The Key to a World without Nuclear Weapons, Part 3

Jan. 17, 2017

Part 3: Court ruled the atomic bombings violate international law

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

“The atomic bombings violate international laws.” This was the ruling finalized in 1963 by the Tokyo District Court in connection with the “A-bomb trial,” a lawsuit filed against the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Japan Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms received the original copy of this ruling and took over the lawsuit from Yasuhiro Matsui, a lawyer and the first president of the association. Mr. Matsui, who was from Sagishima Island, Mihara City (and died at the age of 85 in 2008), served as a proxy for the plaintiffs in this trial.

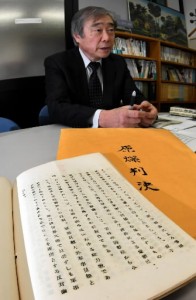

“Mr. Matsui would be glad to know that negotiations over a treaty to ban nuclear weapons will soon begin, but at the same time he might complain that ‘it has taken a long time’,” said Kenichi Okubo, 70, a lawyer and the secretary general of the association. As he opened the original copy of the ruling at his law firm in Tokorozawa, Saitama prefecture, he added, “There have already been several judicial rulings in which the use of nuclear weapons was judged to be illegal. Based on these rulings, we now have to create a treaty that will lead to the abolition of nuclear weapons.”

There is a reason that Mr. Okubo emphasizes the words “based on these rulings.” Countries which support a treaty to outlaw nuclear arms insist that one must be established because no such treaty that clearly prohibits nuclear weapons yet exists. On the other hand, there is the possibility that the nuclear weapon states could turn this situation to their advantage by insisting that “the use of nuclear weapons is not illegal” as long as a nuclear ban treaty is not ratified. This is why light should be shed on the judicial rulings that were made in the past.

The lawsuit over the atomic bombings was filed in 1955. As plaintiffs, a group of A-bomb survivors appealed that the U.S. bombings were illegal and called for compensation for their suffering from the Japanese government. Mr. Matsui, who based his activities in Tokyo after the war, became involved in this lawsuit by responding to an invitation from Shoichi Okamoto, who sought to have atomic and hydrogen bombs banned by bringing this case to court. After Mr. Okamoto’s death in 1958, Mr. Matsui took over and led the lawsuit.

Katsu Matsui, 63, Mr. Matsui’s eldest son and a resident of Nerima Ward, Tokyo, said, “My father must have been driven by his younger brother’s terrible experience of the atomic bombing.” His father’s younger brother, Yoshiomi (who died at the age of 81 in 2007), was buried alive beneath the building where he was living, about one kilometer from the hypocenter of the Hiroshima bombing. Yoshiomi later suffered from stomach cancer and rectal cancer.

Immediately after the atomic bombings, the Japanese government protested the U.S. actions, contending that the bombings were illegal. At the A-bomb trial, however, the government abruptly changed its stance and argued against the A-bomb survivors on the basis that there was actually no law to control the use of atomic bombs during World War II. The court ruling dismissed the plaintiffs’ claim for compensation, but admitted that the indiscriminate nature of the damage wrought by the atomic bombings and the inhumane nature of the radiation aftereffects of the atomic bombs were against the Hague Convention in addition to other international laws of war. Neither the A-bomb survivors nor the Japanese government appealed the court ruling.

Mr. Matsui believed that the ruling provided an opportunity to eliminate nuclear weapons. “If the use of an atomic bomb contravenes international law, it is legally reasonable to interpret the manufacturing, testing, and delivering of nuclear weapons as preparation for the use of nuclear weapons and therefore to have the manufacturing, testing, and delivering of them banned” (he said in his 1986 book entitled A-bomb Trial). During the hearing, Mr. Matsui advocated bringing this case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Some 40 years later, the efforts of the International Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms and other organizations bore fruit. At the ICJ hearing, citing the ruling of the A-bomb trial, the Republic of Nauru and other nations near the U.S. nuclear test sites in the Pacific insisted that the use of nuclear weapons is illegal. In 1996, the ICJ rendered an advisory opinion and mentioned that the Court cannot conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in an extreme circumstance of self-defense, in which the very survival of a State would be at stake. But at the same time, it also stated that the threat or use of nuclear weapons would “generally be contrary to the rules of international law.”

At the 1993 World Conference Against A & H Bombs, held in Hiroshima by the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs and other organizations, Mr. Matsui announced treaty guidelines for eliminating all nuclear weapons. He said in the charter that Hiroshima and Nagasaki became a hell on earth, and included a comprehensive ban on manufacturing and using nuclear weapons together with sanctions against violations. The Republic of Costa Rica is said to have referred to Mr. Matsui’s guidelines for the model ban treaty that it submitted to the United Nations in 1997. On the other hand, since the end of the war, the Japanese government has not mentioned clearly that the dropping of the atomic bombs was against international law. Furthermore, in 2016, Japan opposed the U.N. resolution to start negotiations on a treaty that would outlaw nuclear weapons.

Mr. Kenichi Okubo asks, “Will countries that are against the negotiations for a nuclear ban treaty ignore the judicial rulings?” He is convinced that if the A-bomb trial ruling and the opinion of the ICJ are valued, the conclusion of a treaty which outlaws nuclear arms would naturally be the outcome.

Keywords

A-bomb trial

In 1995, five A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki filed a lawsuit against the Japanese government seeking redress for damages caused by the atomic bombings because the Japanese government had waived its right to make claims against the United States under the San Francisco Peace Treaty. The court judged the atomic bombings illegal based on the principles of existing international law, which dictate that only military targets can be attacked and that unnecessary suffering must be avoided. The trial is known worldwide as the “Shimoda Case” in tribute to the late Ryuichi Shimoda, who was one of the plaintiffs. Mr. Shimoda lost five family members as a result of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

(Originally published on January 17, 2017)

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

“The atomic bombings violate international laws.” This was the ruling finalized in 1963 by the Tokyo District Court in connection with the “A-bomb trial,” a lawsuit filed against the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The Japan Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms received the original copy of this ruling and took over the lawsuit from Yasuhiro Matsui, a lawyer and the first president of the association. Mr. Matsui, who was from Sagishima Island, Mihara City (and died at the age of 85 in 2008), served as a proxy for the plaintiffs in this trial.

“Mr. Matsui would be glad to know that negotiations over a treaty to ban nuclear weapons will soon begin, but at the same time he might complain that ‘it has taken a long time’,” said Kenichi Okubo, 70, a lawyer and the secretary general of the association. As he opened the original copy of the ruling at his law firm in Tokorozawa, Saitama prefecture, he added, “There have already been several judicial rulings in which the use of nuclear weapons was judged to be illegal. Based on these rulings, we now have to create a treaty that will lead to the abolition of nuclear weapons.”

There is a reason that Mr. Okubo emphasizes the words “based on these rulings.” Countries which support a treaty to outlaw nuclear arms insist that one must be established because no such treaty that clearly prohibits nuclear weapons yet exists. On the other hand, there is the possibility that the nuclear weapon states could turn this situation to their advantage by insisting that “the use of nuclear weapons is not illegal” as long as a nuclear ban treaty is not ratified. This is why light should be shed on the judicial rulings that were made in the past.

The lawsuit over the atomic bombings was filed in 1955. As plaintiffs, a group of A-bomb survivors appealed that the U.S. bombings were illegal and called for compensation for their suffering from the Japanese government. Mr. Matsui, who based his activities in Tokyo after the war, became involved in this lawsuit by responding to an invitation from Shoichi Okamoto, who sought to have atomic and hydrogen bombs banned by bringing this case to court. After Mr. Okamoto’s death in 1958, Mr. Matsui took over and led the lawsuit.

Katsu Matsui, 63, Mr. Matsui’s eldest son and a resident of Nerima Ward, Tokyo, said, “My father must have been driven by his younger brother’s terrible experience of the atomic bombing.” His father’s younger brother, Yoshiomi (who died at the age of 81 in 2007), was buried alive beneath the building where he was living, about one kilometer from the hypocenter of the Hiroshima bombing. Yoshiomi later suffered from stomach cancer and rectal cancer.

Immediately after the atomic bombings, the Japanese government protested the U.S. actions, contending that the bombings were illegal. At the A-bomb trial, however, the government abruptly changed its stance and argued against the A-bomb survivors on the basis that there was actually no law to control the use of atomic bombs during World War II. The court ruling dismissed the plaintiffs’ claim for compensation, but admitted that the indiscriminate nature of the damage wrought by the atomic bombings and the inhumane nature of the radiation aftereffects of the atomic bombs were against the Hague Convention in addition to other international laws of war. Neither the A-bomb survivors nor the Japanese government appealed the court ruling.

Mr. Matsui believed that the ruling provided an opportunity to eliminate nuclear weapons. “If the use of an atomic bomb contravenes international law, it is legally reasonable to interpret the manufacturing, testing, and delivering of nuclear weapons as preparation for the use of nuclear weapons and therefore to have the manufacturing, testing, and delivering of them banned” (he said in his 1986 book entitled A-bomb Trial). During the hearing, Mr. Matsui advocated bringing this case to the International Court of Justice (ICJ).

Some 40 years later, the efforts of the International Association of Lawyers Against Nuclear Arms and other organizations bore fruit. At the ICJ hearing, citing the ruling of the A-bomb trial, the Republic of Nauru and other nations near the U.S. nuclear test sites in the Pacific insisted that the use of nuclear weapons is illegal. In 1996, the ICJ rendered an advisory opinion and mentioned that the Court cannot conclude definitively whether the threat or use of nuclear weapons would be lawful or unlawful in an extreme circumstance of self-defense, in which the very survival of a State would be at stake. But at the same time, it also stated that the threat or use of nuclear weapons would “generally be contrary to the rules of international law.”

At the 1993 World Conference Against A & H Bombs, held in Hiroshima by the Japan Council against Atomic and Hydrogen Bombs and other organizations, Mr. Matsui announced treaty guidelines for eliminating all nuclear weapons. He said in the charter that Hiroshima and Nagasaki became a hell on earth, and included a comprehensive ban on manufacturing and using nuclear weapons together with sanctions against violations. The Republic of Costa Rica is said to have referred to Mr. Matsui’s guidelines for the model ban treaty that it submitted to the United Nations in 1997. On the other hand, since the end of the war, the Japanese government has not mentioned clearly that the dropping of the atomic bombs was against international law. Furthermore, in 2016, Japan opposed the U.N. resolution to start negotiations on a treaty that would outlaw nuclear weapons.

Mr. Kenichi Okubo asks, “Will countries that are against the negotiations for a nuclear ban treaty ignore the judicial rulings?” He is convinced that if the A-bomb trial ruling and the opinion of the ICJ are valued, the conclusion of a treaty which outlaws nuclear arms would naturally be the outcome.

Keywords

A-bomb trial

In 1995, five A-bomb survivors in Hiroshima and Nagasaki filed a lawsuit against the Japanese government seeking redress for damages caused by the atomic bombings because the Japanese government had waived its right to make claims against the United States under the San Francisco Peace Treaty. The court judged the atomic bombings illegal based on the principles of existing international law, which dictate that only military targets can be attacked and that unnecessary suffering must be avoided. The trial is known worldwide as the “Shimoda Case” in tribute to the late Ryuichi Shimoda, who was one of the plaintiffs. Mr. Shimoda lost five family members as a result of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

(Originally published on January 17, 2017)