Peace Seeds: Teens in Hiroshima Sow Seeds of Peace (Part 42)

Mar. 16, 2017

Part 42: Young people from Fukushima live in Hiroshima, cherishing hometown but moving forward in life

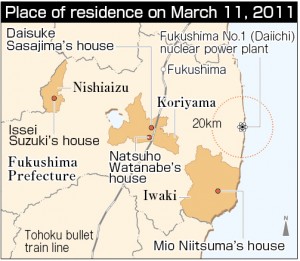

Do you recall what happened on March 11, 2011? A massive earthquake, hitting the top of the seven-point Japanese scale of seismic intensity, triggered a monstrous tsunami. The tsunami slammed northeastern Japan and precipitated an accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. Six years after the triple disaster, some 123,000 people have still not been able to return home.

Some of those who left Fukushima Prefecture to live in Hiroshima are now teens. There are various reasons why they made this move from their hometowns, including the fear of radiation and the desire to attend a university in Hiroshima. While their hometowns are still in their thoughts, they are moving forward with their lives.

The junior writers of the Chugoku Shimbun interviewed several of these young people. They told us that, although they felt anxious at first, they found friends who offered them support while treating them the same as other friends.

Mio Niitsuma, 17, resident of Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima: New friends provide emotional support

Under a clear blue sky, a gathering was held on the bank of the river opposite the A-bomb Dome on March 11. They were there to pray for the victims of the disaster in 2011. Mio Niitsuma, 17, and her mother Noriko, 50, attended the gathering for the first time. Mio moved from Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture to Hiroshima one year after the disaster. Now she is a second-year student at Koyohigashi Senior High School in Asakita Ward, Hiroshima. Though it is painful for her to recall what happened on that day, she has made up her mind to share her experience with others.

At the time, Mio was in fifth grade and in her classroom, preparing to return home, when the earthquake struck. The students huddled under their desks and waited for the tremors to subside. Her mother then arrived to pick her up and they went home. When she saw the television footage of the tsunami, she was stunned. She hadn’t known that the nuclear power plant, which would erupt in disaster the following day, was located about 45 kilometers from her home in the suburbs of Iwaki.

Afterward, her mother suggested that they move to Hiroshima so they wouldn’t have to worry about radiation. With support from her mother’s friends, they relocated to Hiroshima after Mio completed elementary school. She remembers feeling very lonely when her friends asked why she had to move so far away.

Still, she made new friends in Hiroshima, who helped her adjust. Mio says that she’s happy when chatting and laughing with her friends at school and that it was good she came to Hiroshima. She has decided to stay in Hiroshima in the future, too, but feels concern over the fact that people are starting to forget the nuclear disaster. She hopes that there will be no more nuclear accidents. She would like to work as a children’s nurse one day and tell them about her experience. (Nanaho Yamamoto, 17, and Kotoori Kawagishi, 14)

Daisuke Sasajima, 16, resident of Onomichi: Still wanting to go home

When his friends moved to other schools a year after the disaster, Daisuke Sasajima, now 16, was a fifth grader. At the time, Daisuke told them, “I won’t be leaving,” which meant, “I’ll always be here, so come back anytime.” But once he finished elementary school, he moved with his family to the city of Onomichi in Hiroshima Prefecture. Still, his love for his hometown of Koriyama, Fukushima has not dimmed.

Daisuke was at home when the earthquake occurred. Dishes, plates, and other things were scattered about in his house, and the water supply was shut off. The following day, he and his father went to a park and stood in line for five hours to get water. When they came home, his mother told them that there had been an explosion at the nuclear power plant. As he was unfamiliar with the subject of nuclear energy, he couldn’t comprehend what this meant.

School resumed in mid-April. To avoid being exposed to radiation, students had to wear long sleeves, long pants, and a mask, even in summer. A radiation meter was installed at the school. As a rising number of bags containing radioactive waste from decontamination work were piled on the school grounds, his friends moved away.

Daisuke has met supportive people in Onomichi. He is a first-year student at a high school in neighboring Okayama Prefecture. He has settled into his new life in Onomichi and its old townscape, and he enjoys playing with the cats in his neighborhood. “At the time, there was no choice but to leave Fukushima Prefecture. But part of me still wants to go back,” he said, expressing the mixed emotions he feels. (Ai Mizoue, 14, and Yui Morimoto, 13)

Natsuho Watanabe, 17, resident of Naka Ward, Hiroshima: Finding a sense of belonging

It was softball that helped Natsuho Watanabe, now 17, a sophomore at Hiroshima Jogakuin Senior High School, become more positive again. She left her home in Koriyama, Fukushima Prefecture two days after the disaster. It was a sad experience for her because she was unable to see her friends and say goodbye. She still cares about her friends from childhood, but she is now also committed to playing softball with her high school teammates and holds dreams for her future.

Natsuho was in fifth grade when the earthquake struck, and this experience made her feel very anxious. Water spilled out from her goldfish tank and she was so frightened, she couldn’t stop crying. She and her mother flew to Nagoya, where they heard the news about the accident at the nuclear power plant. Then they took a bullet train to her maternal grandparents’ home in Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture. After staying there for one year, they moved to Hiroshima when she entered junior high school.

Because she missed her friends so much, she vented her frustrations at her mother. There was a time, too, when she couldn’t bring herself to attend school. But the teacher in charge of the softball club, and the members of the team, invited her to join their practices. Then, in the autumn of her second year, she became one of the players in the starting lineup. She felt that the softball club was where she really belonged.

Now Natsuho is thinking about what she can do to help and she hopes to become a doctor. She wishes that her grandfather, who was a doctor, and her grandmother could witness her future. But they died in Koriyama after the nuclear accident. Smiling, she said, “Now I have twice as many friends as I once did, and good things have happened.” (Ishin Nakahara, 18)

Issei Suzuki, 20, resident of Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima: Encouraged by lives of Japanese immigrants to Hawaii

Issei Suzuki, 20, is a sophomore at the Hiroshima University of Economics, located in Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima. He and other students have been working on a project to promote exchanges between Japanese Hawaiians and young people in Hiroshima. He has been learning about the history of immigration and says, “I’ve been encouraged by those who lived courageous lives in a foreign country.” He moved from Nishiaizu, Fukushima Prefecture to Hiroshima two years ago.

He was not directly affected by the disaster that occurred when he was a second-year student in junior high school. But the situation there made the future of his mother’s job uncertain. So, in the autumn of his last year in junior high, his mother and his twin sister moved to Hiroshima, where his mother is originally from. Issei and his father remained behind in Fukushima. He tried to cherish every moment he could spend with his friends, since the disaster had taught him that there’s no telling what might happen in our lives.

But his father then died of illness. Issei moved to Hiroshima when he became a university student. In Hiroshima, though, he felt that some people didn’t have an accurate understanding of the effects of the nuclear accident. They hear about high radiation levels in one part of the Fukushima Prefecture and get the mistaken idea that the entire prefecture is contaminated. “Just because I’m from the disaster-hit area, people tend to feel pity for me,” he said. “But it’s better if people here give us their encouragement, like the way Hiroshima recovered from the atomic bombing.”

Aya Miura, head of Asuchika, a group of evacuees living in Hiroshima: Understand that each person’s circumstances are different

How should we treat the children who have moved from Fukushima Prefecture? The junior writers also interviewed Aya Miura, the head of Asuchika, a group for people who relocated to Hiroshima after the triple disaster that occurred in northeastern Japan. Below are some of her thoughts.

Children came here with their parents after the parents were forced to make the agonizing decision to move away from Fukushima Prefecture. Now that six years have passed since the disaster, the children have gotten used to their new lives in the Hiroshima area, with new friends and new schools, and they’re moving forward with their education. The advantage for children is that they can find a new circle of friends no matter their parents’ employment or their living environment.

But casual comments can be hurtful to them, such as “How long will you stay here?” or “When will you go back to Fukushima?” They may have misgivings, like “Maybe I shouldn’t stay here” or “Maybe I should go back to Fukushima soon.” Please understand that each person experienced a different set of circumstances that led them to leave Fukushima Prefecture. (Hisashi Iwata, 15)

Keywords

Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant accident and the people affected

A catastrophic tsunami hit the nuclear power plant in Fukushima Prefecture on March 11, 2011, causing an interruption to all sources of electricity. As a result, hydrogen explosions erupted in its reactor buildings, dispersing radioactive materials. This accident was rated a level 7 disaster, the same as the 1986 accident at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl in the former Soviet Union. The Fukushima accident has produced many difficult problems that will take a long time to resolve. Six years have passed since the accident, but around 80,000 people are still unable to return to their hometowns. There have also been cases in which children from Fukushima have been bullied at their new locations. The evacuation directive issued to residents of four municipalities around the power plant will be lifted this spring. But the recovery of these municipalities and people’s lives still have a long way to go. As of the end of February, about 660 people who left Fukushima have registered their residency in the Chugoku Region (Hiroshima and four other prefectures surrounding it). Since the Fukushima prefectural government will discontinue its housing assistance for voluntary evacuees this month, these people are facing a tough decision in terms of staying put or returning to northeastern Japan.

Junior writers’ impressions

When I was interviewing Natsuho Watanabe, I imagined how I would have felt if I had been in the same situation. An unprecedented disaster, moving to a new place in a hurry, separating from friends… I would have been so sad and at a loss what to do. I would have found it so hard to recover. Her softball club has brought new meaning to her life. Where can I find the meaning of my existence? She has overcome the hardships of the disaster and is now enjoying her life. Through this interview, I’ve come to think that I should become more practical and resolute. (Ishin Nakahara)

I had a chance to interview a student of the same age who endured the disaster of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Through this interview, I’ve come to realize the importance of disaster preparedness. I talked to my family about where to flee for safety in the event of an emergency. I hope our article will bring the student’s message about not forgetting this tragedy to many people, and people will take stronger action. (Nanaho Yamamoto)

This was the second time that I covered a topic related to the disaster caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake. I met Aya Miura of Asuchika again. According to Ms. Miura, there were many cases of gasoline or tires being stolen from cars and burglaries in the aftermath of the earthquake. This reminded me of some A-bomb survivors’ experiences I heard through interviews. After the atomic bombing, the survivors told me that there was a lot of theft. It’s scary that people can do such ugly things without considering others when their own daily lives are endangered. I want to be the kind of person who helps others, even in a situation like that. (Hisashi Iwata)

I used to lump together all the people who left their homes to live in different prefectures after the disaster. But through the interview I took part in, I’ve come to understand that each person has different feelings and a different way of life in their new home. I interviewed Issei Suzuki. He moved to Hiroshima not only because of the disaster, but because of other reasons, too. He told us that at first he was really afraid that people might show disdain toward him because he was from Fukushima. What really touched me were his words: “I want to help cheer up those who have evacuated from the disaster-hit area.” Around us are people who experienced the disaster or had a hard time even though they didn’t experience what happened directly. They have come to Hiroshima with different feelings. We need to be supportive and show that we’re open to living alongside them and helping one another. (Naruho Matsuzaki)

Before I was involved in this article, I hadn’t had an opportunity to listen to personal experiences about the earthquake, the tsunami, and the accident at the nuclear power plant. Through the interview I took part in, I realized how little I really knew about it. I was shocked to learn that people who evacuated from the disaster area have been going through such hard times. I think the most important thing is to understand their feelings. (Ai Mizoue)

Mio Niitsuma said, “The memories of the disaster are fading. I don’t want people to forget how ferocious natural disasters can be.” She hopes to work with children and tell them about her experience. She is also thinking about the idea of maintaining something tangible in Fukushima, like the A-bomb Dome, in order to convey memories of the disaster. I think that interviewing her and putting her thoughts into an article is one way to help realize her wish. (Kotoori Kawagishi)

When I asked Daisuke Sasajima where his hometown is, he responded, “Fukushima.” I’ve grown up in Hiroshima, and if I had to leave this city because of a disaster, I would respond the same way, that Hiroshima is my hometown. I realized that a person’s love for his or her hometown doesn’t change. The place where you grow up is an important place for you. This was my first interview on the theme of the disaster that hit northeastern Japan. If a disaster strikes my own area, I would follow his advice and deal with the situation as calmly as I could, without panicking. (Yui Morimoto)

Postscript

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Six years have now passed since the disaster that struck northeastern Japan. This is another sad anniversary. On March 11, 2011, I was at a reporters club at the Yamaguchi Prefectural Police Department, as I was stationed in that prefecture. I was waiting for an announcement about personnel changes, scheduled for three o’clock. I was sitting on a sofa and watching TV without really paying attention. The TV was showing deliberations on the budget bill at the Diet. Suddenly the image started shaking. “This is terrible,” I thought. Soon on-screen subtitles said that the hypocenter was off the coast of Sanriku, which is on the northeastern side of Honshu. I was shocked. If Tokyo is shaking like that, what could be happening in the Tohoku Region? The police department began to prepare to send support teams to the disaster area and things became hectic. We began interviewing people in the disaster area and those coming back from that part of the country.

On the night of the next day, I was able to talk to a student I knew well on the phone. She had fled to Sendai. She was confused because of a lack of information: “Did the nuclear power plant explode? What’s going to happen?” All I could say was, “Keep calm.” In retrospect, my heart aches as I recall that because it was an irresponsible remark. The international students at her school were evacuated to other prefectures in buses provided by the embassies of their nations. She must have been worried about what would happen to her as she felt like she was left behind.

For this article, we interviewed students who moved from Fukushima to Hiroshima after the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. They and their parents said that they didn’t know what to believe at that time. While I was taking notes, I remembered the pitiful crying I heard over the telephone that night. In a situation where you have no idea what information is correct and what action you should take, how should a journalist respond? These interviews gave me an opportunity to reflect on this. One high school student said that the media’s reporting made the facts invisible. I take this comment seriously.

This is our first article that covers the views of young people who experienced the disaster and evacuation. At first, I felt some apprehension because I thought that the interviews might be upsetting for them, but they were all determined to face this reality head on and they had the courage to put their experiences into words. Six years seems like a short time, but listening to them made me feel that it’s actually quite a long time, and above all, they have grown during the past six years. The junior writers also tried to take to heart the words of these young people, similar in age. The Tohoku Region is far from Hiroshima, but we have people in Hiroshima who experienced the disaster there. The junior writers have learned from them about the memories of the earthquake, the tsunami, and the nuclear accident, as well as their hardships and their resilience. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Aya Miura and Noriko Sasaki of Asuchika, a group of evacuees who are living in Hiroshima, and the young people and their parents who shared their experiences with us. Thanks to your kind cooperation, our junior writers were given a valuable opportunity to learn and grow.

What is Peace Seeds?

Peace Seeds are the seeds which can be spread around the world by thinking about peace and the preciousness of life from various viewpoints. To fill this world with flowering smiles, 30 junior writers, from the first year of junior high school to the third year of senior high school, choose themes, gather information, and write articles.

(Originally published on March 16, 2017)

Do you recall what happened on March 11, 2011? A massive earthquake, hitting the top of the seven-point Japanese scale of seismic intensity, triggered a monstrous tsunami. The tsunami slammed northeastern Japan and precipitated an accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. Six years after the triple disaster, some 123,000 people have still not been able to return home.

Some of those who left Fukushima Prefecture to live in Hiroshima are now teens. There are various reasons why they made this move from their hometowns, including the fear of radiation and the desire to attend a university in Hiroshima. While their hometowns are still in their thoughts, they are moving forward with their lives.

The junior writers of the Chugoku Shimbun interviewed several of these young people. They told us that, although they felt anxious at first, they found friends who offered them support while treating them the same as other friends.

Mio Niitsuma, 17, resident of Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima: New friends provide emotional support

Under a clear blue sky, a gathering was held on the bank of the river opposite the A-bomb Dome on March 11. They were there to pray for the victims of the disaster in 2011. Mio Niitsuma, 17, and her mother Noriko, 50, attended the gathering for the first time. Mio moved from Iwaki, Fukushima Prefecture to Hiroshima one year after the disaster. Now she is a second-year student at Koyohigashi Senior High School in Asakita Ward, Hiroshima. Though it is painful for her to recall what happened on that day, she has made up her mind to share her experience with others.

At the time, Mio was in fifth grade and in her classroom, preparing to return home, when the earthquake struck. The students huddled under their desks and waited for the tremors to subside. Her mother then arrived to pick her up and they went home. When she saw the television footage of the tsunami, she was stunned. She hadn’t known that the nuclear power plant, which would erupt in disaster the following day, was located about 45 kilometers from her home in the suburbs of Iwaki.

Afterward, her mother suggested that they move to Hiroshima so they wouldn’t have to worry about radiation. With support from her mother’s friends, they relocated to Hiroshima after Mio completed elementary school. She remembers feeling very lonely when her friends asked why she had to move so far away.

Still, she made new friends in Hiroshima, who helped her adjust. Mio says that she’s happy when chatting and laughing with her friends at school and that it was good she came to Hiroshima. She has decided to stay in Hiroshima in the future, too, but feels concern over the fact that people are starting to forget the nuclear disaster. She hopes that there will be no more nuclear accidents. She would like to work as a children’s nurse one day and tell them about her experience. (Nanaho Yamamoto, 17, and Kotoori Kawagishi, 14)

Daisuke Sasajima, 16, resident of Onomichi: Still wanting to go home

When his friends moved to other schools a year after the disaster, Daisuke Sasajima, now 16, was a fifth grader. At the time, Daisuke told them, “I won’t be leaving,” which meant, “I’ll always be here, so come back anytime.” But once he finished elementary school, he moved with his family to the city of Onomichi in Hiroshima Prefecture. Still, his love for his hometown of Koriyama, Fukushima has not dimmed.

Daisuke was at home when the earthquake occurred. Dishes, plates, and other things were scattered about in his house, and the water supply was shut off. The following day, he and his father went to a park and stood in line for five hours to get water. When they came home, his mother told them that there had been an explosion at the nuclear power plant. As he was unfamiliar with the subject of nuclear energy, he couldn’t comprehend what this meant.

School resumed in mid-April. To avoid being exposed to radiation, students had to wear long sleeves, long pants, and a mask, even in summer. A radiation meter was installed at the school. As a rising number of bags containing radioactive waste from decontamination work were piled on the school grounds, his friends moved away.

Daisuke has met supportive people in Onomichi. He is a first-year student at a high school in neighboring Okayama Prefecture. He has settled into his new life in Onomichi and its old townscape, and he enjoys playing with the cats in his neighborhood. “At the time, there was no choice but to leave Fukushima Prefecture. But part of me still wants to go back,” he said, expressing the mixed emotions he feels. (Ai Mizoue, 14, and Yui Morimoto, 13)

Natsuho Watanabe, 17, resident of Naka Ward, Hiroshima: Finding a sense of belonging

It was softball that helped Natsuho Watanabe, now 17, a sophomore at Hiroshima Jogakuin Senior High School, become more positive again. She left her home in Koriyama, Fukushima Prefecture two days after the disaster. It was a sad experience for her because she was unable to see her friends and say goodbye. She still cares about her friends from childhood, but she is now also committed to playing softball with her high school teammates and holds dreams for her future.

Natsuho was in fifth grade when the earthquake struck, and this experience made her feel very anxious. Water spilled out from her goldfish tank and she was so frightened, she couldn’t stop crying. She and her mother flew to Nagoya, where they heard the news about the accident at the nuclear power plant. Then they took a bullet train to her maternal grandparents’ home in Iwakuni, Yamaguchi Prefecture. After staying there for one year, they moved to Hiroshima when she entered junior high school.

Because she missed her friends so much, she vented her frustrations at her mother. There was a time, too, when she couldn’t bring herself to attend school. But the teacher in charge of the softball club, and the members of the team, invited her to join their practices. Then, in the autumn of her second year, she became one of the players in the starting lineup. She felt that the softball club was where she really belonged.

Now Natsuho is thinking about what she can do to help and she hopes to become a doctor. She wishes that her grandfather, who was a doctor, and her grandmother could witness her future. But they died in Koriyama after the nuclear accident. Smiling, she said, “Now I have twice as many friends as I once did, and good things have happened.” (Ishin Nakahara, 18)

Issei Suzuki, 20, resident of Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima: Encouraged by lives of Japanese immigrants to Hawaii

Issei Suzuki, 20, is a sophomore at the Hiroshima University of Economics, located in Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima. He and other students have been working on a project to promote exchanges between Japanese Hawaiians and young people in Hiroshima. He has been learning about the history of immigration and says, “I’ve been encouraged by those who lived courageous lives in a foreign country.” He moved from Nishiaizu, Fukushima Prefecture to Hiroshima two years ago.

He was not directly affected by the disaster that occurred when he was a second-year student in junior high school. But the situation there made the future of his mother’s job uncertain. So, in the autumn of his last year in junior high, his mother and his twin sister moved to Hiroshima, where his mother is originally from. Issei and his father remained behind in Fukushima. He tried to cherish every moment he could spend with his friends, since the disaster had taught him that there’s no telling what might happen in our lives.

But his father then died of illness. Issei moved to Hiroshima when he became a university student. In Hiroshima, though, he felt that some people didn’t have an accurate understanding of the effects of the nuclear accident. They hear about high radiation levels in one part of the Fukushima Prefecture and get the mistaken idea that the entire prefecture is contaminated. “Just because I’m from the disaster-hit area, people tend to feel pity for me,” he said. “But it’s better if people here give us their encouragement, like the way Hiroshima recovered from the atomic bombing.”

Aya Miura, head of Asuchika, a group of evacuees living in Hiroshima: Understand that each person’s circumstances are different

How should we treat the children who have moved from Fukushima Prefecture? The junior writers also interviewed Aya Miura, the head of Asuchika, a group for people who relocated to Hiroshima after the triple disaster that occurred in northeastern Japan. Below are some of her thoughts.

Children came here with their parents after the parents were forced to make the agonizing decision to move away from Fukushima Prefecture. Now that six years have passed since the disaster, the children have gotten used to their new lives in the Hiroshima area, with new friends and new schools, and they’re moving forward with their education. The advantage for children is that they can find a new circle of friends no matter their parents’ employment or their living environment.

But casual comments can be hurtful to them, such as “How long will you stay here?” or “When will you go back to Fukushima?” They may have misgivings, like “Maybe I shouldn’t stay here” or “Maybe I should go back to Fukushima soon.” Please understand that each person experienced a different set of circumstances that led them to leave Fukushima Prefecture. (Hisashi Iwata, 15)

Keywords

Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant accident and the people affected

A catastrophic tsunami hit the nuclear power plant in Fukushima Prefecture on March 11, 2011, causing an interruption to all sources of electricity. As a result, hydrogen explosions erupted in its reactor buildings, dispersing radioactive materials. This accident was rated a level 7 disaster, the same as the 1986 accident at the nuclear power plant in Chernobyl in the former Soviet Union. The Fukushima accident has produced many difficult problems that will take a long time to resolve. Six years have passed since the accident, but around 80,000 people are still unable to return to their hometowns. There have also been cases in which children from Fukushima have been bullied at their new locations. The evacuation directive issued to residents of four municipalities around the power plant will be lifted this spring. But the recovery of these municipalities and people’s lives still have a long way to go. As of the end of February, about 660 people who left Fukushima have registered their residency in the Chugoku Region (Hiroshima and four other prefectures surrounding it). Since the Fukushima prefectural government will discontinue its housing assistance for voluntary evacuees this month, these people are facing a tough decision in terms of staying put or returning to northeastern Japan.

Junior writers’ impressions

When I was interviewing Natsuho Watanabe, I imagined how I would have felt if I had been in the same situation. An unprecedented disaster, moving to a new place in a hurry, separating from friends… I would have been so sad and at a loss what to do. I would have found it so hard to recover. Her softball club has brought new meaning to her life. Where can I find the meaning of my existence? She has overcome the hardships of the disaster and is now enjoying her life. Through this interview, I’ve come to think that I should become more practical and resolute. (Ishin Nakahara)

I had a chance to interview a student of the same age who endured the disaster of the Great East Japan Earthquake. Through this interview, I’ve come to realize the importance of disaster preparedness. I talked to my family about where to flee for safety in the event of an emergency. I hope our article will bring the student’s message about not forgetting this tragedy to many people, and people will take stronger action. (Nanaho Yamamoto)

This was the second time that I covered a topic related to the disaster caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake. I met Aya Miura of Asuchika again. According to Ms. Miura, there were many cases of gasoline or tires being stolen from cars and burglaries in the aftermath of the earthquake. This reminded me of some A-bomb survivors’ experiences I heard through interviews. After the atomic bombing, the survivors told me that there was a lot of theft. It’s scary that people can do such ugly things without considering others when their own daily lives are endangered. I want to be the kind of person who helps others, even in a situation like that. (Hisashi Iwata)

I used to lump together all the people who left their homes to live in different prefectures after the disaster. But through the interview I took part in, I’ve come to understand that each person has different feelings and a different way of life in their new home. I interviewed Issei Suzuki. He moved to Hiroshima not only because of the disaster, but because of other reasons, too. He told us that at first he was really afraid that people might show disdain toward him because he was from Fukushima. What really touched me were his words: “I want to help cheer up those who have evacuated from the disaster-hit area.” Around us are people who experienced the disaster or had a hard time even though they didn’t experience what happened directly. They have come to Hiroshima with different feelings. We need to be supportive and show that we’re open to living alongside them and helping one another. (Naruho Matsuzaki)

Before I was involved in this article, I hadn’t had an opportunity to listen to personal experiences about the earthquake, the tsunami, and the accident at the nuclear power plant. Through the interview I took part in, I realized how little I really knew about it. I was shocked to learn that people who evacuated from the disaster area have been going through such hard times. I think the most important thing is to understand their feelings. (Ai Mizoue)

Mio Niitsuma said, “The memories of the disaster are fading. I don’t want people to forget how ferocious natural disasters can be.” She hopes to work with children and tell them about her experience. She is also thinking about the idea of maintaining something tangible in Fukushima, like the A-bomb Dome, in order to convey memories of the disaster. I think that interviewing her and putting her thoughts into an article is one way to help realize her wish. (Kotoori Kawagishi)

When I asked Daisuke Sasajima where his hometown is, he responded, “Fukushima.” I’ve grown up in Hiroshima, and if I had to leave this city because of a disaster, I would respond the same way, that Hiroshima is my hometown. I realized that a person’s love for his or her hometown doesn’t change. The place where you grow up is an important place for you. This was my first interview on the theme of the disaster that hit northeastern Japan. If a disaster strikes my own area, I would follow his advice and deal with the situation as calmly as I could, without panicking. (Yui Morimoto)

Postscript

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Six years have now passed since the disaster that struck northeastern Japan. This is another sad anniversary. On March 11, 2011, I was at a reporters club at the Yamaguchi Prefectural Police Department, as I was stationed in that prefecture. I was waiting for an announcement about personnel changes, scheduled for three o’clock. I was sitting on a sofa and watching TV without really paying attention. The TV was showing deliberations on the budget bill at the Diet. Suddenly the image started shaking. “This is terrible,” I thought. Soon on-screen subtitles said that the hypocenter was off the coast of Sanriku, which is on the northeastern side of Honshu. I was shocked. If Tokyo is shaking like that, what could be happening in the Tohoku Region? The police department began to prepare to send support teams to the disaster area and things became hectic. We began interviewing people in the disaster area and those coming back from that part of the country.

On the night of the next day, I was able to talk to a student I knew well on the phone. She had fled to Sendai. She was confused because of a lack of information: “Did the nuclear power plant explode? What’s going to happen?” All I could say was, “Keep calm.” In retrospect, my heart aches as I recall that because it was an irresponsible remark. The international students at her school were evacuated to other prefectures in buses provided by the embassies of their nations. She must have been worried about what would happen to her as she felt like she was left behind.

For this article, we interviewed students who moved from Fukushima to Hiroshima after the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant. They and their parents said that they didn’t know what to believe at that time. While I was taking notes, I remembered the pitiful crying I heard over the telephone that night. In a situation where you have no idea what information is correct and what action you should take, how should a journalist respond? These interviews gave me an opportunity to reflect on this. One high school student said that the media’s reporting made the facts invisible. I take this comment seriously.

This is our first article that covers the views of young people who experienced the disaster and evacuation. At first, I felt some apprehension because I thought that the interviews might be upsetting for them, but they were all determined to face this reality head on and they had the courage to put their experiences into words. Six years seems like a short time, but listening to them made me feel that it’s actually quite a long time, and above all, they have grown during the past six years. The junior writers also tried to take to heart the words of these young people, similar in age. The Tohoku Region is far from Hiroshima, but we have people in Hiroshima who experienced the disaster there. The junior writers have learned from them about the memories of the earthquake, the tsunami, and the nuclear accident, as well as their hardships and their resilience. I would like to express my sincere gratitude to Aya Miura and Noriko Sasaki of Asuchika, a group of evacuees who are living in Hiroshima, and the young people and their parents who shared their experiences with us. Thanks to your kind cooperation, our junior writers were given a valuable opportunity to learn and grow.

What is Peace Seeds?

Peace Seeds are the seeds which can be spread around the world by thinking about peace and the preciousness of life from various viewpoints. To fill this world with flowering smiles, 30 junior writers, from the first year of junior high school to the third year of senior high school, choose themes, gather information, and write articles.

(Originally published on March 16, 2017)