Survivors’ Stories: Hiroko Kimura 80, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima

Oct. 3, 2016

Suffered poor health in the month that followed A-bombing

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

When Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb, Hiroko Kimura (née Shimonaka), 80, was a fourth grader at Hesaka National School (now Hesaka Elementary School in Higashi Ward). She was out in the schoolyard when the bomb exploded. For the following month, Ms. Kimura felt ill, even when she was sitting or lying on her bed. “I was worried because the cause of my poor health couldn’t be determined,” she said. Now, however, she suspects that her condition was the result of radiation sickness when she was exposed to the atomic bomb. She was able to recover better health, though, without receiving any medical treatment. But the situation in Fukushima Prefecture, where the accident at the nuclear power plant released radiation and spread contamination, has saddened her. “Nuclear power and human beings can’t coexist on the earth,” she said firmly.

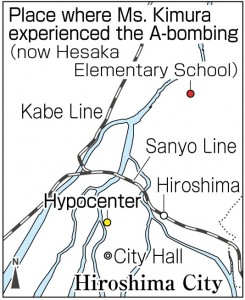

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Kimura, who was nine years old at the time, had gathered with other students on the schoolyard to help with the war effort: cutting grass to feed military horses. But during the morning assembly, an older student suddenly shouted, “A B-29 is coming!” As soon as the plane flew over the mountain behind her, there was a flash in the sky. Ms. Kimura felt herself enveloped by a dazzling light, something she had never experienced before, then heard an enormous roar. She rushed into an air raid shelter with the others.

When the gathering broke up soon after, she turned to go home, but couldn’t find her sickle. Worried that her grandmother might scold her for losing it, she headed back to the house, which was located about 5.1 kilometers from the hypocenter. When she arrived, she found that the windows and sliding doors were broken, and the mosquito netting around the beds had been blown off. Tatsu, her grandmother, was relieved that she had made it home safely.

Many survivors fled from the city center to the outlying area of Hesaka. From the day after the bombing, her family cared for three wounded soldiers at their house. One of them suffered severe burns to his back, and her grandmother removed the maggots that wriggled in his wounds. Around the middle of August, the soldiers were gone, but Ms. Kimura isn’t sure if relatives came for them and took them home, or if they died. Sakayo, her mother, helped daily with the grim task of cremating the victims. The area was filled with the stench of bodies being burned.

After the bombing, Ms. Kimura didn’t feel well and a neighbor told her she was suffering from malnutrition. But of the five children in her family, she was the only one who developed such symptoms. She said, “I didn’t think my neighbor was right, because I had regularly been eating the rice we grew in our field.” It was also a mystery how the stalks of rice in their field turned brown after the bombing. She was worried that the rice might not be ready to harvest in autumn, but the color of the plants became green again. In the end, her family was able to harvest the rice.

On August 9, when Ms. Kimura went to school to look after the rabbits kept there, she saw a boy who was around her age. He had been brought there because the school was made a temporary outpost for the Army Hospital. The boy was badly burned and pleaded to a soldier for water. But Ms. Kimura was unable to do anything for him.

After her condition improved, she helped on the family farm because Jitsuo, her father, had died of illness in the fall of the previous year. In fifth and sixth grade, she would go to the city center with her mother to collect human waste, then use this as fertilizer for their rice and vegetable fields.

She recalled the difficult state of the city after the atomic bombing, with people living in shacks and subsisting through the black markets that sprang up. People were working hard to survive, and by seeing how everyone else was enduring hardships, she was able to labor on in the fields.

When her mother asked for her help in making ends meet, Ms. Kimura gave up the idea of going on to high school. So after finishing junior high, she began working and put her monthly wages toward supporting the family. The amount totaled 3,000 yen, less 500 yen for a train pass. She made this sacrifice because she felt that it was her duty, standing in for her father, to enable her two younger sisters to go to high school. Her mother applied for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate for all five children, collectively, contending that they were exposed to radiation while caring for A-bomb survivors. Ms. Kimura received her certificate in 1960.

That year, she also married her husband, Meiji. He is an A-bomb survivor, too, and is now 82. They were blessed with three children, but when Shinji, their eldest son, died of a heart attack in 2010 at the age of 46, they wondered if his death was somehow connected to the fact that they had both experienced the atomic bombing.

This article marked the first time Ms. Kimura has recounted her A-bomb experience. She decided to share her account after reading an article in the newspaper in February of this year. The article was about Shuntaro Hida, a doctor who experienced the bombing while in Hesaka. Ms. Kimura was encouraged by the fact that Dr. Hida continued to speak out about the horror of A-bomb radiation, even after turning 99. She said, “This anxiety about exposure to radiation extends into younger generations. We must never wage a tragic war like that again.” She now hopes to share her experience with many more people.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Must pass on sad memories to others

It’s not easy to forget sad memories. Even now, when Ms. Kimura sees lights at night, it reminds her of the searchlights she saw during the war. I also feel sad when I see a TV program that shows the death of a pet because I lost my dog, who was 16, three years ago. I want to continue taking in the feelings of the survivors, who have faced hardships for 71 years, and convey their experiences to others. (Kotoori Kawagishi, 14)

Destructive power of nuclear weapons is beyond imagination

The Hesaka area, where Ms. Kimura lived at the time of the atomic bombing, is more than five kilometers from the hypocenter and is protected by mountains. Still, she told us that the sliding doors and shoji screens of their home were blown down by the bomb blast, which enabled me to again appreciate how destructive the atomic bomb was. Though the model of the “Little Boy” atomic bomb that’s on display in the Peace Memorial Museum seems relatively small, the blast it produced actually had a far-ranging impact. The power of nuclear weapons is beyond our imagination. (Harumi Okada, 17)

Impressed with her strength to endure hard times

Ms. Kimura told us that she felt sad when she saw the boy with severe burns asking the soldier for water. It must have been really hard for a girl in fourth grade to see first-hand so many people in pain and suffering. As a child, the smell of the bodies being cremated must have been a shock, too. I was very impressed with the strength she displayed to overcome her distress, work in the fields, and support her family. (Mei Morimoto, 18)

(Originally published on October 3, 2016)

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

When Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb, Hiroko Kimura (née Shimonaka), 80, was a fourth grader at Hesaka National School (now Hesaka Elementary School in Higashi Ward). She was out in the schoolyard when the bomb exploded. For the following month, Ms. Kimura felt ill, even when she was sitting or lying on her bed. “I was worried because the cause of my poor health couldn’t be determined,” she said. Now, however, she suspects that her condition was the result of radiation sickness when she was exposed to the atomic bomb. She was able to recover better health, though, without receiving any medical treatment. But the situation in Fukushima Prefecture, where the accident at the nuclear power plant released radiation and spread contamination, has saddened her. “Nuclear power and human beings can’t coexist on the earth,” she said firmly.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Kimura, who was nine years old at the time, had gathered with other students on the schoolyard to help with the war effort: cutting grass to feed military horses. But during the morning assembly, an older student suddenly shouted, “A B-29 is coming!” As soon as the plane flew over the mountain behind her, there was a flash in the sky. Ms. Kimura felt herself enveloped by a dazzling light, something she had never experienced before, then heard an enormous roar. She rushed into an air raid shelter with the others.

When the gathering broke up soon after, she turned to go home, but couldn’t find her sickle. Worried that her grandmother might scold her for losing it, she headed back to the house, which was located about 5.1 kilometers from the hypocenter. When she arrived, she found that the windows and sliding doors were broken, and the mosquito netting around the beds had been blown off. Tatsu, her grandmother, was relieved that she had made it home safely.

Many survivors fled from the city center to the outlying area of Hesaka. From the day after the bombing, her family cared for three wounded soldiers at their house. One of them suffered severe burns to his back, and her grandmother removed the maggots that wriggled in his wounds. Around the middle of August, the soldiers were gone, but Ms. Kimura isn’t sure if relatives came for them and took them home, or if they died. Sakayo, her mother, helped daily with the grim task of cremating the victims. The area was filled with the stench of bodies being burned.

After the bombing, Ms. Kimura didn’t feel well and a neighbor told her she was suffering from malnutrition. But of the five children in her family, she was the only one who developed such symptoms. She said, “I didn’t think my neighbor was right, because I had regularly been eating the rice we grew in our field.” It was also a mystery how the stalks of rice in their field turned brown after the bombing. She was worried that the rice might not be ready to harvest in autumn, but the color of the plants became green again. In the end, her family was able to harvest the rice.

On August 9, when Ms. Kimura went to school to look after the rabbits kept there, she saw a boy who was around her age. He had been brought there because the school was made a temporary outpost for the Army Hospital. The boy was badly burned and pleaded to a soldier for water. But Ms. Kimura was unable to do anything for him.

After her condition improved, she helped on the family farm because Jitsuo, her father, had died of illness in the fall of the previous year. In fifth and sixth grade, she would go to the city center with her mother to collect human waste, then use this as fertilizer for their rice and vegetable fields.

She recalled the difficult state of the city after the atomic bombing, with people living in shacks and subsisting through the black markets that sprang up. People were working hard to survive, and by seeing how everyone else was enduring hardships, she was able to labor on in the fields.

When her mother asked for her help in making ends meet, Ms. Kimura gave up the idea of going on to high school. So after finishing junior high, she began working and put her monthly wages toward supporting the family. The amount totaled 3,000 yen, less 500 yen for a train pass. She made this sacrifice because she felt that it was her duty, standing in for her father, to enable her two younger sisters to go to high school. Her mother applied for the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate for all five children, collectively, contending that they were exposed to radiation while caring for A-bomb survivors. Ms. Kimura received her certificate in 1960.

That year, she also married her husband, Meiji. He is an A-bomb survivor, too, and is now 82. They were blessed with three children, but when Shinji, their eldest son, died of a heart attack in 2010 at the age of 46, they wondered if his death was somehow connected to the fact that they had both experienced the atomic bombing.

This article marked the first time Ms. Kimura has recounted her A-bomb experience. She decided to share her account after reading an article in the newspaper in February of this year. The article was about Shuntaro Hida, a doctor who experienced the bombing while in Hesaka. Ms. Kimura was encouraged by the fact that Dr. Hida continued to speak out about the horror of A-bomb radiation, even after turning 99. She said, “This anxiety about exposure to radiation extends into younger generations. We must never wage a tragic war like that again.” She now hopes to share her experience with many more people.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Must pass on sad memories to others

It’s not easy to forget sad memories. Even now, when Ms. Kimura sees lights at night, it reminds her of the searchlights she saw during the war. I also feel sad when I see a TV program that shows the death of a pet because I lost my dog, who was 16, three years ago. I want to continue taking in the feelings of the survivors, who have faced hardships for 71 years, and convey their experiences to others. (Kotoori Kawagishi, 14)

Destructive power of nuclear weapons is beyond imagination

The Hesaka area, where Ms. Kimura lived at the time of the atomic bombing, is more than five kilometers from the hypocenter and is protected by mountains. Still, she told us that the sliding doors and shoji screens of their home were blown down by the bomb blast, which enabled me to again appreciate how destructive the atomic bomb was. Though the model of the “Little Boy” atomic bomb that’s on display in the Peace Memorial Museum seems relatively small, the blast it produced actually had a far-ranging impact. The power of nuclear weapons is beyond our imagination. (Harumi Okada, 17)

Impressed with her strength to endure hard times

Ms. Kimura told us that she felt sad when she saw the boy with severe burns asking the soldier for water. It must have been really hard for a girl in fourth grade to see first-hand so many people in pain and suffering. As a child, the smell of the bodies being cremated must have been a shock, too. I was very impressed with the strength she displayed to overcome her distress, work in the fields, and support her family. (Mei Morimoto, 18)

(Originally published on October 3, 2016)