Survivors’ Stories: Ichie Okada, 80, Nishi Ward, Hiroshima

Mar. 21, 2016

Shocked by sight of the wounded fleeing past

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

Ichie Okada (née Ikushima), 80, lost her mother to tuberculosis shortly after she was born and her father in the year following the atomic bombing. Her grandmother, who took care of her after that, died when she was in junior high school, and she then decided to live independently. She began working full-time and worked for the same company until she retired, even after getting married and having children, which was rare for a woman back then. She has long done her best to keep smiling each day.

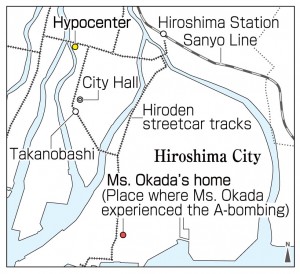

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Okada was nine years old and in fourth grade at Ujina National School (now Ujina Elementary School in Minami Ward). In April 1945, she was evacuated, along with other children, to a temple in the village of Sakugi (now part of Miyoshi City) in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture. Such evacuations of children were taking place over fears of air raids on the city of Hiroshima. She remembers that people in the village were kind to them and that she enjoyed eating mulberries, which stained her mouth and hands purple. Still, she wanted to return to her home, and when her grandmother, Sumi, suffered a brain hemorrhage in July, she returned to her house in Ujinakanda (now part of Minami Ward), about 4.1 kilometers from the hypocenter.

When the atomic bomb exploded, she was at home. She recalled, “There was a blinding flash, and an enormous roar and blast, but the windows didn’t break because strips of paper had been affixed to them diagonally.”

On the road in the front of their house, people came walking along the streetcar tracks, fleeing south toward Ninoshima Island (now part of Minami Ward). “Some people, their burnt skin was peeling and dangling down from their body, and others had burned backs,” she recalled. “My grandmother told me not to look at them.”

That morning, her uncle had gone out to help with the war effort by tearing down homes to create a fire lane in the vicinity of City Hall, taking the place of her father, Susume, who was not feeling well. Her uncle did not return. Her father went searching for him, but was unable to go beyond Takano Bridge because of raging flames. On August 9, her uncle finally returned home, without bad burns, yet died that night. In November of the following year, her father died of intestinal tuberculosis. Ms. Okada said, “My father’s ears and nose were bleeding. It may have been the result of his exposure to the A-bomb’s radiation.”

After the war, the A-bomb survivors faced prejudice, including the rumor that they would not be able to have children. In 1948, when her grandmother filled in a form about the members of the family who were at home at the time of the atomic bombing, and submitted it to City Hall, she did not include Ms. Okada’s name. Ms. Okada explained, “My grandmother was worried about whether or not I would be able to get married.”

Her grandmother died in 1950. After that, Ms. Okada decided she would work and live on her own. In the spring of 1954, after graduating from high school, she began working at Fukuya department store (now part of Naka Ward). This was soon after the sugar control act was abolished and she was assigned to the food floor. Looking back at that time, she said, “Amanatto, sugared red beans, and yakkoarare, roasted mochi pieces sweetened with sugar, sold very well.”

She married a man who was introduced to her by an acquaintance. He agreed to her condition that he let her continue working. In those days, there was no system of childcare leave. Fumiko, her mother-in-law, took care of her eldest son, Kazuya. Ms. Okada finally retired from Fukuya department store at the age of 60 and looked after her husband until he died seven years ago. At around the same time, a tumor was found in her kidney, and she underwent an operation to remove it. She thinks it may have been caused by the atomic bombing.

She now enjoys doing folk dance every day. She believes, “Peace is a very good thing because it enables us to do what we want to do. Those who know war, like us, must convey our experiences and continue calling for peace.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

A-bombing reshaped people’s lives

Ms. Okada’s grandmother did not add her name to the notice she submitted to City Hall because the fact that she experienced the atomic bombing could have affected her chances of getting married. For this reason, it took about a year for her to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. I learned that the atomic bombing reshaped people’s lives. I plan to relate her story, along with her opposition to nuclear weapons and war, in peace activities at school, including guiding people on tours of A-bomb monuments. (Chiaki Yamada, 16)

Creating a world of secure employment

Ms. Okada lost her parents early in her life. I was impressed how she decided to be self-reliant and continued working until she retired, since this was at a time when there was no system of childcare leave. She was fortunate to have good colleagues and she worked there for many years. But her cousin, who began working for another company, was laid off three years after joining the company. I want to help create a world where everyone has secure employment. (Maiko Hanaoka, 17)

War forces civilians to endure

Ms. Okada felt the gap between soldiers and civilians when she learned that snacks were stored in a military warehouse in her neighborhood. The public was hungry because of the war. It’s not only soldiers that are affected. Civilians, too, are forced to endure the fighting, but they don’t benefit at all. This should be stressed. (Kohei Hayashi, 17)

(Originally published on March 21, 2016)

by Rie Nii, Staff Writer

Ichie Okada (née Ikushima), 80, lost her mother to tuberculosis shortly after she was born and her father in the year following the atomic bombing. Her grandmother, who took care of her after that, died when she was in junior high school, and she then decided to live independently. She began working full-time and worked for the same company until she retired, even after getting married and having children, which was rare for a woman back then. She has long done her best to keep smiling each day.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Okada was nine years old and in fourth grade at Ujina National School (now Ujina Elementary School in Minami Ward). In April 1945, she was evacuated, along with other children, to a temple in the village of Sakugi (now part of Miyoshi City) in the northern part of Hiroshima Prefecture. Such evacuations of children were taking place over fears of air raids on the city of Hiroshima. She remembers that people in the village were kind to them and that she enjoyed eating mulberries, which stained her mouth and hands purple. Still, she wanted to return to her home, and when her grandmother, Sumi, suffered a brain hemorrhage in July, she returned to her house in Ujinakanda (now part of Minami Ward), about 4.1 kilometers from the hypocenter.

When the atomic bomb exploded, she was at home. She recalled, “There was a blinding flash, and an enormous roar and blast, but the windows didn’t break because strips of paper had been affixed to them diagonally.”

On the road in the front of their house, people came walking along the streetcar tracks, fleeing south toward Ninoshima Island (now part of Minami Ward). “Some people, their burnt skin was peeling and dangling down from their body, and others had burned backs,” she recalled. “My grandmother told me not to look at them.”

That morning, her uncle had gone out to help with the war effort by tearing down homes to create a fire lane in the vicinity of City Hall, taking the place of her father, Susume, who was not feeling well. Her uncle did not return. Her father went searching for him, but was unable to go beyond Takano Bridge because of raging flames. On August 9, her uncle finally returned home, without bad burns, yet died that night. In November of the following year, her father died of intestinal tuberculosis. Ms. Okada said, “My father’s ears and nose were bleeding. It may have been the result of his exposure to the A-bomb’s radiation.”

After the war, the A-bomb survivors faced prejudice, including the rumor that they would not be able to have children. In 1948, when her grandmother filled in a form about the members of the family who were at home at the time of the atomic bombing, and submitted it to City Hall, she did not include Ms. Okada’s name. Ms. Okada explained, “My grandmother was worried about whether or not I would be able to get married.”

Her grandmother died in 1950. After that, Ms. Okada decided she would work and live on her own. In the spring of 1954, after graduating from high school, she began working at Fukuya department store (now part of Naka Ward). This was soon after the sugar control act was abolished and she was assigned to the food floor. Looking back at that time, she said, “Amanatto, sugared red beans, and yakkoarare, roasted mochi pieces sweetened with sugar, sold very well.”

She married a man who was introduced to her by an acquaintance. He agreed to her condition that he let her continue working. In those days, there was no system of childcare leave. Fumiko, her mother-in-law, took care of her eldest son, Kazuya. Ms. Okada finally retired from Fukuya department store at the age of 60 and looked after her husband until he died seven years ago. At around the same time, a tumor was found in her kidney, and she underwent an operation to remove it. She thinks it may have been caused by the atomic bombing.

She now enjoys doing folk dance every day. She believes, “Peace is a very good thing because it enables us to do what we want to do. Those who know war, like us, must convey our experiences and continue calling for peace.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

A-bombing reshaped people’s lives

Ms. Okada’s grandmother did not add her name to the notice she submitted to City Hall because the fact that she experienced the atomic bombing could have affected her chances of getting married. For this reason, it took about a year for her to obtain the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate. I learned that the atomic bombing reshaped people’s lives. I plan to relate her story, along with her opposition to nuclear weapons and war, in peace activities at school, including guiding people on tours of A-bomb monuments. (Chiaki Yamada, 16)

Creating a world of secure employment

Ms. Okada lost her parents early in her life. I was impressed how she decided to be self-reliant and continued working until she retired, since this was at a time when there was no system of childcare leave. She was fortunate to have good colleagues and she worked there for many years. But her cousin, who began working for another company, was laid off three years after joining the company. I want to help create a world where everyone has secure employment. (Maiko Hanaoka, 17)

War forces civilians to endure

Ms. Okada felt the gap between soldiers and civilians when she learned that snacks were stored in a military warehouse in her neighborhood. The public was hungry because of the war. It’s not only soldiers that are affected. Civilians, too, are forced to endure the fighting, but they don’t benefit at all. This should be stressed. (Kohei Hayashi, 17)

(Originally published on March 21, 2016)