent of a group in the area of Ube, Sanyo, and Ononda reflected on the past and wrote, “Because my health was poor for a while, I felt angry about the atomic bombing back then, wondering what the war was all about and why this had happened to me.”

Meanwhile, the respondents of 13 groups said that they did not feel anger toward the United States. The respondent of a group in Tochigi Prefecture commented, “It was a war so both nations are to blame. The origin of our movement is our wish that the generations which follow will never have to experience the same suffering.” For this survey question, the respondents of 17 groups chose to answer, “I can’t say either way.”

Strengthening their appeal for nuclear abolition, in and out of Japan

On April 27, one month prior to President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima, a member of Nihon Hidankyo appealed to the people streaming past in front of JR Shibuya Station in Shibuya Ward, Tokyo, calling, “I don’t want anyone else to suffer what I’ve experienced. Could you please help by signing our petition?”

In March, Nihon Hidankyo proposed a global signature drive that calls for a nuclear weapons convention to ban and eliminate the earth’s nuclear arms. In the international community, nations which don’t possess or rely on nuclear weapons have been strengthening their efforts to have them banned, based on their inhumane impact. In response to this movement, the aging A-bomb survivors have been making a stronger appeal to people in Japan and overseas.

Since it was established on August 10, 1956, Nihon Hidankyo has been resolved to reach out to the international community. In the declaration made at its founding, titled “Message to the World,” the group vowed to help save humanity from the perils of nuclear weapons through the lessons learned from the survivors’ experiences. Representatives of the group have been dispatched abroad on many occasions.

Unfortunately, during the Cold War era, a number of countries, particularly the United States and the Soviet Union, engaged in an escalating arms race. Today, there are still more than 15,000 nuclear weapons in the world. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which was enacted in 1970, permits the five main nuclear powers to possess nuclear arms yet obliges them to work toward nuclear disarmament. However, very little progress in this direction has been made to date. Nihon Hidankyo has been sending delegations to the NPT Review Conference, held every five years, where all the nations that have ratified the NPT gather to discuss actions for nuclear disarmament. But the collapse of the recent Review Conference, held in 2015, was deeply disappointing to them.

As of the end of this past March, the average age of the A-bomb survivors is 80.86. With an increasing number of people becoming aware of the inhumanity of nuclear weapons, the survivors are receiving more frequent requests to share their A-bomb accounts at international conferences. But because of their advancing age, the “younger” survivors, who actually have no memory of that time because they experienced it in early childhood, must often step in to fulfill these requests.

Toshiki Fujimori, 72, the assistant secretary general of Nihon Hidankyo, spoke about his A-bomb experience at a meeting of the U.N. working group on nuclear disarmament, which took place in Geneva, Switzerland in May. “My story may be less vivid than an account from an older survivor who has clear memories of the atomic bombing,” he said. “But I think I can share my experience and my feelings with listeners, since my mother and others told me all about what happened.”

Seeking to help sway the world toward nuclear abolition, the A-bomb survivors continue to exert themselves in Japan and out among the international community.

Groups seek to share A-bomb accounts more frequently

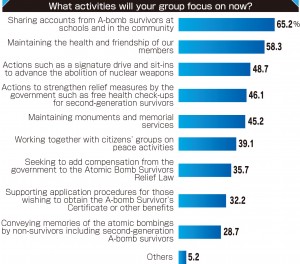

Surveyed about their activities for the future (multiple choices were allowed), 115 groups offered responses. The largest number of respondents, from 75 groups (65.2% of the total), chose “Sharing A-bomb survivors’ accounts of the atomic bombings at schools and in the community.” The percentage for this question rose by 5.7 points compared to the percentage for the same question asked by the Chugoku Shimbun in a survey last year to mark the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing. This indicates the desire of A-bomb survivors to hand down the reality of the bombings to the next generations by persevering in their efforts to share their experiences.

In addition, the respondents of 67 groups (58.3%) selected “Maintaining the health and friendship of our members,” while 56 groups (48.7%) said “Actions like a signature drive and sit-ins to advance the abolition of nuclear weapons.” These answers, too, earned slightly higher percentages than in last year’s survey. The survivors’ resolve to support one another and work for nuclear disarmament remains strong.

The respondents of 53 groups (46.1%) also chose “Actions to strengthen relief measures by the government, such as free health check-ups for second-generation survivors,” putting emphasis on providing support for second-generation survivors, who will assume greater responsibility for the groups’ activities in the future. Also selected, by 52 groups (45.2%), was “Maintaining monuments and memorial services,” which indicates that the survivors wish to continue mourning the victims even if their groups become inactive due to their advancing age.

Groups continue their efforts to expand relief measures

The A-bomb survivors endured “the lost decade” after the atomic bombings. During this time they were forced to face their hardships alone because there were virtually no avenues of public or private support. These conditions changed, though, in March 1954, when the crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat, were exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll. As the movement to ban A- and H-bombs started to spread, the A-bomb survivors began making their voices heard.

In 1957, the Japanese government started issuing the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and covering the costs of treatment for A-bomb-related diseases. These first relief measures have since been changed dozens of times over the years as Nihon Hidakyo pursued efforts that included sit-ins, marches, and petitions to the Japanese Diet. For instance, in 1968, the government began providing a number of new benefits to A-bomb survivors, including a health management allowance.

However, the group’s greatest desire, that the Japanese government compensate the sufferers for radiation damage caused by the atomic bombs, has not yet materialized. The group holds the basic conviction that forcing the government to compensate for the damages caused by the atomic bombings, which were brought on by the war Japan waged, will lead to the goal of no more nuclear sufferers. The government, though, has continued to rebuff the idea of providing compensation to the A-bomb survivors, contending that the population must endure the sacrifices of war equally.

Meanwhile, lawsuits over the government’s authorization of A-bomb diseases continue in Japanese courts. Nihon Hidankyo has demanded that the government establish a new allowance system, which could increase the amount of allowance in line with each survivor’s symptoms, thus abandoning the current certification system, which has enabled the government to make judgments based on a defined standard of diseases and conditions. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has not met this request, however, arguing that the current standard, created after a series of discussions, is valuable.

Secretary general of Nihon Hidankyo wants President Obama’s visit to inspire action

The Chugoku Shimbun spoke with Terumi Tanaka, 84, the secretary general of Nihon Hidankyo, about his thoughts on the survey results and the challenges that lie ahead. Below are his comments.

The A-bomb survivors have had high hopes for President Obama, who has advocated “a world without nuclear weapons.” Even if some survivors are not fully satisfied by his words and actions in Hiroshima, they may look favorably on his visit, considering that his actions in Hiroshima were likely restrained by the conditions in his own nation.

What really matters are concrete efforts to realize the abolition of nuclear arms. In his speech, President Obama didn’t offer any specific measures for advancing nuclear disarmament. Along with the fact that he avoided the question of U.S. responsibility for dropping the atomic bombs, we plan to make use of the issues raised by his visit to pursue further efforts in the future.

Because of the hard reality that younger people will need to take over our activities, we must familiarize them not only with the devastation caused by the bombings but also with the progress made by the survivors’ movement, including our thoughts and feelings, our aims and actions, and the goals that must still be fulfilled. We have been putting all this down in documents that can be used for reference. I hope the younger generations will understand the spirit of our movement and carry on with our initiatives in their own way.

Nuclear weapons have not yet been eliminated because this is a problem that concerns us all, not only the A-bomb survivors. We launched a global signature drive to lend support to the movement which seeks to create a legal ban on nuclear arms because we feel a sense of crisis that nothing will change if simply left up to the actions of politicians. Through our efforts, we want to provide the opportunity for citizens in the nuclear nations to consider this issue more carefully.

Highlights of the movement by A-bomb survivors and Nihon Hidankyo

August 6, 1945

The United States drops the the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. A second atomic bomb is dropped on Nagasaki on August 9.

August 27, 1951

Kiyoshi Kikkawa and about 20 A-bomb survivors form the Rehabilitation Group for A-bomb Survivors.

August 10, 1952

Mr. Kikkawa, poet Sankichi Toge, and about 50 A-bomb survivors establish the Atomic Bomb Survivors Association in Hiroshima.

March 1, 1954

The crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat, are exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll.

August 6, 1955

The first World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs is held in Hiroshima.

September 19, 1955

The Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Gensuikyo) is established.

May 27, 1956

The Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations is established.

August 10, 1956

The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) is established. The head office is placed in Hiroshima. Heiichi Fuji is elected secretary general.

March 25, 1957

A-bomb survivors stage a sit-in protest in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, calling for a halt to hydrogen bomb tests by the United Kingdom.

April 1, 1957

The Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law comes into effect. The Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate begins to be issued to A-bomb survivors.

February 17, 1961

Nihon Hidankyo holds a gathering to petition the Diet for the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law. The group makes its first march from Hibiya to Shinbashi.

August 5, 1963

The 9th World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs faces disarray among the participants.

February 1, 1965

13 groups including the General Council of Trade Unions establish the Japan Congress against A- and H- Bombs (Gensuikin).

November 1, 1965

The Ministry of Health and Welfare conducts the first nationwide fact-finding survey of A-bomb survivors.

October 15, 1966

Nihon Hidankyo releases “Characteristics of the A-bomb Damage and the Call for the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law.” It contains 13 requests including implementation of free medical care for A-bomb survivors.

September 1, 1968

The A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law goes into effect, bringing additional benefits to survivors.

March 30, 1978

The Supreme Court upholds the decision made in the first and second hearings of the Son Jin Doo case, ruling: “The Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law is based on the idea of national reparations.” The Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate is approved for survivors living overseas.

May 22, 1978

Nihon Hidankyo sends delegates to the first United Nations Special Session on Disarmament.

December 11, 1980

“The Informal Gathering to Discuss Fundamental Problems of the Atomic Bomb Survivors,” a private advisory body to the Minister of Health and Welfare, submits an opinion on relief measures for A-bomb survivors. An unfavorable view, concerning the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law, is taken on compensation by the government. Nihon Hidankyo issues a statement of protest.

March 25, 1982

For the first time, Nihon Hidankyo sends two A-bomb survivors to Europe to share their A-bomb accounts. This is part of the group’s effort called “A-bomb Storytellers’ Travels.”

November 17, 1984

Nihon Hidankyo issues its “Atomic Bomb Victims Demand.” “Never let there be Nuclear War! Ban Nuclear Weapons!” and “Enactment of a Hibakusha Aid Law” become the group’s two biggest demands.

December 9, 1994

The Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law is established by the coalition government including the Liberal Democratic Party and the Socialist Party. Focusing on relief measures for the A-bomb survivors, the law does not include government compensation and condolence to the A-bomb victims. It goes into effect on July 1, 1995.

April 17, 2003

Class action lawsuits on the A-bomb disease certification system begin.

March 17, 2008

After losing several class action lawsuits consecutively, a screening committee of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare mitigates the certification criteria. The ministry argues that certification for A-bomb survivors with diseases such as cancer is promptly granted if applicants meet certain conditions.

August 6, 2009

The Japanese government and Nihon Hidakyo reach a resolution to the series of class action lawsuits. Plaintiffs who won their first trials are certified. Plaintiffs who lost their cases are also aided.

December 1, 2009

A law is established in which the government subsidizes a fund for paying settlement money to plaintiffs who lost their class action lawsuits.

June 8, 2011

Nihon Hidankyo seeks amendments to the current Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law.

March 27, 2012

19 A-bomb survivors (two of them represented by family members due to their deaths), whose applications for A-bomb disease certification were rejected by the government after the certification criteria was revised in 2008, file a lawsuit to overturn the decision.

September 6, 2012

A committee of second-generation survivors is formed within Nihon Hidankyo.

August 5, 2014

A national association for A-bomb survivors who experienced the atomic bombing while in their mother’s womb is formed in Hiroshima.

May 27, 2016

President Obama visits Hiroshima. Three representatives of Nihon Hidankyo are invited to the ceremony connected to his visit.

(Originally published on July 31, 2016)

by Michiko Tanaka and Hidetoshi Arioka, Staff Writers

According to a survey conducted by the Chugoku Shimbun, nearly 90% of the groups of A-bomb survivors in five prefectures in the Chugoku region and the prefectural A-bomb survivors’ groups in other parts of Japan view U.S. President Barack Obama’s visit to Hiroshima in May positively. At the same time, the respondents of the groups expressed some dissatisfaction because Mr. Obama failed to make any concrete proposals for advancing nuclear disarmament in his “Hiroshima Speech,” and he avoided apologizing for the atomic bombings carried out by the United States. The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo), the only national group of A-bomb survivors, marks its 60th anniversary on August 10. Now, with key figures in the survivors’ movement, which seeks to prevent more sufferers of nuclear weapons, advancing in age, their urgent hope is that a world without nuclear arms can be realized as soon as possible.

Impressions of President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima

How do A-bomb survivors feel about President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima on May 27? In all, 105 out of 115 groups responded to this question in the survey. The respondents of 94 groups (89.5%) said that “it was very meaningful” or “it was reasonably meaningful,” indicating broad support for the first-ever visit to the A-bombed city by a sitting American president.

President Obama was present in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park for 52 minutes. When asked for reasons to account for their evaluation of his visit (multiple choices were allowed), the respondents of 75 groups, or 70% of the groups expressing a favorable assessment of the visit, chose the option “He offered flowers at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims and mourned the victims.” It seems the president’s act of laying a wreath of white flowers and pausing for five seconds, eyes closed, in front of the cenotaph, was a potent appeal to the survivors’ emotions.

In the comments section of the survey, the respondents also pointed to the significance of Mr. Obama’s visit. For example, the comment from a group of A-bomb survivors in Miyagi Prefecture said, “It was meaningful that he delivered a message from the A-bombed city to the world,” and a survivors’ group in Tottori Prefecture commented, “His visit has made it easier for leaders of other nations to visit the A-bombed cities.”

The respondents of more than 40 groups also looked favorably on President Obama’s interactions with two A-bomb survivors who were invited to attend the event, Sunao Tsuboi, 91, the co-chair of Nihon Hidankyo, and Shigeaki Mori, 79, a local historian, as well as the president’s visit to the Peace Memorial Museum to see a special exhibition featuring personal effects of the victims and photos showing the devastated city in the aftermath of the atomic bombing.

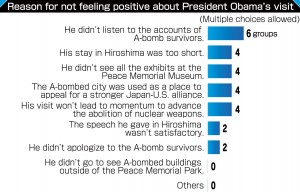

Meanwhile, only eight groups were pleased with President Obama’s 17-minute speech. There were a few favorable comments about the address, like this comment from a group in Yamanashi Prefecture: “He was in a difficult position, considering U.S. public opinion justifies the atomic bombings, and he worded the speech as best he could.” However, the respondents of 10 groups were disturbed by the opening sentence in the president’s speech--“Seventy-one years ago, on a bright cloudless morning, death fell from the sky and the world was changed”--because they felt this showed no sense of responsibility, as the head of the nation which dropped the atomic bombs.

The respondents of some groups also faulted the speech for not including a concrete vision or measures to advance the aim of nuclear abolition. After the speech Mr. Obama made in Prague in April 2009, when he articulated comprehensive ideas for addressing nuclear issues and which had a large impact on A-bomb survivors, they seem to feel that his speech in Hiroshima fell short as a message made from the A-bombed city.

The respondents of several groups said, in the comments section, that they would redouble their efforts in reaction to the president’s visit. The group in Hiroshima indicated their resolve by including their next concrete steps. The respondent of the group said that they plan to take part in the global signature drive led by Nihon Hidankyo and send letters to the leaders of the nuclear weapon states with references to President Obama’s speech.

Survivors feel torn over question of apologizing for A-bombings

While in Hiroshima, Mr. Obama offered no words of apology to the A-bomb survivors. The Chugoku Shimbun survey asked whether or not an American president should apologize when visiting the A-bombed cities in the future. Of the 105 groups asked, 32 groups said “Yes” and 38 said “No,” with 30 groups responding “I can’t say either way.” These three answers, equally split, convey the complex emotions of the survivors. The remaining five groups made no selection.

The respondents of the groups seeking an apology from the president stress U.S. responsibility for the inhumane suffering wrought by the atomic bombing. A group in Fukushima Prefecture commented, “Many innocent people, including non-combatants, were killed or injured in the atomic bombings,” while a group in Ishikawa Prefecture said, “Poor health stemming from A-bomb radiation, or anxiety about their health, has been the inheritance of second- and third-generation A-bomb survivors.”

Meanwhile, groups in Akitakata and Mukaihara said, “Rather than receiving an apology about the past, if the president takes concrete action for the future, to advance nuclear abolition, that would be the most significant atonement for us.” As this comment indicates, the respondents of the group who said that no apology from the president was required nevertheless expressed their hopes that the president, as the head of the nuclear superpower, would exercise leadership to realize the abolition of nuclear arms, the deep desire of A-bomb survivors.

As for the groups who said “I can’t say either way,” they said that it was too late to receive an apology, 71 years after the atomic bombings, and that Japan holds its share of responsibility for having undertaken the attack on Pearl Harbor.

70% have felt anger toward the United States

When they were surveyed about their feelings toward the United States, the country that dropped the atomic bombs, 100 groups responded. Of this number, 36 groups said, “I still feel angry” while 34 groups answered, “I used to feel angry,” totaling 70%.

Notably, there were respondents who described their emotions as a result of losing family members or friends. The respondent of a group in Fukuoka Prefecture commented, “My elder sister died in the atomic bombing at the age of 14. It’s unforgivable that innocent people were killed,” and the respondent of a group in the towns of Sera and Seranishi said, “My three siblings were killed in the atomic bombing. I will never forget that horror.” Also, a respondent of a group in the area of Ube, Sanyo, and Ononda reflected on the past and wrote, “Because my health was poor for a while, I felt angry about the atomic bombing back then, wondering what the war was all about and why this had happened to me.”

Meanwhile, the respondents of 13 groups said that they did not feel anger toward the United States. The respondent of a group in Tochigi Prefecture commented, “It was a war so both nations are to blame. The origin of our movement is our wish that the generations which follow will never have to experience the same suffering.” For this survey question, the respondents of 17 groups chose to answer, “I can’t say either way.”

Strengthening their appeal for nuclear abolition, in and out of Japan

On April 27, one month prior to President Obama’s visit to Hiroshima, a member of Nihon Hidankyo appealed to the people streaming past in front of JR Shibuya Station in Shibuya Ward, Tokyo, calling, “I don’t want anyone else to suffer what I’ve experienced. Could you please help by signing our petition?”

In March, Nihon Hidankyo proposed a global signature drive that calls for a nuclear weapons convention to ban and eliminate the earth’s nuclear arms. In the international community, nations which don’t possess or rely on nuclear weapons have been strengthening their efforts to have them banned, based on their inhumane impact. In response to this movement, the aging A-bomb survivors have been making a stronger appeal to people in Japan and overseas.

Since it was established on August 10, 1956, Nihon Hidankyo has been resolved to reach out to the international community. In the declaration made at its founding, titled “Message to the World,” the group vowed to help save humanity from the perils of nuclear weapons through the lessons learned from the survivors’ experiences. Representatives of the group have been dispatched abroad on many occasions.

Unfortunately, during the Cold War era, a number of countries, particularly the United States and the Soviet Union, engaged in an escalating arms race. Today, there are still more than 15,000 nuclear weapons in the world. The Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), which was enacted in 1970, permits the five main nuclear powers to possess nuclear arms yet obliges them to work toward nuclear disarmament. However, very little progress in this direction has been made to date. Nihon Hidankyo has been sending delegations to the NPT Review Conference, held every five years, where all the nations that have ratified the NPT gather to discuss actions for nuclear disarmament. But the collapse of the recent Review Conference, held in 2015, was deeply disappointing to them.

As of the end of this past March, the average age of the A-bomb survivors is 80.86. With an increasing number of people becoming aware of the inhumanity of nuclear weapons, the survivors are receiving more frequent requests to share their A-bomb accounts at international conferences. But because of their advancing age, the “younger” survivors, who actually have no memory of that time because they experienced it in early childhood, must often step in to fulfill these requests.

Toshiki Fujimori, 72, the assistant secretary general of Nihon Hidankyo, spoke about his A-bomb experience at a meeting of the U.N. working group on nuclear disarmament, which took place in Geneva, Switzerland in May. “My story may be less vivid than an account from an older survivor who has clear memories of the atomic bombing,” he said. “But I think I can share my experience and my feelings with listeners, since my mother and others told me all about what happened.”

Seeking to help sway the world toward nuclear abolition, the A-bomb survivors continue to exert themselves in Japan and out among the international community.

Groups seek to share A-bomb accounts more frequently

Surveyed about their activities for the future (multiple choices were allowed), 115 groups offered responses. The largest number of respondents, from 75 groups (65.2% of the total), chose “Sharing A-bomb survivors’ accounts of the atomic bombings at schools and in the community.” The percentage for this question rose by 5.7 points compared to the percentage for the same question asked by the Chugoku Shimbun in a survey last year to mark the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing. This indicates the desire of A-bomb survivors to hand down the reality of the bombings to the next generations by persevering in their efforts to share their experiences.

In addition, the respondents of 67 groups (58.3%) selected “Maintaining the health and friendship of our members,” while 56 groups (48.7%) said “Actions like a signature drive and sit-ins to advance the abolition of nuclear weapons.” These answers, too, earned slightly higher percentages than in last year’s survey. The survivors’ resolve to support one another and work for nuclear disarmament remains strong.

The respondents of 53 groups (46.1%) also chose “Actions to strengthen relief measures by the government, such as free health check-ups for second-generation survivors,” putting emphasis on providing support for second-generation survivors, who will assume greater responsibility for the groups’ activities in the future. Also selected, by 52 groups (45.2%), was “Maintaining monuments and memorial services,” which indicates that the survivors wish to continue mourning the victims even if their groups become inactive due to their advancing age.

Groups continue their efforts to expand relief measures

The A-bomb survivors endured “the lost decade” after the atomic bombings. During this time they were forced to face their hardships alone because there were virtually no avenues of public or private support. These conditions changed, though, in March 1954, when the crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat, were exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll. As the movement to ban A- and H-bombs started to spread, the A-bomb survivors began making their voices heard.

In 1957, the Japanese government started issuing the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate and covering the costs of treatment for A-bomb-related diseases. These first relief measures have since been changed dozens of times over the years as Nihon Hidakyo pursued efforts that included sit-ins, marches, and petitions to the Japanese Diet. For instance, in 1968, the government began providing a number of new benefits to A-bomb survivors, including a health management allowance.

However, the group’s greatest desire, that the Japanese government compensate the sufferers for radiation damage caused by the atomic bombs, has not yet materialized. The group holds the basic conviction that forcing the government to compensate for the damages caused by the atomic bombings, which were brought on by the war Japan waged, will lead to the goal of no more nuclear sufferers. The government, though, has continued to rebuff the idea of providing compensation to the A-bomb survivors, contending that the population must endure the sacrifices of war equally.

Meanwhile, lawsuits over the government’s authorization of A-bomb diseases continue in Japanese courts. Nihon Hidankyo has demanded that the government establish a new allowance system, which could increase the amount of allowance in line with each survivor’s symptoms, thus abandoning the current certification system, which has enabled the government to make judgments based on a defined standard of diseases and conditions. The Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has not met this request, however, arguing that the current standard, created after a series of discussions, is valuable.

Secretary general of Nihon Hidankyo wants President Obama’s visit to inspire action

The Chugoku Shimbun spoke with Terumi Tanaka, 84, the secretary general of Nihon Hidankyo, about his thoughts on the survey results and the challenges that lie ahead. Below are his comments.

The A-bomb survivors have had high hopes for President Obama, who has advocated “a world without nuclear weapons.” Even if some survivors are not fully satisfied by his words and actions in Hiroshima, they may look favorably on his visit, considering that his actions in Hiroshima were likely restrained by the conditions in his own nation.

What really matters are concrete efforts to realize the abolition of nuclear arms. In his speech, President Obama didn’t offer any specific measures for advancing nuclear disarmament. Along with the fact that he avoided the question of U.S. responsibility for dropping the atomic bombs, we plan to make use of the issues raised by his visit to pursue further efforts in the future.

Because of the hard reality that younger people will need to take over our activities, we must familiarize them not only with the devastation caused by the bombings but also with the progress made by the survivors’ movement, including our thoughts and feelings, our aims and actions, and the goals that must still be fulfilled. We have been putting all this down in documents that can be used for reference. I hope the younger generations will understand the spirit of our movement and carry on with our initiatives in their own way.

Nuclear weapons have not yet been eliminated because this is a problem that concerns us all, not only the A-bomb survivors. We launched a global signature drive to lend support to the movement which seeks to create a legal ban on nuclear arms because we feel a sense of crisis that nothing will change if simply left up to the actions of politicians. Through our efforts, we want to provide the opportunity for citizens in the nuclear nations to consider this issue more carefully.

Highlights of the movement by A-bomb survivors and Nihon Hidankyo

August 6, 1945

The United States drops the the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima. A second atomic bomb is dropped on Nagasaki on August 9.

August 27, 1951

Kiyoshi Kikkawa and about 20 A-bomb survivors form the Rehabilitation Group for A-bomb Survivors.

August 10, 1952

Mr. Kikkawa, poet Sankichi Toge, and about 50 A-bomb survivors establish the Atomic Bomb Survivors Association in Hiroshima.

March 1, 1954

The crew members of the Daigo Fukuryu Maru (The Lucky Dragon No. 5), a Japanese tuna fishing boat, are exposed to radioactive fallout from a U.S. hydrogen bomb test at Bikini Atoll.

August 6, 1955

The first World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs is held in Hiroshima.

September 19, 1955

The Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs (Gensuikyo) is established.

May 27, 1956

The Hiroshima Prefectural Confederation of A-bomb Sufferers Organizations is established.

August 10, 1956

The Japan Confederation of A- and H-Bomb Sufferers Organizations (Nihon Hidankyo) is established. The head office is placed in Hiroshima. Heiichi Fuji is elected secretary general.

March 25, 1957

A-bomb survivors stage a sit-in protest in front of the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, calling for a halt to hydrogen bomb tests by the United Kingdom.

April 1, 1957

The Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law comes into effect. The Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate begins to be issued to A-bomb survivors.

February 17, 1961

Nihon Hidankyo holds a gathering to petition the Diet for the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law. The group makes its first march from Hibiya to Shinbashi.

August 5, 1963

The 9th World Conference Against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs faces disarray among the participants.

February 1, 1965

13 groups including the General Council of Trade Unions establish the Japan Congress against A- and H- Bombs (Gensuikin).

November 1, 1965

The Ministry of Health and Welfare conducts the first nationwide fact-finding survey of A-bomb survivors.

October 15, 1966

Nihon Hidankyo releases “Characteristics of the A-bomb Damage and the Call for the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law.” It contains 13 requests including implementation of free medical care for A-bomb survivors.

September 1, 1968

The A-bomb Survivors Special Measures Law goes into effect, bringing additional benefits to survivors.

March 30, 1978

The Supreme Court upholds the decision made in the first and second hearings of the Son Jin Doo case, ruling: “The Atomic Bomb Medical Relief Law is based on the idea of national reparations.” The Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate is approved for survivors living overseas.

May 22, 1978

Nihon Hidankyo sends delegates to the first United Nations Special Session on Disarmament.

December 11, 1980

“The Informal Gathering to Discuss Fundamental Problems of the Atomic Bomb Survivors,” a private advisory body to the Minister of Health and Welfare, submits an opinion on relief measures for A-bomb survivors. An unfavorable view, concerning the Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law, is taken on compensation by the government. Nihon Hidankyo issues a statement of protest.

March 25, 1982

For the first time, Nihon Hidankyo sends two A-bomb survivors to Europe to share their A-bomb accounts. This is part of the group’s effort called “A-bomb Storytellers’ Travels.”

November 17, 1984

Nihon Hidankyo issues its “Atomic Bomb Victims Demand.” “Never let there be Nuclear War! Ban Nuclear Weapons!” and “Enactment of a Hibakusha Aid Law” become the group’s two biggest demands.

December 9, 1994

The Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law is established by the coalition government including the Liberal Democratic Party and the Socialist Party. Focusing on relief measures for the A-bomb survivors, the law does not include government compensation and condolence to the A-bomb victims. It goes into effect on July 1, 1995.

April 17, 2003

Class action lawsuits on the A-bomb disease certification system begin.

March 17, 2008

After losing several class action lawsuits consecutively, a screening committee of the Ministry of Health, Labor, and Welfare mitigates the certification criteria. The ministry argues that certification for A-bomb survivors with diseases such as cancer is promptly granted if applicants meet certain conditions.

August 6, 2009

The Japanese government and Nihon Hidakyo reach a resolution to the series of class action lawsuits. Plaintiffs who won their first trials are certified. Plaintiffs who lost their cases are also aided.

December 1, 2009

A law is established in which the government subsidizes a fund for paying settlement money to plaintiffs who lost their class action lawsuits.

June 8, 2011

Nihon Hidankyo seeks amendments to the current Atomic Bomb Survivors Relief Law.

March 27, 2012

19 A-bomb survivors (two of them represented by family members due to their deaths), whose applications for A-bomb disease certification were rejected by the government after the certification criteria was revised in 2008, file a lawsuit to overturn the decision.

September 6, 2012

A committee of second-generation survivors is formed within Nihon Hidankyo.

August 5, 2014

A national association for A-bomb survivors who experienced the atomic bombing while in their mother’s womb is formed in Hiroshima.

May 27, 2016

President Obama visits Hiroshima. Three representatives of Nihon Hidankyo are invited to the ceremony connected to his visit.

(Originally published on July 31, 2016)