Gray area: Effects of exposure to low-level radiation, Part 4 [2]

Jun. 20, 2016

In a nuclear superpower: Workers face acute anxiety in shadow of U.S. nuclear policy

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

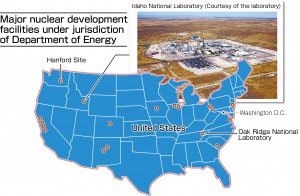

The United States, a nuclear superpower, fervently pursued nuclear research and development programs for both military and civilian use during the Cold War, when the nuclear arms race intensified between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union. Since the time of the Manhattan Project, workers at nuclear weapons-related facilities have been complaining of health problems resulting from radiation exposure through their ordinary course of work or from radiation leakage accidents. How many of those that work at facilities administered by the Department of Energy (DOE) have been recognized as having health problems because of their roles? Or are they being left unattended, without relief measures? Some efforts have been made to clarify this situation in the midst of the country’s pursuit of its nuclear policy.

Private company plays down plutonium contamination

At his home in Idaho Falls in eastern Idaho, Ralph Stanton, 51, expressed his outrage. According to this well-built former worker at the Idaho National Laboratory, he was told that his radiation exposure was not serious despite suffering plutonium contamination. He added, “Who will take responsibility if I get ill in 10 years?”

The Idaho National Laboratory has played an important role in U.S. nuclear research. The laboratory is administered by the DOE, but its operation was outsourced to a private business called BEA. Mr. Stanton and 15 other workers were involved in a plutonium contamination accident in November 2011 at a facility called ZPPR, which was used for fast reactor tests between the 1960s and 1992.

There was still a large amount of fuel called “clamshell” at the facility. The fuel was in metal containers that looked like two plates put together. The accident occurred when workers were taking out plutonium from those containers and putting it into others.

According to Mr. Stanton, those containers were at least 30 years old, and some of them were hot. Workers did not use glove boxes (airtight containers) but worktables similar to those used for salad bars at family restaurants. Efficiency was given the highest priority, he added.

His anxiety became a reality. One of the clamshells was made of plastic and it was wrapped with tape. He told the person in charge that something was clearly wrong. But the person did not take him seriously and ordered him to continue his work. He had no choice but to open the container. A worker next to him shouted, “Powder!” The plutonium was oxidized when it became exposed to the air and turned into pepper-like powder.

The alarm for the worktable was out of order, and there was a gap of time before another alarm several meters away went off. After fleeing, Mr. Stanton was told to take off his clothes but he was not allowed to shower there because the tank for contaminated water was said to be full. An industrial doctor detected americium 241, a radioactive substance, in Mr. Stanton’s lungs, which is considered evidence of the presence of plutonium. That night he vomited numerous times at home. But the next day, his boss flatly stated that his symptoms were caused by the flu.

His family was also affected by this problem. The Stantons had an expert examine his house on their own, and a small amount of plutonium was detected. As they could not afford to move to a new house, they had to clean up their house wearing gas masks. As they recalled this experience, Mr. Stanton’s wife Jodi, 47, sat beside him and wiped away tears.

In its investigative report on the accident, the DOE determined that security measures had been lacking and leveled a fine against BEA. Later, measures to prevent a recurrence were implemented.

But Mr. Stanton had nowhere to vent his anger. The company said that his exposure dose was 100 millirems (1 millisievert), a figure that he found not believable. If that was the case, the prospect of receiving compensation for the accident was dim. He demanded that the company disclose more information and maintained that his house had been contaminated, too, which resulted in a fierce clash with the company. He was fired with the contention that he had dozed off during work at the end of 2013. He then took legal action against BEA, claiming that what the company did was illegal and a reprisal against a whistle-blower.

Tami Thatcher is a former safety analyst at the DOE and now belongs to the Environmental Defense Institute, a civil organization that is supporting Mr. Stanton’s effort. She said that his case was a result of extremely sloppy management, but that in many cases the companies try to make such accidents look less serious.

While Mr. Stanton wrestles with anxiety over his health, he also acknowledged that work involving nuclear materials cannot be performed without the possibility of exposure to radiation.

Major newspaper group reports full picture of health damage

At the Idaho National Laboratory, three soldiers died when a core meltdown accident occurred at an Army test reactor in 1961. A local environmental organization points out that there is a large amount of radioactive waste at this site and that the soil and groundwater are contaminated.

Radioactive contamination is a nationwide problem. The Hanford Site in the state of Washington, where the plutonium for the Nagasaki bomb was produced, is dubbed the most polluted nuclear facility in the United States.

How many workers at nuclear facilities in this nation have been suffering from health problems? Surprisingly, the whole scope of this problem was not fully understood until recently. Even when workers are confident that they developed cancer or other diseases as a result of radiation exposure, there are difficult obstacles to overcome before they can sue the DOE or other parties, and many of them bear their suffering in silence.

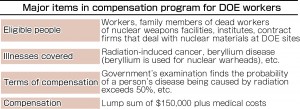

A change was brought about in 2000. The Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act (EEOICPA) was established by Congress, enabling workers to seek compensation without a trial.

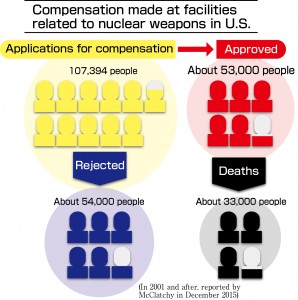

This caught the attention of the McClatchy Company, a major newspaper group. When the company requested the disclosure of related information, the U.S. government released 70 million items of electronic data on compensation applications. They analyzed the data, interviewed people linked to this issue, and reported the results through its 29 local newspapers. The company’s website provides an enormous amount of information on more than 100,000 people, including their diseases and whether they are still living or not.

At his office in Washington D.C., reporter Rob Hotakainen, said, “At least 33,488 people who were recognized as victims have died.” He added that the suffering of each person must be understood, not just the number of victims, and that the health damage has not ended even though security measures have been stepped up since the Cold War era.

The government had expected to spend 120 million dollars (12.4 billion yen) to compensate 3,000 people annually. But, in reality, 12 billion dollars (1.248 trillion yen) was spent in 14 years, which is seven times larger than estimated. Still, fewer than half the applicants can obtain compensation because it is difficult to prove that they suffered radiation exposure, depending on the exposure dose or on the facility where they worked.

The newspaper company questions the government’s attitude, saying, “The U.S. is planning to modernize its nuclear arsenal, spending one trillion dollars (104 trillion yen) in the future. Is the country learning any lessons from the suffering of these people?”

Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act established based on epidemiological surveys

The EEOICPA was established after the administration of then President Bill Clinton fully conceded that workers at U.S. nuclear-related facilities were suffering damage to their health. Congress also made clear that radioactive materials are extremely dangerous and even exposure to low doses of radiation can be medically harmful.

In addition to the complaints made by the victims, the results of many epidemiological surveys were respected. But survey results are not always consistent.

According to one research study conducted at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where the uranium used for the Hiroshima bomb was produced, the excess relative risk of dying from all types of cancer is 10 times that of A-bomb survivors, and the accumulation of exposure doses from the age of 45 and up can increase mortality risks. There is a counterargument that cancer deaths are mostly influenced by smoking. One study says that cancer cases increased even for those whose doses were within the safety standards, while another study shows a contrary result.

David Richardson, an associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, carried out an epidemiological survey at Oak Ridge. Dr. Richardson said we must be aware that, unlike nuclear power plants, workers at a facility where various materials are handled are suffering a complex form of contamination from both nuclear and other harmful substances.

Keywords

Idaho National Laboratory

The Idaho National Laboratory’s predecessor was opened in 1949. The laboratory has had 52 nuclear reactors on a site that is larger than Tokyo. Research is pursued on the nuclear fuel cycle, advanced nuclear reactors, nuclear non-proliferation technologies, and countermeasures against cyberattacks. The laboratory’s history is closely tied to military affairs. The nuclear reactor for nuclear-powered vessels was first developed at this laboratory. Spent fuel was reprocessed at this laboratory and was used to produce nuclear weapons at different facilities.

(Originally published on June 20, 2016)

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

The United States, a nuclear superpower, fervently pursued nuclear research and development programs for both military and civilian use during the Cold War, when the nuclear arms race intensified between the U.S. and the former Soviet Union. Since the time of the Manhattan Project, workers at nuclear weapons-related facilities have been complaining of health problems resulting from radiation exposure through their ordinary course of work or from radiation leakage accidents. How many of those that work at facilities administered by the Department of Energy (DOE) have been recognized as having health problems because of their roles? Or are they being left unattended, without relief measures? Some efforts have been made to clarify this situation in the midst of the country’s pursuit of its nuclear policy.

Private company plays down plutonium contamination

At his home in Idaho Falls in eastern Idaho, Ralph Stanton, 51, expressed his outrage. According to this well-built former worker at the Idaho National Laboratory, he was told that his radiation exposure was not serious despite suffering plutonium contamination. He added, “Who will take responsibility if I get ill in 10 years?”

The Idaho National Laboratory has played an important role in U.S. nuclear research. The laboratory is administered by the DOE, but its operation was outsourced to a private business called BEA. Mr. Stanton and 15 other workers were involved in a plutonium contamination accident in November 2011 at a facility called ZPPR, which was used for fast reactor tests between the 1960s and 1992.

There was still a large amount of fuel called “clamshell” at the facility. The fuel was in metal containers that looked like two plates put together. The accident occurred when workers were taking out plutonium from those containers and putting it into others.

According to Mr. Stanton, those containers were at least 30 years old, and some of them were hot. Workers did not use glove boxes (airtight containers) but worktables similar to those used for salad bars at family restaurants. Efficiency was given the highest priority, he added.

His anxiety became a reality. One of the clamshells was made of plastic and it was wrapped with tape. He told the person in charge that something was clearly wrong. But the person did not take him seriously and ordered him to continue his work. He had no choice but to open the container. A worker next to him shouted, “Powder!” The plutonium was oxidized when it became exposed to the air and turned into pepper-like powder.

The alarm for the worktable was out of order, and there was a gap of time before another alarm several meters away went off. After fleeing, Mr. Stanton was told to take off his clothes but he was not allowed to shower there because the tank for contaminated water was said to be full. An industrial doctor detected americium 241, a radioactive substance, in Mr. Stanton’s lungs, which is considered evidence of the presence of plutonium. That night he vomited numerous times at home. But the next day, his boss flatly stated that his symptoms were caused by the flu.

His family was also affected by this problem. The Stantons had an expert examine his house on their own, and a small amount of plutonium was detected. As they could not afford to move to a new house, they had to clean up their house wearing gas masks. As they recalled this experience, Mr. Stanton’s wife Jodi, 47, sat beside him and wiped away tears.

In its investigative report on the accident, the DOE determined that security measures had been lacking and leveled a fine against BEA. Later, measures to prevent a recurrence were implemented.

But Mr. Stanton had nowhere to vent his anger. The company said that his exposure dose was 100 millirems (1 millisievert), a figure that he found not believable. If that was the case, the prospect of receiving compensation for the accident was dim. He demanded that the company disclose more information and maintained that his house had been contaminated, too, which resulted in a fierce clash with the company. He was fired with the contention that he had dozed off during work at the end of 2013. He then took legal action against BEA, claiming that what the company did was illegal and a reprisal against a whistle-blower.

Tami Thatcher is a former safety analyst at the DOE and now belongs to the Environmental Defense Institute, a civil organization that is supporting Mr. Stanton’s effort. She said that his case was a result of extremely sloppy management, but that in many cases the companies try to make such accidents look less serious.

While Mr. Stanton wrestles with anxiety over his health, he also acknowledged that work involving nuclear materials cannot be performed without the possibility of exposure to radiation.

Major newspaper group reports full picture of health damage

At the Idaho National Laboratory, three soldiers died when a core meltdown accident occurred at an Army test reactor in 1961. A local environmental organization points out that there is a large amount of radioactive waste at this site and that the soil and groundwater are contaminated.

Radioactive contamination is a nationwide problem. The Hanford Site in the state of Washington, where the plutonium for the Nagasaki bomb was produced, is dubbed the most polluted nuclear facility in the United States.

How many workers at nuclear facilities in this nation have been suffering from health problems? Surprisingly, the whole scope of this problem was not fully understood until recently. Even when workers are confident that they developed cancer or other diseases as a result of radiation exposure, there are difficult obstacles to overcome before they can sue the DOE or other parties, and many of them bear their suffering in silence.

A change was brought about in 2000. The Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act (EEOICPA) was established by Congress, enabling workers to seek compensation without a trial.

This caught the attention of the McClatchy Company, a major newspaper group. When the company requested the disclosure of related information, the U.S. government released 70 million items of electronic data on compensation applications. They analyzed the data, interviewed people linked to this issue, and reported the results through its 29 local newspapers. The company’s website provides an enormous amount of information on more than 100,000 people, including their diseases and whether they are still living or not.

At his office in Washington D.C., reporter Rob Hotakainen, said, “At least 33,488 people who were recognized as victims have died.” He added that the suffering of each person must be understood, not just the number of victims, and that the health damage has not ended even though security measures have been stepped up since the Cold War era.

The government had expected to spend 120 million dollars (12.4 billion yen) to compensate 3,000 people annually. But, in reality, 12 billion dollars (1.248 trillion yen) was spent in 14 years, which is seven times larger than estimated. Still, fewer than half the applicants can obtain compensation because it is difficult to prove that they suffered radiation exposure, depending on the exposure dose or on the facility where they worked.

The newspaper company questions the government’s attitude, saying, “The U.S. is planning to modernize its nuclear arsenal, spending one trillion dollars (104 trillion yen) in the future. Is the country learning any lessons from the suffering of these people?”

Energy Employees Occupational Illness Compensation Program Act established based on epidemiological surveys

The EEOICPA was established after the administration of then President Bill Clinton fully conceded that workers at U.S. nuclear-related facilities were suffering damage to their health. Congress also made clear that radioactive materials are extremely dangerous and even exposure to low doses of radiation can be medically harmful.

In addition to the complaints made by the victims, the results of many epidemiological surveys were respected. But survey results are not always consistent.

According to one research study conducted at Oak Ridge, Tennessee, where the uranium used for the Hiroshima bomb was produced, the excess relative risk of dying from all types of cancer is 10 times that of A-bomb survivors, and the accumulation of exposure doses from the age of 45 and up can increase mortality risks. There is a counterargument that cancer deaths are mostly influenced by smoking. One study says that cancer cases increased even for those whose doses were within the safety standards, while another study shows a contrary result.

David Richardson, an associate professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, carried out an epidemiological survey at Oak Ridge. Dr. Richardson said we must be aware that, unlike nuclear power plants, workers at a facility where various materials are handled are suffering a complex form of contamination from both nuclear and other harmful substances.

Keywords

Idaho National Laboratory

The Idaho National Laboratory’s predecessor was opened in 1949. The laboratory has had 52 nuclear reactors on a site that is larger than Tokyo. Research is pursued on the nuclear fuel cycle, advanced nuclear reactors, nuclear non-proliferation technologies, and countermeasures against cyberattacks. The laboratory’s history is closely tied to military affairs. The nuclear reactor for nuclear-powered vessels was first developed at this laboratory. Spent fuel was reprocessed at this laboratory and was used to produce nuclear weapons at different facilities.

(Originally published on June 20, 2016)