Gray area: Effects of exposure to low-level radiation, Part 7 [1]

Nov. 3, 2016

Path to the future for sufferers of the Fukushima nuclear accident

by Yumi Kanazaki and Yota Baba, Staff Writers

In making use of nuclear energy, human beings have opened a Pandora’s box. This series concludes with Part 7, which attempts to chart a path to the future.

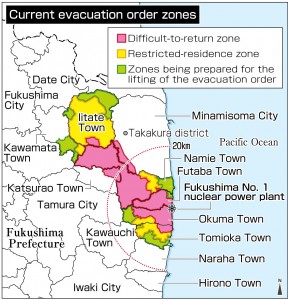

After the nuclear accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), government-designated evacuation zones covered areas within 20 kilometers of the nuclear plant as well as those outside a 20-kilometer radius but over which drifted plumes that were thick with radioactive substances. In the belief that airborne radiation levels have decreased over the passage of time and as a result of decontamination work, the government is now lifting its evacuation orders and urging residents who evacuated to areas both inside and outside Fukushima Prefecture to return to their homes. The guideline used by the government to make this decision is based on the annual radiation level measuring 20 mSv or lower. There are, however, a large number of residents who remain very concerned about the impact of the government-set radiation levels on their health.

Resisting the government’s return policy for local residents

The city of Minamisoma in Fukushima Prefecture has a population of around 70,000 and is located to the north of the Fukushima nuclear power plant. After the nuclear accident, various evacuation orders were issued to the city, eventually dividing the city into as many as five different zones at times, ranging from a difficult-to-return zone, into which entry is prohibited in principle, to a zone where no evacuation order was ever given. As a result of the recent lifting of the evacuation order, only the difficult-to-return zones remain.

“Government officials state that, on the basis of the radiation levels measured one meter above the ground, current radiation levels do not pose a threat to human health. But do they cut the grass without inhaling?” wondered Shinobu Shimakage, 75, expressing distrust. Prior to being interviewed by the Chugoku Shimbun, Mr. Shimakage had donned a mask to cut the grass in front of his house, which is located in the mountainous Takakura district in the western part of Minamisoma. He currently lives in a temporary housing unit with his wife in a part of the city that contains low levels of radiation, and often visits his home during the day to maintain the property.

Mr. Shimakage’s house is located in a zone where evacuation orders were not issued, but the area does contain localized spots of high levels of radiation. As a result, his house was designated as a specific spot where evacuation is recommended. But as this designation was set for individual homes as a “spot,” his land on the opposite side of the river behind his house was designated a restricted-residence zone. The line dividing the two zones was drawn on the river with a width of only a few meters.

In December 2014, the nation’s local nuclear emergency response headquarters lifted the designation of “specific spots recommended for evacuations” in areas where annual radiation levels had dropped to less than 20 mSv. In response to the government’s decision, the Tokyo Electric Power Company ended emotional distress compensation payments of 100,000 yen per month for households located at specific spots recommended for evacuation. For the restricted-residence zone where Mr. Shimakage’s land is located, the evacuation order was lifted this past July.

All evacuation orders will be lifted by the end of March 2017 in the other remaining evacuation zones in Fukushima Prefecture, except for the difficult-to-return zones. The housing assistance for voluntary evacuees will also, in principle, be discontinued in stages.

“In other parts of Japan, the radiation protection guideline is set at 1 mSv or less. Why doesn’t that level apply to Fukushima?” Mr. Shimakage said, voicing his anger. He pointed to a water tank at the side of his house where he had been breeding forest green treefrogs, as a hobby, for 40 years. “There was a sudden increase in the number of tadpoles that had lost their color and had missing legs,” he said. “Many of them died before developing into frogs. Such things, which had never been seen before the Fukushima accident, were widely seen in 2013. This is the truth.”

Mr. Shimakage also feels frustrated when it comes to products produced in nearby mountains. In Japan, the allowable limit for radioactive substances contained in food products is set at 100 becquerels per kilogram. By comparison, last year, the radiation level of angelica tree buds was a maximum of 1,400 becquerels per kilogram, and subsequently increased to 1,900 becquerels per kilogram this year. “Although we have to test for radiation levels in all products, we have no choice but to discard them if their radiation levels exceed the allowable limits that have been set.” Mr. Shimakage said that some angelica tree buds on a tree standing just one meter away, for example, contain significantly lower levels of radiation and he finds it very frustrating that the radiation levels cannot be known before undertaking these measurements.

“There’s no sense in measuring airborne radiation levels only, especially radiation levels at the entrance to a house that has undergone decontamination work. Radioactive contamination is not really uniform. Unlike Jizo Kannon Bodhisattva, human beings wander about and sometimes sit down on rocks,” said Yoichi Ozawa, 60, a friend of Mr. Shimakage, as he began measuring radiation contamination levels on the surface of some garden rocks at Mr. Shimakage’s house.

“If converted into units of becquerels per square centimeter, the radiation levels in this area are seven times four becquerels, the guideline level used for designating a radiation control area. According to the government’s policy, it seems that the government is forcing us to live in an area labeled with a radiation mark. Therefore, it’s only natural that some households, especially those with children, aren’t willing to return to their homes,” Mr. Ozawa said. When he measured the radiation levels on the surface of rocks next to the rock measured previously, he found that the levels had dropped dramatically, clearly underscoring the point that the levels are “not uniform.”

As the secretariat of plaintiffs, Mr. Ozawa has filed a lawsuit, which he refers to as the “20 mSv withdraw suit,” at the Tokyo District Court. In this lawsuit, in which he represents a total of 206 households, including Mr. Shimakage, he demands that the government withdraw the lifting of the designation of specific spots recommended for evacuation. The households, which are located next to houses for which evacuation has been recommended but are not designated as a specific spot for evacuation, have joined the plaintiffs in order to expand the government’s specific evacuation recommendation zone.

It is not easy to resist the government’s indiscriminate order urging all the evacuees to return to their homes. However, when asked as to why Mr. Shimakage, Mr. Ozawa, and other plaintiffs are taking action against the government, they answered that they have a responsibility for the generations that will follow. They are saying, in effect, “The government has underestimated the true circumstances of the radiation contamination, so we have to protest this and seek a judgment from the court. If we don’t pursue the matter, generations to come could be harmed by diseases caused by radiation.” The plaintiffs have been collecting soil samples at all possible locations and accumulating data on their measurements.

Interview with Tadashi Hongyo, professor of radiation biology at Osaka University

The rationale behind the government’s decision to lift the evacuation orders is based on its judgment that the risk of developing diseases from exposure to radiation doses of 100 mSv or less is as low as the health risks from smoking and other factors. But is something being overlooked? The Chugoku Shimbun spoke with Tadashi Hongyo, a professor of radiation biology at the Graduate School of Medicine of Osaka University who studies internal exposure to low levels of radiation.

What are your thoughts about the annual value of 20 mSv?

Sensitivity to radiation differs greatly from person to person. As no one can determine exactly who is susceptible to radiation and who is not, it is better to avoid any exposure to radiation to the extent possible. In the areas ravaged by the Chernobyl nuclear accident, people have been forced to move out of areas where the annual radiation levels are 5 mSv or higher. This system is safer compared to the return policy for local residents being pursued by the Japanese government. When viewing such conditions and making decisions, it is important to always prioritize those who are weak and vulnerable.

Could you talk more about how sensitivity to radiation varies from person to person?

A small percentage of people are believed to have genes which make them more susceptible to radiation, and that susceptibility is not uniform. This is similar to the sensitivity to alcohol where some people feel sick just from smelling it; some people can drink only one glass of alcohol; and some people can drink a lot. Sensitivity to radiation can also differ significantly depending on the person’s age and physical constitution.

“Biological half-life,” the time it takes for the radioactivity inside the body to fall to half of its original value as a result of metabolism and excretion, varies some 100 times between individuals. In tests using mice to measure the dose of internal exposure, there were large differences between the mice depending on the condition of their stomach and what was inside their stomach at the time of their exposure to radiation.

How were these experiments using mice carried out?

The mice were administered radioactive iodine under a wide variety of conditions and we observed how the iodine was taken into their thyroid glands. The mice that were given milk before being administered iodine took in more radioactive iodine. To the contrary, in the mice that were given stable iodine tablets before being administered iodine, the take-in level of iodine was reduced by some 90 percent. Kelp and iodine mouth wash which was diluted to 30 times were confirmed to have an effect equivalent to that of stable iodine tablets.

The results of your experiments can be used if another nuclear accident occurs.

It goes without saying that another nuclear accident must never again take place. If a nuclear accident occurs, however, it is absolutely essential that we are prepared to avoid repeating the same mistakes that were made five and a half years ago in Fukushima.

So, if a nuclear disaster occurs, it would be vital to measure the amount of radiation exposure to the thyroid glands and provide stable iodine tablets for those exposed to radiation exceeding a certain level. There would be no time to lose. However, based on current government policy, it is likely that there would be a lack of stable iodine tablets available at the time of the next nuclear accident. Furthermore, the government’s evacuation drills which were established after the Fukushima nuclear accident do not include any examinations of the victims’ thyroid glands. I’m very suspicious of how seriously the government has taken the lessons they should have learned from past experience.

It is said that the current annual radiation levels in Fukushima are just a few millisieverts at most and that the dose of internal radiation is minute based on measurements using a whole body counter.

This does not mean that people have not experienced internal radiation exposure. It is in fact very difficult to measure the amount of radioactive substances that have been deposited in individual organs and tissues. Sievert values are not actual measurements, rather they are a value obtained by multiplying a set coefficient by a value expressed in becquerel units. In addition, the sievert value does not reflect differences in the chemical properties such as cesium and strontium.

Furthermore, the whole body counter can measure only gamma rays, and cannot detect any strontium which emits beta rays.

The radiation protection standard used by the government for making decisions regarding lifting evacuation orders is based on A-bomb survivors’ data prepared by the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (in Minami Ward, Hiroshima).

Research on the A-bomb survivors has not taken into consideration the influence of internal exposure to radiation. The people who were susceptible to radiation and those who died within five years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima were not subject to the investigation. So the investigation results of A-bomb survivors and victims do not apply to the people of Fukushima in many respects. It would therefore be better to try to learn more from the data and experiences involving the Chernobyl nuclear accident.

With regard to the effects of exposure to low levels of radiation, it is said that harm to human health resulting from smoking is much greater than harm resulting from low-level radiation exposure, and thus it is difficult to understand the risk to human health from low-level radiation exposure.

The risk of cancer resulting from exposure to low levels of radiation is difficult to ascertain as a statistical value because many people have other risk factors as well, such as smoking for example. But this does not mean that exposure to low levels of radiation is safe or does not harm human health, and it should not be understood in that way. Both smoking and low-level radiation exposure ought to be avoided at all costs.

Keywords

Significance of 20 millisieverts

The rough guideline “20 millisieverts or lower annually,” which the government uses for lifting the evacuation orders, is based on the reference levels that the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), comprised of radiation and epidemiology experts, has released in the form of recommendations. The organization seeks to limit the annual radiation exposure dose for the general public (citizens) to 1 mSv in the long run. However, in the case of emergency situations, such as a nuclear accident, the ICRP indicates that the acceptable exposure limit can be increased to 20 to 100 mSv and, during periods of post-accident reconstruction work, the limit should be maintained at no more than 20 mSv. The ICRP’s long-term aim is to achieve radiation exposure of no more than 1 mSv. Based on the ICRP recommendations, ICRP member countries, including Japan, set their own protection standards for radiation exposure for nuclear power plant workers, medical staff, and the general public.

(Originally published on November 3, 2016)

by Yumi Kanazaki and Yota Baba, Staff Writers

In making use of nuclear energy, human beings have opened a Pandora’s box. This series concludes with Part 7, which attempts to chart a path to the future.

After the nuclear accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO), government-designated evacuation zones covered areas within 20 kilometers of the nuclear plant as well as those outside a 20-kilometer radius but over which drifted plumes that were thick with radioactive substances. In the belief that airborne radiation levels have decreased over the passage of time and as a result of decontamination work, the government is now lifting its evacuation orders and urging residents who evacuated to areas both inside and outside Fukushima Prefecture to return to their homes. The guideline used by the government to make this decision is based on the annual radiation level measuring 20 mSv or lower. There are, however, a large number of residents who remain very concerned about the impact of the government-set radiation levels on their health.

Resisting the government’s return policy for local residents

The city of Minamisoma in Fukushima Prefecture has a population of around 70,000 and is located to the north of the Fukushima nuclear power plant. After the nuclear accident, various evacuation orders were issued to the city, eventually dividing the city into as many as five different zones at times, ranging from a difficult-to-return zone, into which entry is prohibited in principle, to a zone where no evacuation order was ever given. As a result of the recent lifting of the evacuation order, only the difficult-to-return zones remain.

“Government officials state that, on the basis of the radiation levels measured one meter above the ground, current radiation levels do not pose a threat to human health. But do they cut the grass without inhaling?” wondered Shinobu Shimakage, 75, expressing distrust. Prior to being interviewed by the Chugoku Shimbun, Mr. Shimakage had donned a mask to cut the grass in front of his house, which is located in the mountainous Takakura district in the western part of Minamisoma. He currently lives in a temporary housing unit with his wife in a part of the city that contains low levels of radiation, and often visits his home during the day to maintain the property.

Mr. Shimakage’s house is located in a zone where evacuation orders were not issued, but the area does contain localized spots of high levels of radiation. As a result, his house was designated as a specific spot where evacuation is recommended. But as this designation was set for individual homes as a “spot,” his land on the opposite side of the river behind his house was designated a restricted-residence zone. The line dividing the two zones was drawn on the river with a width of only a few meters.

In December 2014, the nation’s local nuclear emergency response headquarters lifted the designation of “specific spots recommended for evacuations” in areas where annual radiation levels had dropped to less than 20 mSv. In response to the government’s decision, the Tokyo Electric Power Company ended emotional distress compensation payments of 100,000 yen per month for households located at specific spots recommended for evacuation. For the restricted-residence zone where Mr. Shimakage’s land is located, the evacuation order was lifted this past July.

All evacuation orders will be lifted by the end of March 2017 in the other remaining evacuation zones in Fukushima Prefecture, except for the difficult-to-return zones. The housing assistance for voluntary evacuees will also, in principle, be discontinued in stages.

“In other parts of Japan, the radiation protection guideline is set at 1 mSv or less. Why doesn’t that level apply to Fukushima?” Mr. Shimakage said, voicing his anger. He pointed to a water tank at the side of his house where he had been breeding forest green treefrogs, as a hobby, for 40 years. “There was a sudden increase in the number of tadpoles that had lost their color and had missing legs,” he said. “Many of them died before developing into frogs. Such things, which had never been seen before the Fukushima accident, were widely seen in 2013. This is the truth.”

Mr. Shimakage also feels frustrated when it comes to products produced in nearby mountains. In Japan, the allowable limit for radioactive substances contained in food products is set at 100 becquerels per kilogram. By comparison, last year, the radiation level of angelica tree buds was a maximum of 1,400 becquerels per kilogram, and subsequently increased to 1,900 becquerels per kilogram this year. “Although we have to test for radiation levels in all products, we have no choice but to discard them if their radiation levels exceed the allowable limits that have been set.” Mr. Shimakage said that some angelica tree buds on a tree standing just one meter away, for example, contain significantly lower levels of radiation and he finds it very frustrating that the radiation levels cannot be known before undertaking these measurements.

“There’s no sense in measuring airborne radiation levels only, especially radiation levels at the entrance to a house that has undergone decontamination work. Radioactive contamination is not really uniform. Unlike Jizo Kannon Bodhisattva, human beings wander about and sometimes sit down on rocks,” said Yoichi Ozawa, 60, a friend of Mr. Shimakage, as he began measuring radiation contamination levels on the surface of some garden rocks at Mr. Shimakage’s house.

“If converted into units of becquerels per square centimeter, the radiation levels in this area are seven times four becquerels, the guideline level used for designating a radiation control area. According to the government’s policy, it seems that the government is forcing us to live in an area labeled with a radiation mark. Therefore, it’s only natural that some households, especially those with children, aren’t willing to return to their homes,” Mr. Ozawa said. When he measured the radiation levels on the surface of rocks next to the rock measured previously, he found that the levels had dropped dramatically, clearly underscoring the point that the levels are “not uniform.”

As the secretariat of plaintiffs, Mr. Ozawa has filed a lawsuit, which he refers to as the “20 mSv withdraw suit,” at the Tokyo District Court. In this lawsuit, in which he represents a total of 206 households, including Mr. Shimakage, he demands that the government withdraw the lifting of the designation of specific spots recommended for evacuation. The households, which are located next to houses for which evacuation has been recommended but are not designated as a specific spot for evacuation, have joined the plaintiffs in order to expand the government’s specific evacuation recommendation zone.

It is not easy to resist the government’s indiscriminate order urging all the evacuees to return to their homes. However, when asked as to why Mr. Shimakage, Mr. Ozawa, and other plaintiffs are taking action against the government, they answered that they have a responsibility for the generations that will follow. They are saying, in effect, “The government has underestimated the true circumstances of the radiation contamination, so we have to protest this and seek a judgment from the court. If we don’t pursue the matter, generations to come could be harmed by diseases caused by radiation.” The plaintiffs have been collecting soil samples at all possible locations and accumulating data on their measurements.

Interview with Tadashi Hongyo, professor of radiation biology at Osaka University

The rationale behind the government’s decision to lift the evacuation orders is based on its judgment that the risk of developing diseases from exposure to radiation doses of 100 mSv or less is as low as the health risks from smoking and other factors. But is something being overlooked? The Chugoku Shimbun spoke with Tadashi Hongyo, a professor of radiation biology at the Graduate School of Medicine of Osaka University who studies internal exposure to low levels of radiation.

What are your thoughts about the annual value of 20 mSv?

Sensitivity to radiation differs greatly from person to person. As no one can determine exactly who is susceptible to radiation and who is not, it is better to avoid any exposure to radiation to the extent possible. In the areas ravaged by the Chernobyl nuclear accident, people have been forced to move out of areas where the annual radiation levels are 5 mSv or higher. This system is safer compared to the return policy for local residents being pursued by the Japanese government. When viewing such conditions and making decisions, it is important to always prioritize those who are weak and vulnerable.

Could you talk more about how sensitivity to radiation varies from person to person?

A small percentage of people are believed to have genes which make them more susceptible to radiation, and that susceptibility is not uniform. This is similar to the sensitivity to alcohol where some people feel sick just from smelling it; some people can drink only one glass of alcohol; and some people can drink a lot. Sensitivity to radiation can also differ significantly depending on the person’s age and physical constitution.

“Biological half-life,” the time it takes for the radioactivity inside the body to fall to half of its original value as a result of metabolism and excretion, varies some 100 times between individuals. In tests using mice to measure the dose of internal exposure, there were large differences between the mice depending on the condition of their stomach and what was inside their stomach at the time of their exposure to radiation.

How were these experiments using mice carried out?

The mice were administered radioactive iodine under a wide variety of conditions and we observed how the iodine was taken into their thyroid glands. The mice that were given milk before being administered iodine took in more radioactive iodine. To the contrary, in the mice that were given stable iodine tablets before being administered iodine, the take-in level of iodine was reduced by some 90 percent. Kelp and iodine mouth wash which was diluted to 30 times were confirmed to have an effect equivalent to that of stable iodine tablets.

The results of your experiments can be used if another nuclear accident occurs.

It goes without saying that another nuclear accident must never again take place. If a nuclear accident occurs, however, it is absolutely essential that we are prepared to avoid repeating the same mistakes that were made five and a half years ago in Fukushima.

So, if a nuclear disaster occurs, it would be vital to measure the amount of radiation exposure to the thyroid glands and provide stable iodine tablets for those exposed to radiation exceeding a certain level. There would be no time to lose. However, based on current government policy, it is likely that there would be a lack of stable iodine tablets available at the time of the next nuclear accident. Furthermore, the government’s evacuation drills which were established after the Fukushima nuclear accident do not include any examinations of the victims’ thyroid glands. I’m very suspicious of how seriously the government has taken the lessons they should have learned from past experience.

It is said that the current annual radiation levels in Fukushima are just a few millisieverts at most and that the dose of internal radiation is minute based on measurements using a whole body counter.

This does not mean that people have not experienced internal radiation exposure. It is in fact very difficult to measure the amount of radioactive substances that have been deposited in individual organs and tissues. Sievert values are not actual measurements, rather they are a value obtained by multiplying a set coefficient by a value expressed in becquerel units. In addition, the sievert value does not reflect differences in the chemical properties such as cesium and strontium.

Furthermore, the whole body counter can measure only gamma rays, and cannot detect any strontium which emits beta rays.

The radiation protection standard used by the government for making decisions regarding lifting evacuation orders is based on A-bomb survivors’ data prepared by the Radiation Effects Research Foundation (in Minami Ward, Hiroshima).

Research on the A-bomb survivors has not taken into consideration the influence of internal exposure to radiation. The people who were susceptible to radiation and those who died within five years after the atomic bombing of Hiroshima were not subject to the investigation. So the investigation results of A-bomb survivors and victims do not apply to the people of Fukushima in many respects. It would therefore be better to try to learn more from the data and experiences involving the Chernobyl nuclear accident.

With regard to the effects of exposure to low levels of radiation, it is said that harm to human health resulting from smoking is much greater than harm resulting from low-level radiation exposure, and thus it is difficult to understand the risk to human health from low-level radiation exposure.

The risk of cancer resulting from exposure to low levels of radiation is difficult to ascertain as a statistical value because many people have other risk factors as well, such as smoking for example. But this does not mean that exposure to low levels of radiation is safe or does not harm human health, and it should not be understood in that way. Both smoking and low-level radiation exposure ought to be avoided at all costs.

Keywords

Significance of 20 millisieverts

The rough guideline “20 millisieverts or lower annually,” which the government uses for lifting the evacuation orders, is based on the reference levels that the International Commission on Radiological Protection (ICRP), comprised of radiation and epidemiology experts, has released in the form of recommendations. The organization seeks to limit the annual radiation exposure dose for the general public (citizens) to 1 mSv in the long run. However, in the case of emergency situations, such as a nuclear accident, the ICRP indicates that the acceptable exposure limit can be increased to 20 to 100 mSv and, during periods of post-accident reconstruction work, the limit should be maintained at no more than 20 mSv. The ICRP’s long-term aim is to achieve radiation exposure of no more than 1 mSv. Based on the ICRP recommendations, ICRP member countries, including Japan, set their own protection standards for radiation exposure for nuclear power plant workers, medical staff, and the general public.

(Originally published on November 3, 2016)