Gray area: Effects of exposure to low-level radiation, Part 7 [3]

Nov. 5, 2016

The benefits and risks of medical exposure to radiation

by Yumi Kanazaki and Yota Baba, Staff Writers

To what extent is human health affected by exposure to very low levels of radiation? This issue is being examined based on research into Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-bomb survivors and the radiation contamination caused by the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). However, low-level radiation exposure, the type of radiation exposure we are most likely to experience, is exposure through medical examinations, such as the computed tomography (CT) scan. Although the CT scan is very helpful in the early detection of diseases, the frequency of radiation exposure from CT scanning is high, particularly in Japan. But efforts to reduce medical exposure have only just begun. This article explores these initiatives and the problems involved in reducing medical exposure.

Managing radiation exposure to CT scans

Efforts to prevent exposure to unnecessary radiation (X-rays) resulting from CT scanning are being made, led by the Japan Association of Radiological Technologists. In this work to date, reduction targets have been set, and 68 hospitals in the nation which satisfied certain conditions have been authorized as a hospital seeking to reduce medical radiation exposure. In the Chugoku Region, there are four such hospitals: Miyoshi Central Hospital (in Miyoshi), the Kanmon Medical Center (in Shimonoseki), Kurashiki Central Hospital (in Kurashiki) and Tsuyama Chuo Hospital (in Tsuyama).

In Miyoshi Central Hospital, which obtained this certification in 2008, doctors and radiological technologists set exposure dosages for each part of the body, and have presented them on the hospital’s website. “The higher the exposure dosage, the clearer the scanned image. But at the same time, the risk of radiation exposure also increases. It’s vital to minimize this radiation exposure to levels that are only necessary for obtaining a diagnosis,” said Mikio Ueno, the head of the hospital’s radiological technologists. “With some exceptions, radiation dosages at our hospital were reduced to 60 to 70 percent of the reduction target values set by the Japan Association of Radiological Technologists.”

For children’s CT scans, in particular, in which the radiation dosage must be kept as low as possible, scanning conditions were carefully set in line with the child’s age. In addition, one of the radiological technologists obtained a qualification for the association’s accredited radiation exposure counselor with a view to providing adequate explanation about the CT scan to patients. The hospital also provides an X-ray examination notebook, in which the history of the patient’s entire medical exposure is recorded, if a patient would like one. Regarding the management of medical equipment, a periodical check is carried out using a dosimeter to eliminate errors between the exposure dosage displayed on the CT monitor and the actual measurement data.

It would seem, however, that patients’ interest in radiation exposure is not particularly keen. Each year only a few patients ask doctors to explain the risks associated with radiation exposure. Although there are some patients who have CT scans every year to monitor the possible recurrence of cancer and keep a record of accumulated radiation dosages exceeding 200 mSv in their notebooks, the number of X-ray examination notebooks that have been issued to patients over the past eight years is less than 100.

Miyoshi Central Hospital provides explanations about radiation exposure only when requested by a patient. “The explanation should be given every time an examination is carried out. However, due to the limited number of medical staff, it’s impossible for us to provide a full explanation to every patient,” said Mr. Ueno. The hospital staff are seeking an effective way to address this issue, given the gap between the ideal and the reality, to satisfy the explanation and agreement of informed consent.

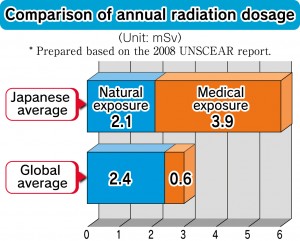

Among advanced nations, medical exposure is especially high in Japan. According to the Nuclear Research Safety Association, Japan’s average medical exposure is 3.9 mSv, exceeding the radiation level of 2.1 mSv which is emitted from the surface of the earth or is contained in food products.

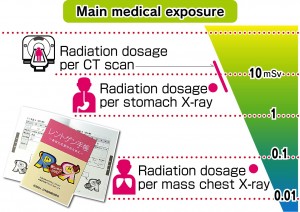

Medical exposure dosages vary according to the type of examinations. Exposure dosages from chest X-rays are about 0.1 mSv or less, but the dosages from a CT scan can exceed 10 mSv. In some cases, the exposure dosages of people who frequently have CT scans can exceed 100 mSv over a period of five years, which is the upper limit for occupational exposure.

However, as the early detection of diseases benefits those being examined, no legal limit has been set for medical exposure levels. But because radiation dosages are extremely high in some hospitals, the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) urges each member country to take measures to reduce the exposure dosages.

In Japan, the Japan Network for Research and Information on Medical Exposures (J-RIME) was formed in 2010 by various medical- and radiation-related academic entities. Since people’s awareness of radiation exposure has increased since the nuclear accident in Fukushima, diagnostic reference levels (DRLs) were set in June 2015.

The DRLs were set based on radiation dosage data from the 443 medical facilities in Japan which responded to the survey on medical exposure, and the data shows that 75% of the respondents keep their exposure dosages below the DRLs. A medical institution whose radiation dosages are above the DRLs will be urged to review its allowable limit. However, conforming to the DRLs is not binding, and therefore, the reduction of exposure dosages is left up to the self-supporting efforts of each medical institution.

Interview with Kazuo Awai, professor of diagnostic radiology at Hiroshima University

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Kazuo Awai, a professor of diagnostic radiology at the Institute of Biomedical & Health Sciences of Hiroshima University’s Graduate School who was involved in setting the diagnostic reference levels (DRLs), about the current situation and the problems associated with reducing medical exposure.

Why is medical exposure so frequent in Japan?

It is because there are 100 CT scanning units available for every one million people. This means that medical equipment which uses radiation has become particularly widespread in Japan among advanced nations, and people can receive medical examinations at a relatively low cost. Medical examinations also have the great advantage of detecting even a small carcinogenic tumor at an early stage of development.

The problem, however, is that the patient’s risk of receiving higher levels of radiation exposure increases, more than necessary, as a result of the examination. Until now there has been no widely recognized index, and so the exposure dosages have varied depending on each medical institution. They have also varied depending on the awareness and knowledge of radiological technologists and doctors regarding radiation exposure.

Do you think that the DRLs will help to reduce radiation dosages?

Because optimal radiation dosages are different from person to person depending on their body size, the DRLs serve only as a reference standard and are not therefore binding. But the DRLs can also be used as a base to examine whether a particular radiation dosage used by a hospital is high or not. The DRLs are still not widely familiar, but they are becoming more and more known among doctors and radiological technologists through seminars.

What do you think about the merits and risks of medical examinations involving radiation exposure?

I cannot say that CT scans are safe and do not increase the risk of a patient developing cancer. However, the follow-up surveys of the Hiroshima A-bomb survivors show that the possibility of a single CT scan causing cancer is extremely low. I’d also like people to know the merits of CT scans.

To give an example, CT scans of the liver are very useful for colorectal cancer patients whose cancer may eventually spread to the liver. Colorectal cancer patients are usually elderly and, if they are to develop another cancer as a consequence of having the CT scan, it would be after they get much older. It would be worse for the elderly patients to succumb to cancer within only a few years due to the colorectal cancer spreading to the liver rather than not undergoing a CT scan out of fear of being exposed to radiation.

Are there any cases in which people should be cautious about having CT scans?

For lung cancer, for example, it is highly recommended that a patient who is a heavy smoker and is already 50 years or older, have a CT scan. But it is an unfortunate fact that some non-smokers who are as young as in their 30s and 40s also undergo CT scans. Medical check-up institutions should therefore not accede to their request. The medical institutions should not put priority on their profits. I think it is necessary to establish guidelines for some typical diseases to indicate in which cases CT scans would be of benefit to the patients. If CT scans are used for every case, patients will be unnecessarily exposed to radiation.

CT scans for children are a high risk to their health and are a cause for concern.

The younger the patients, the more susceptible they are to the potential of being affected by radiation. There are, however, some cases where parents request that doctors conduct CT scans for their children. But as patients and their families cannot accurately determine the necessity of having CT scans, the doctor must decide what to do. As to whether a CT scan ought to be used for a patient who has suffered a severe bruise to the head, there are some reliable published theses overseas providing the criteria for such examinations. These areas of knowledge and the issues concerning children’s radiation exposure should be shared among doctors.

Do you think doctors are providing adequate explanations for their patients?

I cannot say yes. But the reality is that doctors don’t have enough time to do so because they have a lot of patients to examine. However, that cannot be said to be an appropriate reason for not providing adequate explanations to patients, and if it is difficult to adequately explain to a patient about radiation exposure in person, doctors can use videos which the patient can watch while waiting to see the doctor.

However, the main reason that doctors are not providing adequate explanations is the fact that they did not receive sufficient instruction concerning the risks associated with medical examinations and treatments which use radiation at medical school. To address this problem, Hiroshima University has revised its curriculum for its second-year students to include risks associated with medical examinations and treatments, and I think further education should be provided at the post-graduate level.

In the United States, the histories of medical exposure for each individual are stored and managed, for example, by entering the exposure dosage in an electronic medical record. Is it possible to adopt such a system in Japan?

As the management of medical exposure data does not create any revenue for medical institutions, the system would take some time to be introduced. However, Hiroshima University Hospital is now working on establishing a system to manage and record accumulative radiation exposure dosages of patients who undergo CT scans, chest X-ray tests, and angiographic examinations. There are, however, tens of thousands of pieces of data for just the CT scanning alone, and it would be impossible to manage them manually. So we have not yet reached the stage where we can release information and data concerning the examinations and tests to each patient.

In addition, it costs tens to hundreds of million yen to introduce this management system. If the needs of the patients increase or if, for example, a hospital that manages the medical exposure can assess a higher medical services fee, the awareness of medical exposure management will spread more widely.

Radiation exposure risk is higher in younger patients

The effects of low levels of radiation resulting from medical examinations and treatments are now becoming clearer as a result of research on young people who are susceptible to the effects of radiation.

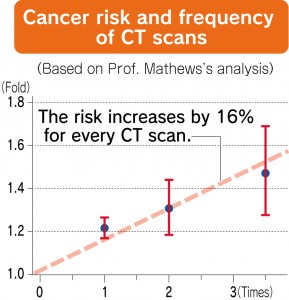

John Mathews, a professor emeritus of epidemiology at the University of Melbourne, Australia, monitored 680,000 people who underwent CT scans between the ages of 0 and 19 between 1985 and 2005 in Australia. The average number of years these people were monitored by the end of 2007 was 9.5 years. Compared to some 10 million people who had no record of undergoing a CT scan during the same period, the incidence of cancers, such as brain cancer or leukemia, was higher by 24% in those who had received the CT scanning. If this number is applied to cancer incidence statistics, the annual current cancer incidence rate of 40 people per 100,000 people increases to 50 people per 100,000 people.

According to the follow-up survey, the effective dose which indicates the effects on the whole body is estimated to be 4.5 mSv for every CT scan, thus increasing the risk of getting cancer by 16% for every scan. And this risk tends to increase as the age at the time of the radiation exposure falls. For example, if a child under the age of five years old receives a head CT scan, the possibility of developing a brain cancer afterward increases three-fold.

This survey is criticized for not proving the cause and effect relationship because people don’t usually undergo a CT scan until they develop symptoms. For this reason, Dr. Mathews excluded cancer cases which developed within one year of the CT scan from his research in order to increase the reliability of the data. He stresses that medical institutions should consider the necessity of having CT scans more seriously and explain the reasons to young patients and their parents, if the patients have CT scans. Dr. Mathews also suggests that, especially in Japan, people should recognize the health risks to the general public resulting from medical exposure may be higher than the risks resulting from the radiation contamination caused by the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident.

(Originally published on November 5, 2016)

by Yumi Kanazaki and Yota Baba, Staff Writers

To what extent is human health affected by exposure to very low levels of radiation? This issue is being examined based on research into Hiroshima and Nagasaki A-bomb survivors and the radiation contamination caused by the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant, operated by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). However, low-level radiation exposure, the type of radiation exposure we are most likely to experience, is exposure through medical examinations, such as the computed tomography (CT) scan. Although the CT scan is very helpful in the early detection of diseases, the frequency of radiation exposure from CT scanning is high, particularly in Japan. But efforts to reduce medical exposure have only just begun. This article explores these initiatives and the problems involved in reducing medical exposure.

Managing radiation exposure to CT scans

Efforts to prevent exposure to unnecessary radiation (X-rays) resulting from CT scanning are being made, led by the Japan Association of Radiological Technologists. In this work to date, reduction targets have been set, and 68 hospitals in the nation which satisfied certain conditions have been authorized as a hospital seeking to reduce medical radiation exposure. In the Chugoku Region, there are four such hospitals: Miyoshi Central Hospital (in Miyoshi), the Kanmon Medical Center (in Shimonoseki), Kurashiki Central Hospital (in Kurashiki) and Tsuyama Chuo Hospital (in Tsuyama).

In Miyoshi Central Hospital, which obtained this certification in 2008, doctors and radiological technologists set exposure dosages for each part of the body, and have presented them on the hospital’s website. “The higher the exposure dosage, the clearer the scanned image. But at the same time, the risk of radiation exposure also increases. It’s vital to minimize this radiation exposure to levels that are only necessary for obtaining a diagnosis,” said Mikio Ueno, the head of the hospital’s radiological technologists. “With some exceptions, radiation dosages at our hospital were reduced to 60 to 70 percent of the reduction target values set by the Japan Association of Radiological Technologists.”

For children’s CT scans, in particular, in which the radiation dosage must be kept as low as possible, scanning conditions were carefully set in line with the child’s age. In addition, one of the radiological technologists obtained a qualification for the association’s accredited radiation exposure counselor with a view to providing adequate explanation about the CT scan to patients. The hospital also provides an X-ray examination notebook, in which the history of the patient’s entire medical exposure is recorded, if a patient would like one. Regarding the management of medical equipment, a periodical check is carried out using a dosimeter to eliminate errors between the exposure dosage displayed on the CT monitor and the actual measurement data.

It would seem, however, that patients’ interest in radiation exposure is not particularly keen. Each year only a few patients ask doctors to explain the risks associated with radiation exposure. Although there are some patients who have CT scans every year to monitor the possible recurrence of cancer and keep a record of accumulated radiation dosages exceeding 200 mSv in their notebooks, the number of X-ray examination notebooks that have been issued to patients over the past eight years is less than 100.

Miyoshi Central Hospital provides explanations about radiation exposure only when requested by a patient. “The explanation should be given every time an examination is carried out. However, due to the limited number of medical staff, it’s impossible for us to provide a full explanation to every patient,” said Mr. Ueno. The hospital staff are seeking an effective way to address this issue, given the gap between the ideal and the reality, to satisfy the explanation and agreement of informed consent.

Among advanced nations, medical exposure is especially high in Japan. According to the Nuclear Research Safety Association, Japan’s average medical exposure is 3.9 mSv, exceeding the radiation level of 2.1 mSv which is emitted from the surface of the earth or is contained in food products.

Medical exposure dosages vary according to the type of examinations. Exposure dosages from chest X-rays are about 0.1 mSv or less, but the dosages from a CT scan can exceed 10 mSv. In some cases, the exposure dosages of people who frequently have CT scans can exceed 100 mSv over a period of five years, which is the upper limit for occupational exposure.

However, as the early detection of diseases benefits those being examined, no legal limit has been set for medical exposure levels. But because radiation dosages are extremely high in some hospitals, the United Nations Scientific Committee on the Effects of Atomic Radiation (UNSCEAR) urges each member country to take measures to reduce the exposure dosages.

In Japan, the Japan Network for Research and Information on Medical Exposures (J-RIME) was formed in 2010 by various medical- and radiation-related academic entities. Since people’s awareness of radiation exposure has increased since the nuclear accident in Fukushima, diagnostic reference levels (DRLs) were set in June 2015.

The DRLs were set based on radiation dosage data from the 443 medical facilities in Japan which responded to the survey on medical exposure, and the data shows that 75% of the respondents keep their exposure dosages below the DRLs. A medical institution whose radiation dosages are above the DRLs will be urged to review its allowable limit. However, conforming to the DRLs is not binding, and therefore, the reduction of exposure dosages is left up to the self-supporting efforts of each medical institution.

Interview with Kazuo Awai, professor of diagnostic radiology at Hiroshima University

The Chugoku Shimbun interviewed Kazuo Awai, a professor of diagnostic radiology at the Institute of Biomedical & Health Sciences of Hiroshima University’s Graduate School who was involved in setting the diagnostic reference levels (DRLs), about the current situation and the problems associated with reducing medical exposure.

Why is medical exposure so frequent in Japan?

It is because there are 100 CT scanning units available for every one million people. This means that medical equipment which uses radiation has become particularly widespread in Japan among advanced nations, and people can receive medical examinations at a relatively low cost. Medical examinations also have the great advantage of detecting even a small carcinogenic tumor at an early stage of development.

The problem, however, is that the patient’s risk of receiving higher levels of radiation exposure increases, more than necessary, as a result of the examination. Until now there has been no widely recognized index, and so the exposure dosages have varied depending on each medical institution. They have also varied depending on the awareness and knowledge of radiological technologists and doctors regarding radiation exposure.

Do you think that the DRLs will help to reduce radiation dosages?

Because optimal radiation dosages are different from person to person depending on their body size, the DRLs serve only as a reference standard and are not therefore binding. But the DRLs can also be used as a base to examine whether a particular radiation dosage used by a hospital is high or not. The DRLs are still not widely familiar, but they are becoming more and more known among doctors and radiological technologists through seminars.

What do you think about the merits and risks of medical examinations involving radiation exposure?

I cannot say that CT scans are safe and do not increase the risk of a patient developing cancer. However, the follow-up surveys of the Hiroshima A-bomb survivors show that the possibility of a single CT scan causing cancer is extremely low. I’d also like people to know the merits of CT scans.

To give an example, CT scans of the liver are very useful for colorectal cancer patients whose cancer may eventually spread to the liver. Colorectal cancer patients are usually elderly and, if they are to develop another cancer as a consequence of having the CT scan, it would be after they get much older. It would be worse for the elderly patients to succumb to cancer within only a few years due to the colorectal cancer spreading to the liver rather than not undergoing a CT scan out of fear of being exposed to radiation.

Are there any cases in which people should be cautious about having CT scans?

For lung cancer, for example, it is highly recommended that a patient who is a heavy smoker and is already 50 years or older, have a CT scan. But it is an unfortunate fact that some non-smokers who are as young as in their 30s and 40s also undergo CT scans. Medical check-up institutions should therefore not accede to their request. The medical institutions should not put priority on their profits. I think it is necessary to establish guidelines for some typical diseases to indicate in which cases CT scans would be of benefit to the patients. If CT scans are used for every case, patients will be unnecessarily exposed to radiation.

CT scans for children are a high risk to their health and are a cause for concern.

The younger the patients, the more susceptible they are to the potential of being affected by radiation. There are, however, some cases where parents request that doctors conduct CT scans for their children. But as patients and their families cannot accurately determine the necessity of having CT scans, the doctor must decide what to do. As to whether a CT scan ought to be used for a patient who has suffered a severe bruise to the head, there are some reliable published theses overseas providing the criteria for such examinations. These areas of knowledge and the issues concerning children’s radiation exposure should be shared among doctors.

Do you think doctors are providing adequate explanations for their patients?

I cannot say yes. But the reality is that doctors don’t have enough time to do so because they have a lot of patients to examine. However, that cannot be said to be an appropriate reason for not providing adequate explanations to patients, and if it is difficult to adequately explain to a patient about radiation exposure in person, doctors can use videos which the patient can watch while waiting to see the doctor.

However, the main reason that doctors are not providing adequate explanations is the fact that they did not receive sufficient instruction concerning the risks associated with medical examinations and treatments which use radiation at medical school. To address this problem, Hiroshima University has revised its curriculum for its second-year students to include risks associated with medical examinations and treatments, and I think further education should be provided at the post-graduate level.

In the United States, the histories of medical exposure for each individual are stored and managed, for example, by entering the exposure dosage in an electronic medical record. Is it possible to adopt such a system in Japan?

As the management of medical exposure data does not create any revenue for medical institutions, the system would take some time to be introduced. However, Hiroshima University Hospital is now working on establishing a system to manage and record accumulative radiation exposure dosages of patients who undergo CT scans, chest X-ray tests, and angiographic examinations. There are, however, tens of thousands of pieces of data for just the CT scanning alone, and it would be impossible to manage them manually. So we have not yet reached the stage where we can release information and data concerning the examinations and tests to each patient.

In addition, it costs tens to hundreds of million yen to introduce this management system. If the needs of the patients increase or if, for example, a hospital that manages the medical exposure can assess a higher medical services fee, the awareness of medical exposure management will spread more widely.

Radiation exposure risk is higher in younger patients

The effects of low levels of radiation resulting from medical examinations and treatments are now becoming clearer as a result of research on young people who are susceptible to the effects of radiation.

John Mathews, a professor emeritus of epidemiology at the University of Melbourne, Australia, monitored 680,000 people who underwent CT scans between the ages of 0 and 19 between 1985 and 2005 in Australia. The average number of years these people were monitored by the end of 2007 was 9.5 years. Compared to some 10 million people who had no record of undergoing a CT scan during the same period, the incidence of cancers, such as brain cancer or leukemia, was higher by 24% in those who had received the CT scanning. If this number is applied to cancer incidence statistics, the annual current cancer incidence rate of 40 people per 100,000 people increases to 50 people per 100,000 people.

According to the follow-up survey, the effective dose which indicates the effects on the whole body is estimated to be 4.5 mSv for every CT scan, thus increasing the risk of getting cancer by 16% for every scan. And this risk tends to increase as the age at the time of the radiation exposure falls. For example, if a child under the age of five years old receives a head CT scan, the possibility of developing a brain cancer afterward increases three-fold.

This survey is criticized for not proving the cause and effect relationship because people don’t usually undergo a CT scan until they develop symptoms. For this reason, Dr. Mathews excluded cancer cases which developed within one year of the CT scan from his research in order to increase the reliability of the data. He stresses that medical institutions should consider the necessity of having CT scans more seriously and explain the reasons to young patients and their parents, if the patients have CT scans. Dr. Mathews also suggests that, especially in Japan, people should recognize the health risks to the general public resulting from medical exposure may be higher than the risks resulting from the radiation contamination caused by the Fukushima nuclear power plant accident.

(Originally published on November 5, 2016)