On Nehru and Books, in the Nuclear Age

Jan. 27, 2017

by Nassrine Azimi, Visiting Scholar, Terasaki Center for Japanese Studies, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA)

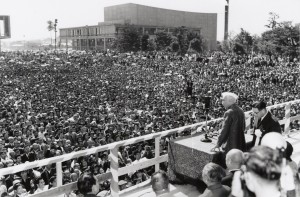

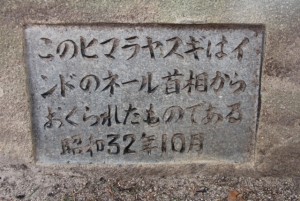

On the west side of the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima stands a tall, stately Himalayan cedar, gift of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of indpendent India. Nehru had visited Hiroshima in October 1957, among the first foreign dignitaries to pay his respects at the Cenotaph for A-bomb Victims, the heart of the Memorial Park. On reaching town from the Iwakuni U.S. naval air station, where he had landed, he had been welcomed by thousands of flag-waving school children.

I have often sat near that magnificent tree, a species native to Kashmir, in northern India, said to be the birthplace of Nehru’s ancestors. Despite his ambiguous stance on India’s nuclear program, which he had condoned, Nehru always spoke of his visit to Hiroshima as a ‘pilgrimage’ and in the hearts of Hiroshima citizens he continues to hold a very special place. The Japanese also never forgot his courage and support after WWII, in their own quest for international recognition.

Last month on a trip to India, and as part of an on-going research for a book on leaders who have shaped 20th century Asia, I went to visit the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library in New Delhi. The image I carried in my childhood of this iconic figure was that of the freedom fighter in his trademark homespun cotton khadi, sitting at the foot of his mentor Mahatma Gandhi. After independence, it was of the charismatic, intelligent representative of his country abroad. This time I came to learn more of Nehru the man, one who had given up so much personally, to fight for India. Raised in luxury in his father’s vast estates and educated by Scottish and English tutors, Nehru studied law at Cambridge University. Yet from the early 1920s he was to abandon this privileged cocoon, to embrace India’s quest for freedom. He would, in the process, languish almost 10 years in the prisons of the British Raj.

I discovered that Nehru had survived jail, in large part, thanks to books.

From his first incarceration in December 1921, in Lucknow, the outgoing, refined Nehru dealt with being a political prisoner—its oppression, injustice, boredom and humiliation—by reading and writing (he also spun cotton and gardened). He later wrote that long periods in prison were “apt to make one either a mental and physical wreck or a philosopher.” Through self-discipline he became a philosopher. The scope of his readings was impressive—from the Upanishads to Plato, from Iranian and Chinese history to the French and Bolshevik revolutions, from books on language, ethics and politics to the origins of Hinduism and Buddhism, and the destiny of many world figures—he read just about everything he was allowed to read.

It was during confinement, too, that Nehru wrote the three major books that came to articulate and define not just his intellectual legacy, but the foundations of his future governance of India.

The first, written from 1930 to 1933 in between political campaigning and jail sentences, was the 1196-page Glimpses of World History, a sprawling effort to think through 6000 years of human civilization and the prominent figures that had shaped it. The book was a collection of 196 letters to his beloved daughter Indira—some erudite, others disjointed wanderings of an open-minded humanist. Long before debates on globalization, working on this book was maybe what grounded in Nehru a universalist, secular, optimistic view of history, providing impetus for his ideas on the Non-Aligned Movement.

The second book, written between 1934 and 1935 while he served his seventh prison term, was the more personal autobiography. This time Nehru’s musing are more private, the tone graver. Repeated jail sentences had taken a toll. Family tragedies had struck. Across India itself there was despair. Yet once out of prison Nehru bounced back, reprising his travels across the length and breath of the country, seeing firsthand the misery and poverty of the Indian village dweller. It was as if working on each book somehow prepared him better, to calibrate his actions as a leader.

By the time Nehru was back in prison for his ninth jail term, in 1942, he had a deeper grasp of the magnitude of India’s problems—its crippling poverty after 200 years of British rule, its complex mosaic of peoples and religions, the weight of its caste system and sectarian tensions. For almost two years he just read. Then, from April to September 1944, he wrote his third major book, my favorite, The Discovery of India. He dedicated it to his co-prisoners in Ahmadnagar, many like him key figures of the independence movement and disciples of Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent civil disobedience campaign. Nehru’s own cell-mate was no other than Maulana Abel Kalam Azad, the renowned muslim scholar and the first education minister of independent India. He wrote of these learned companions as a remarkable, if impromptu, editorial board, helping further refine his political vision.

After The Discovery of India Nehru would not write much: in 1945 he was released for the last time by the British, stepping into the whirlwind of independence, the double tragedies of partition and Gandhi’s assassination, and 16 years of premiership. The time for writing books was behind him—he would later jokingly praise British prisons, for at least giving him time, to read and write.

If the spirit animating the Indian independence movement was Mahatma Gandhi’s great legacy, it was Nehru and his companions who led the charge of bringing an ancient but humiliated country into statehood. Nehru’s broad, eclectic, disciplined reading and writing were to be foundational stones in this transition. Like that other leader Barack Obama, Nehru had formed, in the company of books and the wisdom of the ages, the very core of his personal and political convictions.

The foundations of India’s democracy today (so much of it still lacking or under threat in other countries), its commitment to federalist principles, its secularism, its adherence to the international order and the rule of law, its open-minded stance vis-à-vis science, technology and basic education, its pride in its ancient history compatible with a modern, future-oriented outlook—many of these are Nehru’s legacies. Surely the task of India’s transformation was simply too great for any single individual or even generation. Nehru did not always succeed. The scholar David Malone, a former Canadian High Commissioner to India, has rightly written that ‘Time and history are on India's side as it struggles to recover from several centuries of foreign domination and its consequences’ but monumental obstacles remain: public infrastructure, despite decades of efforts, is woefully weak. The dire situation of the environment is daunting, a heavy price for the industrialization Nehru so unconditionally embraced (throughout my weeklong stay a dark, thick layer of pollution never lifted from New Delhi). Income inequality, rising, is even more marked than the global average, with the top 1% of the population holding 58% of the country’s wealth, an insult to the profound convictions carried by both Gandhi and Nehru. Nuclear tensions in the region remain unacceptably high. And India’s staggering overpopulation is a formidable challenge by any measure.

Yet as distant as Nehru’s dream of India may still seem, it is unfailingly alive.

I was reminded of just how alive, during the visit to his Memorial Museum, the prime minister’s official residence until his death in 1964. The richness of mind and a certain simple elegance, of the man who had occupied those quarters, was visible everywhere. An endless flow of beaming school children kept passing by, dressed in neat, crisp uniforms, preening over each other’s shoulders to read the titles of some of the library collections. Nehru’s books, lovingly kept, are remarkable in their diversity but his learning was not just theoretical. It is said that he knew hundreds of trees and flowers by name, had crisscrossed India on foot, and so loved animals that he had a small zoo built at home (in 1949 Nehru had also offered a small elephant to Tokyo’s Ueno Zoo, forever endearing himself to Japanese children). Years after Nehru’s death, his supporters built a planetarium on the grounds of the residence, to honor his unmitigated enthusiasm for science and the discovery of the universe.

Young students often ask me if reading is important anymore. The life and work of Nehru is one proof, that it is. In his struggle to help remake India Nehru translated knowledge and erudition into statecraft, cautioning us amply, about the dangers of ignorance. “There is nothing more horrifying than stupidity in action” he wrote. His commitment to universal values was genuine, and his vision of the human race as one single community ahead of his time. No wonder he understood so well, the symbolism of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. To the United Nations General Assembly in 1960 he quoted from another son of India, his role-model the Buddha “…the only real victory was one in which all were equally victorious and there was defeat for no one” he said. In this nuclear age of too many cantankerous, shortsighted and tweeting leaders, Nehru’s example of wisdom, erudition and caution, at the service of his compatriots, cannot be more compelling, or more urgent to emulate. In the words of my Indian friend Abha Narain Lambah, a former lecturer at UNITAR programs in Hiroshima, Nehru’s ideas were perhaps ‘too early for his times…and even for ours’.

Nassrine Azimi

Currently a visiting scholar at the Terasaki Center for Japanese Studies, University of California, in Los Angeles (UCLA). Born in Iran in 1959, Swiss citizen. Earned a master’s degree in international affairs from the Graduate Institute in Geneva, a second master’s degree from Geneva University’s Institute of Architecture, and a doctorate in cultural studies from Hiroshima University. Joined the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) in 1986. After serving as chief of UNITAR’s New York office, became the first director of its new Hiroshima office in 2003. Stepped down in 2009, now serves as its senior advisor. In 2011 co-founded and now co-coordinates Green Legacy Hiroshima (http://www.unitar.org/greenlegacyhiroshima), an initiative to send around the world seeds and seedlings from trees that survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Has written numerous opinion pieces in the International New York Times and other publications, including on Hiroshima’s efforts to bring about peace, and on the aftermath of the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima. Her most recent book, Last Boat to Yokohama, was released in May 2015. She is now preparing a book on the role of American specialists who helped protect Japan’s cultural property in the aftermath of WWII.

On the west side of the Peace Memorial Park in Hiroshima stands a tall, stately Himalayan cedar, gift of Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of indpendent India. Nehru had visited Hiroshima in October 1957, among the first foreign dignitaries to pay his respects at the Cenotaph for A-bomb Victims, the heart of the Memorial Park. On reaching town from the Iwakuni U.S. naval air station, where he had landed, he had been welcomed by thousands of flag-waving school children.

I have often sat near that magnificent tree, a species native to Kashmir, in northern India, said to be the birthplace of Nehru’s ancestors. Despite his ambiguous stance on India’s nuclear program, which he had condoned, Nehru always spoke of his visit to Hiroshima as a ‘pilgrimage’ and in the hearts of Hiroshima citizens he continues to hold a very special place. The Japanese also never forgot his courage and support after WWII, in their own quest for international recognition.

Last month on a trip to India, and as part of an on-going research for a book on leaders who have shaped 20th century Asia, I went to visit the Nehru Memorial Museum and Library in New Delhi. The image I carried in my childhood of this iconic figure was that of the freedom fighter in his trademark homespun cotton khadi, sitting at the foot of his mentor Mahatma Gandhi. After independence, it was of the charismatic, intelligent representative of his country abroad. This time I came to learn more of Nehru the man, one who had given up so much personally, to fight for India. Raised in luxury in his father’s vast estates and educated by Scottish and English tutors, Nehru studied law at Cambridge University. Yet from the early 1920s he was to abandon this privileged cocoon, to embrace India’s quest for freedom. He would, in the process, languish almost 10 years in the prisons of the British Raj.

I discovered that Nehru had survived jail, in large part, thanks to books.

From his first incarceration in December 1921, in Lucknow, the outgoing, refined Nehru dealt with being a political prisoner—its oppression, injustice, boredom and humiliation—by reading and writing (he also spun cotton and gardened). He later wrote that long periods in prison were “apt to make one either a mental and physical wreck or a philosopher.” Through self-discipline he became a philosopher. The scope of his readings was impressive—from the Upanishads to Plato, from Iranian and Chinese history to the French and Bolshevik revolutions, from books on language, ethics and politics to the origins of Hinduism and Buddhism, and the destiny of many world figures—he read just about everything he was allowed to read.

It was during confinement, too, that Nehru wrote the three major books that came to articulate and define not just his intellectual legacy, but the foundations of his future governance of India.

The first, written from 1930 to 1933 in between political campaigning and jail sentences, was the 1196-page Glimpses of World History, a sprawling effort to think through 6000 years of human civilization and the prominent figures that had shaped it. The book was a collection of 196 letters to his beloved daughter Indira—some erudite, others disjointed wanderings of an open-minded humanist. Long before debates on globalization, working on this book was maybe what grounded in Nehru a universalist, secular, optimistic view of history, providing impetus for his ideas on the Non-Aligned Movement.

The second book, written between 1934 and 1935 while he served his seventh prison term, was the more personal autobiography. This time Nehru’s musing are more private, the tone graver. Repeated jail sentences had taken a toll. Family tragedies had struck. Across India itself there was despair. Yet once out of prison Nehru bounced back, reprising his travels across the length and breath of the country, seeing firsthand the misery and poverty of the Indian village dweller. It was as if working on each book somehow prepared him better, to calibrate his actions as a leader.

By the time Nehru was back in prison for his ninth jail term, in 1942, he had a deeper grasp of the magnitude of India’s problems—its crippling poverty after 200 years of British rule, its complex mosaic of peoples and religions, the weight of its caste system and sectarian tensions. For almost two years he just read. Then, from April to September 1944, he wrote his third major book, my favorite, The Discovery of India. He dedicated it to his co-prisoners in Ahmadnagar, many like him key figures of the independence movement and disciples of Mahatma Gandhi’s non-violent civil disobedience campaign. Nehru’s own cell-mate was no other than Maulana Abel Kalam Azad, the renowned muslim scholar and the first education minister of independent India. He wrote of these learned companions as a remarkable, if impromptu, editorial board, helping further refine his political vision.

After The Discovery of India Nehru would not write much: in 1945 he was released for the last time by the British, stepping into the whirlwind of independence, the double tragedies of partition and Gandhi’s assassination, and 16 years of premiership. The time for writing books was behind him—he would later jokingly praise British prisons, for at least giving him time, to read and write.

If the spirit animating the Indian independence movement was Mahatma Gandhi’s great legacy, it was Nehru and his companions who led the charge of bringing an ancient but humiliated country into statehood. Nehru’s broad, eclectic, disciplined reading and writing were to be foundational stones in this transition. Like that other leader Barack Obama, Nehru had formed, in the company of books and the wisdom of the ages, the very core of his personal and political convictions.

The foundations of India’s democracy today (so much of it still lacking or under threat in other countries), its commitment to federalist principles, its secularism, its adherence to the international order and the rule of law, its open-minded stance vis-à-vis science, technology and basic education, its pride in its ancient history compatible with a modern, future-oriented outlook—many of these are Nehru’s legacies. Surely the task of India’s transformation was simply too great for any single individual or even generation. Nehru did not always succeed. The scholar David Malone, a former Canadian High Commissioner to India, has rightly written that ‘Time and history are on India's side as it struggles to recover from several centuries of foreign domination and its consequences’ but monumental obstacles remain: public infrastructure, despite decades of efforts, is woefully weak. The dire situation of the environment is daunting, a heavy price for the industrialization Nehru so unconditionally embraced (throughout my weeklong stay a dark, thick layer of pollution never lifted from New Delhi). Income inequality, rising, is even more marked than the global average, with the top 1% of the population holding 58% of the country’s wealth, an insult to the profound convictions carried by both Gandhi and Nehru. Nuclear tensions in the region remain unacceptably high. And India’s staggering overpopulation is a formidable challenge by any measure.

Yet as distant as Nehru’s dream of India may still seem, it is unfailingly alive.

I was reminded of just how alive, during the visit to his Memorial Museum, the prime minister’s official residence until his death in 1964. The richness of mind and a certain simple elegance, of the man who had occupied those quarters, was visible everywhere. An endless flow of beaming school children kept passing by, dressed in neat, crisp uniforms, preening over each other’s shoulders to read the titles of some of the library collections. Nehru’s books, lovingly kept, are remarkable in their diversity but his learning was not just theoretical. It is said that he knew hundreds of trees and flowers by name, had crisscrossed India on foot, and so loved animals that he had a small zoo built at home (in 1949 Nehru had also offered a small elephant to Tokyo’s Ueno Zoo, forever endearing himself to Japanese children). Years after Nehru’s death, his supporters built a planetarium on the grounds of the residence, to honor his unmitigated enthusiasm for science and the discovery of the universe.

Young students often ask me if reading is important anymore. The life and work of Nehru is one proof, that it is. In his struggle to help remake India Nehru translated knowledge and erudition into statecraft, cautioning us amply, about the dangers of ignorance. “There is nothing more horrifying than stupidity in action” he wrote. His commitment to universal values was genuine, and his vision of the human race as one single community ahead of his time. No wonder he understood so well, the symbolism of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. To the United Nations General Assembly in 1960 he quoted from another son of India, his role-model the Buddha “…the only real victory was one in which all were equally victorious and there was defeat for no one” he said. In this nuclear age of too many cantankerous, shortsighted and tweeting leaders, Nehru’s example of wisdom, erudition and caution, at the service of his compatriots, cannot be more compelling, or more urgent to emulate. In the words of my Indian friend Abha Narain Lambah, a former lecturer at UNITAR programs in Hiroshima, Nehru’s ideas were perhaps ‘too early for his times…and even for ours’.

Nassrine Azimi

Currently a visiting scholar at the Terasaki Center for Japanese Studies, University of California, in Los Angeles (UCLA). Born in Iran in 1959, Swiss citizen. Earned a master’s degree in international affairs from the Graduate Institute in Geneva, a second master’s degree from Geneva University’s Institute of Architecture, and a doctorate in cultural studies from Hiroshima University. Joined the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR) in 1986. After serving as chief of UNITAR’s New York office, became the first director of its new Hiroshima office in 2003. Stepped down in 2009, now serves as its senior advisor. In 2011 co-founded and now co-coordinates Green Legacy Hiroshima (http://www.unitar.org/greenlegacyhiroshima), an initiative to send around the world seeds and seedlings from trees that survived the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. Has written numerous opinion pieces in the International New York Times and other publications, including on Hiroshima’s efforts to bring about peace, and on the aftermath of the accident at the nuclear power plant in Fukushima. Her most recent book, Last Boat to Yokohama, was released in May 2015. She is now preparing a book on the role of American specialists who helped protect Japan’s cultural property in the aftermath of WWII.