Gray area: Effects of exposure to low-level radiation, Part 4 [1]

Jun. 19, 2016

In a nuclear superpower: People living in downwind area have difficulty proving damage

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Seventy-one years ago, the United States opened the nuclear era by detonating atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the first nuclear attacks in human history. During the Cold War, the United States and the former Soviet Union were engaged in a nuclear arms race. The harder they worked to advance their nuclear technology for both military and civilian uses, the more hibakusha (nuclear sufferers) were created. These hibakusha are different from those of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, who were exposed to a large amount of radiation instantaneously at close range. Sufferers in the United States have difficulty proving that their health has been harmed due to radiation exposure, leaving some stranded without relief measures. In this article, the Chugoku Shimbun explores the issue of low-level radiation exposure in the nuclear superpower and assesses the challenges it faces.

Difficult to prove damage in downwind area

Fields of potatoes stretch as far as the eye can see in the western U.S. state of Idaho. Some 50 kilometers to the northwest of the capital Boise, a peaceful town lies in a basin. This is Emmett, home to 6,600 people. The town developed as a way-stop in the 1860s for people heading west to join the Gold Rush.

Tona Henderson, 55, runs a doughnut shop in Emmett. She represents Idaho Downwinders, a group of residents who claim that they have suffered health damage as a result of nuclear testing. She paused from making doughnuts and said, “We want to be recognized as downwinders. How much longer do we have to wait?”

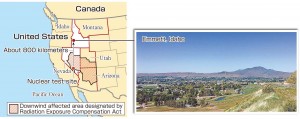

The downwind area is where wind carried radioactive fallout from the nuclear tests. But Emmett sits 800 kilometers from the Nevada Test Site, the same distance between Hiroshima and southern Fukushima Prefecture. The fact that radioactive fallout could travel such a long distance is surprising.

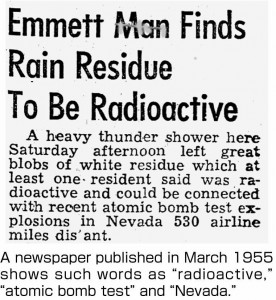

Ms. Henderson showed a copy of a newspaper article published in March 1955. It says that white residue was detected in Emmett after a heavy rain. According to the article, a dosimeter reading was twice as high as ordinarily would be found. But it added that this circumstance would not affect human health. Ms. Henderson said that she discovered the article only recently.

Her perceptions of nuclear testing changed 12 years ago when she learned that the National Cancer Institute issued a report in 1997 about atmospheric nuclear tests conducted in the 1950s.

Based on a variety of past data on radioactive fallout and meteorological conditions, among other things, at the time, the report used a calculation model and estimated the radiation exposure level for a person’s thyroid in each of the 3,000 counties across the nation. Depending on these conditions, people could have received doses of up to 16 rads (160 mGy) in some counties. The report said some counties in Idaho and Montana, including Gem County, in which Emmett is located, were estimated to have the highest doses in the country.

Ms. Henderson was particularly troubled to learn that children who were between three months to five years of age when the nuclear tests were conducted may have been exposed to 10 times as much radiation as adults, because children drink a lot more milk. Her family lived on a farm and led a self-sufficient way of life. She suspected that her thyroid condition was caused by nuclear testing. Her mother cried, saying that she gave her children freshly drawn milk because she thought it was good for them.

Her father and uncle also had thyroid problems. Her mother got breast cancer and her brother developed three cancers. She thought something was wrong. Suspecting that other people may have had similar health issues, she urged local residents to attend a gathering, which attracted 300 people. She then decided to take action.

The United States has the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) for people suffering health problems resulting from that nation’s nuclear testing. Residents of the designated area, which extends over the states of Nevada, Arizona, and Utah, can apply for compensation money if certain conditions are met. Idaho Downwinders are approaching members of Congress elected from the state and calling for the designated area to be expanded.

But they have not yet been successful in wielding influence over Congress, and a revision to the law is nowhere in sight. They are feeling growing frustration, wondering whether the government and politicians are waiting for these nuclear sufferers to die.

In Ms. Henderson’s shop are photos of about 800 people in military uniforms. Her regular customers have brought photos of themselves when they were young or of family members who are now deceased.

She said, “I’m a patriot. But I praise those who worked for the country and those who sacrificed themselves for national policies, not the government.” She will continue to fight for compensation for the downwinders.

Steven Simon, head of the Dosimetry Unit at the Radiation Epidemiology Branch of the National Cancer Institute: Winds disperse radioactive particles

To obtain more information on nuclear fallout in the United States, the Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Steven Simon, head of the Dosimetry Unit at the Radiation Epidemiology Branch of the National Cancer Institute. He has written reports on nuclear tests conducted at the test site in Nevada and been involved in research projects on exposure doses in the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean and Semipalatinsk in the former Soviet Union.

It’s surprising that nuclear fallout spread over such a wide range as 100 nuclear tests were being conducted in the atmosphere in Nevada.

This is because a huge amount of highly radioactive dust was blown into the air when a fireball touched the ground in an experiment where a bomb exploded near the ground. In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the explosions were 600 meters above the ground, and there wasn’t much fallout. This is part of the difference.

Large particles such as dirt fell relatively near the hypocenter, but little particles were blown by the wind and fell back onto the ground when it rained, and hot spots were made.

The NCI report refers to the way people drink milk. Does a daily habit like this have a significant impact on people’s internal exposure to radiation?

The thyroid is susceptible to the effect of radiation. When cows eat a lot of grass that is laced with fallout, radioactive iodine, which is water-soluble, is concentrated in the milk. The half-life of iodine-131 is eight days. Among those who lived in the same area, or among people who were children when nuclear tests were being conducted in the 1950s, the more fresh milk they drank, the more radioactive iodine was taken into their thyroids.

You also give risk assessments for thyroid cancer in this respect.

In the absence of any fallout exposure, about 400,000 people would develop thyroid cancer in their lifetimes. We added about 49,000 because of fallout.

That’s a lot.

It’s natural for people to worry, but let me stress that there is great uncertainty when it comes to statistics. In this day and age, 40 percent of the population die from cancer. There are many causes of cancer and there is no telling what the cause is in each case. It is like trying to hear what I say in a low voice in a noisy place. You can’t hear me because there’s too much noise in the background. And this wasn’t exposure to high doses of radiation and it happened decades ago. The exact cause can’t be known.

Is radioactive iodine the only problem?

Fallout from nuclear tests conducted by the former Soviet Union fell onto the ground after floating in the stratosphere for about one year. Even though it’s a smaller amount than in Nevada, radioactive cesium has been found in the eastern part of the United States. Fallout has spread around the world.

The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act: 18,550 victims identified, lump sums provided

The United States conducted 210 nuclear tests in the atmosphere before it signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) in 1963. About 100 of them were carried out at a nuclear test site in Nevada. Responding to complaints from people living in the vicinity and soldiers involved in the testing that the tests did harm to their health, the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) was enacted in 1990.

RECA covers people who lived in the downwind affected area, who were engaged in nuclear tests, and who worked in uranium mines or in the process of refining it. If an individual who lived in the downwind area comes down with a designated disease, including breast cancer, that person can receive a lump sum of 50,000 dollars (5.2 million yen) if his or her application is accepted. According to the Department of Justice, 18,550 out of 23,233 compensation applications from those living in the affected area were accepted by February 2015.

But there are many conditions which conflict with the reality of nuclear tests. Only parts of Nevada, Arizona, and Utah have been designated as a downwind affected area, and Idaho is not included.

Some politicians are making bipartisan efforts with a view to revising the law. Lindsay Nothern, a secretary to Michael Crapo, a Republican senator from Idaho, is in charge of this issue at a Boise office. Mr. Nothern stressed that there is a lack of understanding that this is a nationwide problem. He added that politicians from the eastern part of the country have little interest in this issue and that efforts are being made to bring better understanding to all lawmakers.

(Originally published on June 19, 2016)

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Seventy-one years ago, the United States opened the nuclear era by detonating atomic bombs over Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the first nuclear attacks in human history. During the Cold War, the United States and the former Soviet Union were engaged in a nuclear arms race. The harder they worked to advance their nuclear technology for both military and civilian uses, the more hibakusha (nuclear sufferers) were created. These hibakusha are different from those of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, who were exposed to a large amount of radiation instantaneously at close range. Sufferers in the United States have difficulty proving that their health has been harmed due to radiation exposure, leaving some stranded without relief measures. In this article, the Chugoku Shimbun explores the issue of low-level radiation exposure in the nuclear superpower and assesses the challenges it faces.

Difficult to prove damage in downwind area

Fields of potatoes stretch as far as the eye can see in the western U.S. state of Idaho. Some 50 kilometers to the northwest of the capital Boise, a peaceful town lies in a basin. This is Emmett, home to 6,600 people. The town developed as a way-stop in the 1860s for people heading west to join the Gold Rush.

Tona Henderson, 55, runs a doughnut shop in Emmett. She represents Idaho Downwinders, a group of residents who claim that they have suffered health damage as a result of nuclear testing. She paused from making doughnuts and said, “We want to be recognized as downwinders. How much longer do we have to wait?”

The downwind area is where wind carried radioactive fallout from the nuclear tests. But Emmett sits 800 kilometers from the Nevada Test Site, the same distance between Hiroshima and southern Fukushima Prefecture. The fact that radioactive fallout could travel such a long distance is surprising.

Ms. Henderson showed a copy of a newspaper article published in March 1955. It says that white residue was detected in Emmett after a heavy rain. According to the article, a dosimeter reading was twice as high as ordinarily would be found. But it added that this circumstance would not affect human health. Ms. Henderson said that she discovered the article only recently.

Her perceptions of nuclear testing changed 12 years ago when she learned that the National Cancer Institute issued a report in 1997 about atmospheric nuclear tests conducted in the 1950s.

Based on a variety of past data on radioactive fallout and meteorological conditions, among other things, at the time, the report used a calculation model and estimated the radiation exposure level for a person’s thyroid in each of the 3,000 counties across the nation. Depending on these conditions, people could have received doses of up to 16 rads (160 mGy) in some counties. The report said some counties in Idaho and Montana, including Gem County, in which Emmett is located, were estimated to have the highest doses in the country.

Ms. Henderson was particularly troubled to learn that children who were between three months to five years of age when the nuclear tests were conducted may have been exposed to 10 times as much radiation as adults, because children drink a lot more milk. Her family lived on a farm and led a self-sufficient way of life. She suspected that her thyroid condition was caused by nuclear testing. Her mother cried, saying that she gave her children freshly drawn milk because she thought it was good for them.

Her father and uncle also had thyroid problems. Her mother got breast cancer and her brother developed three cancers. She thought something was wrong. Suspecting that other people may have had similar health issues, she urged local residents to attend a gathering, which attracted 300 people. She then decided to take action.

The United States has the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) for people suffering health problems resulting from that nation’s nuclear testing. Residents of the designated area, which extends over the states of Nevada, Arizona, and Utah, can apply for compensation money if certain conditions are met. Idaho Downwinders are approaching members of Congress elected from the state and calling for the designated area to be expanded.

But they have not yet been successful in wielding influence over Congress, and a revision to the law is nowhere in sight. They are feeling growing frustration, wondering whether the government and politicians are waiting for these nuclear sufferers to die.

In Ms. Henderson’s shop are photos of about 800 people in military uniforms. Her regular customers have brought photos of themselves when they were young or of family members who are now deceased.

She said, “I’m a patriot. But I praise those who worked for the country and those who sacrificed themselves for national policies, not the government.” She will continue to fight for compensation for the downwinders.

Steven Simon, head of the Dosimetry Unit at the Radiation Epidemiology Branch of the National Cancer Institute: Winds disperse radioactive particles

To obtain more information on nuclear fallout in the United States, the Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Steven Simon, head of the Dosimetry Unit at the Radiation Epidemiology Branch of the National Cancer Institute. He has written reports on nuclear tests conducted at the test site in Nevada and been involved in research projects on exposure doses in the Marshall Islands in the Pacific Ocean and Semipalatinsk in the former Soviet Union.

It’s surprising that nuclear fallout spread over such a wide range as 100 nuclear tests were being conducted in the atmosphere in Nevada.

This is because a huge amount of highly radioactive dust was blown into the air when a fireball touched the ground in an experiment where a bomb exploded near the ground. In Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the explosions were 600 meters above the ground, and there wasn’t much fallout. This is part of the difference.

Large particles such as dirt fell relatively near the hypocenter, but little particles were blown by the wind and fell back onto the ground when it rained, and hot spots were made.

The NCI report refers to the way people drink milk. Does a daily habit like this have a significant impact on people’s internal exposure to radiation?

The thyroid is susceptible to the effect of radiation. When cows eat a lot of grass that is laced with fallout, radioactive iodine, which is water-soluble, is concentrated in the milk. The half-life of iodine-131 is eight days. Among those who lived in the same area, or among people who were children when nuclear tests were being conducted in the 1950s, the more fresh milk they drank, the more radioactive iodine was taken into their thyroids.

You also give risk assessments for thyroid cancer in this respect.

In the absence of any fallout exposure, about 400,000 people would develop thyroid cancer in their lifetimes. We added about 49,000 because of fallout.

That’s a lot.

It’s natural for people to worry, but let me stress that there is great uncertainty when it comes to statistics. In this day and age, 40 percent of the population die from cancer. There are many causes of cancer and there is no telling what the cause is in each case. It is like trying to hear what I say in a low voice in a noisy place. You can’t hear me because there’s too much noise in the background. And this wasn’t exposure to high doses of radiation and it happened decades ago. The exact cause can’t be known.

Is radioactive iodine the only problem?

Fallout from nuclear tests conducted by the former Soviet Union fell onto the ground after floating in the stratosphere for about one year. Even though it’s a smaller amount than in Nevada, radioactive cesium has been found in the eastern part of the United States. Fallout has spread around the world.

The Radiation Exposure Compensation Act: 18,550 victims identified, lump sums provided

The United States conducted 210 nuclear tests in the atmosphere before it signed the Partial Test Ban Treaty (PTBT) in 1963. About 100 of them were carried out at a nuclear test site in Nevada. Responding to complaints from people living in the vicinity and soldiers involved in the testing that the tests did harm to their health, the Radiation Exposure Compensation Act (RECA) was enacted in 1990.

RECA covers people who lived in the downwind affected area, who were engaged in nuclear tests, and who worked in uranium mines or in the process of refining it. If an individual who lived in the downwind area comes down with a designated disease, including breast cancer, that person can receive a lump sum of 50,000 dollars (5.2 million yen) if his or her application is accepted. According to the Department of Justice, 18,550 out of 23,233 compensation applications from those living in the affected area were accepted by February 2015.

But there are many conditions which conflict with the reality of nuclear tests. Only parts of Nevada, Arizona, and Utah have been designated as a downwind affected area, and Idaho is not included.

Some politicians are making bipartisan efforts with a view to revising the law. Lindsay Nothern, a secretary to Michael Crapo, a Republican senator from Idaho, is in charge of this issue at a Boise office. Mr. Nothern stressed that there is a lack of understanding that this is a nationwide problem. He added that politicians from the eastern part of the country have little interest in this issue and that efforts are being made to bring better understanding to all lawmakers.

(Originally published on June 19, 2016)