Survivors’ Stories: Megumi Shinoda, Naka Ward, Hiroshima

May 1, 2017

Able to live to talk about A-bombing and death of siblings

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Megumi Shinoda (née Sera), 85, a resident of Naka Ward, began talking about her experiences as an A-bomb survivor in April of this year. She lost her younger brother, Haruki, and her elder sister, Sachiyo, to the atomic bomb. Haruki was just two years old at the time and Sachiyo was 17. Her talk about her A-bomb experiences is part of a program provided by the City of Hiroshima.

In October 1945, a little over two months after the A-bomb attack, the body of Haruki, now reduced to skin and bone, was cremated on the dry riverbed near her house in Oshiba-cho (now part of Nishi Ward).

“There were no Buddhist sutras for his cremation, and in hindsight, I regret that so much,” Ms. Shinoda said. In those days, however, the cremation of her brother didn’t really register because cremations were a daily experience and, as a consequence, most people had become desensitized to them.

Back then, Ms. Shinoda was a second-year student at Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School (now Hiroshima Shoyo High School). On August 6, she was supposed to go to an area near the Tsurumi Bridge (now part of Naka Ward) with her classmates to help tear down houses and other buildings to create a fire lane. On that morning, however, she overslept and didn’t go, and instead ended up staying at home and folding origami paper with her brother.

Haruki was a cute child and had begun to speak quite a lot. But just at the moment Haruki said “Please eat” and offered some roasted beans to an elderly woman in the neighborhood who had come to borrow a grindstone, searing flames suddenly shot into the house.

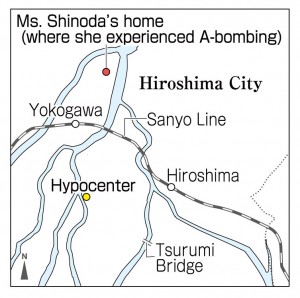

Ms. Shinoda’s home was located 2.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. The sliding paper doors flared up and the tatami mats burned and sagged down in the middle. An eerie silence lingered for some time. But then, hearing her mother’s voice call out “Megumi, Megumi,” Ms. Shinoda came back to herself. When she stood, she saw that the arms and legs of her mother and brother, who had both been in the narrow wooden passageway of their house, were red and swollen with some parts badly burned.

On that day, Ms. Shinoda’s elder sister, who had gone to work at the Sakan-cho branch of the Hiroshima Credit Union (now Hiroshima Shinkin Bank) in Takajo-machi (today’s Honkawa-cho in Naka Ward), located near the hypocenter, never returned home. On the following day, Ms. Shinoda walked around the city center with her father searching for her.

Near the Aioi Bridge, she came across large numbers of charred bodies scattered on the ground. She also saw the burnt carcasses of horses, their yellowish internal organs having erupted from their bodies by the force of the explosion. A boy, about the same age as her little brother, was sitting quietly beside the body of a woman who seemed to be his mother.

Suddenly, Ms. Shinoda heard a faint voice calling out “Is your name Sera?” The voice was coming from someone who had suffered severe burns from head to toe and was lying on a two-wheeled handcart. When she looked more closely, she realized that this person was actually a classmate. Records show that 262 students from Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School who were helping with the demolition near the Tsurumi Bridge were killed in the atomic bombing. Ms. Shinoda still wonders what happened to the classmate who spoke to her.

The hardships experienced by Ms. Shinoda’s family persisted after the war. Her little brother Haruki, who would cry out “Give back my sister!” whenever he saw an airplane flying overhead, suffered from severe diarrhea and eventually drew his last breath, in his mother’s arms, on October 22. Her father, who was working at the Army Clothing Depot, lost his job. Meanwhile, Ms. Shinoda developed a skin condition on her face, probably due to the aftereffects of her exposure to the atomic bomb, and had to leave Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School. She was two years behind when she entered Yasuda Girls’ High School.

With the encouragement of a teacher at school, she wrote her account of the atomic bombing for the book Children of the A-Bomb, which was compiled by Arata Osada. At the age of 22, she got married and went on to have three children. While busy raising her children, she gradually put distance between herself and her memories of the bombing.

Ms. Shinoda maintained a deep friendship with the late Suzuko Numata, her old high school teacher who spoke about her A-bomb experience for many years. Still, she was reluctant to talk about her own experience of the atomic bombing. In her mind, she felt she was unqualified to speak up because she hadn’t taken part in the demolition work on August 6.

A few years ago, she overcame pancreatic cancer and came to feel strongly that she had been able to live so she could hand down her A-bomb experience to younger generations. She now blames the war itself for the A-bomb attack and says that waging war is madness. She vows to continue talking about the preciousness of life, and searching for the remains of her missing sister, as long as her health holds up.

Teenagers’ impressions

War takes away everything

Ms. Shinoda’s two-year-old brother became emaciated and died two months after the atomic bombing. In those days, there was no food to eat except pumpkins, which had little taste. When her family tried to give him some pumpkin, he would cry and say, “I don’t want any more pumpkin!” I feel so sorry for her little brother. War takes away food, people’s possessions, houses, lives, and everything. I hope there will never be another war. (Jo Takeda, 10)

Innocent children became victims of war

Ms. Shinoda lost her elder sister and her house to the atomic bomb and she always felt hungry after the war. This is something I can’t imagine happening in our lives today. War causes suffering not only to soldiers on the battlefield but also to innocent children. In order to make sure that war will never happen again, I think we have to learn about the horrors of war and communicate them to future generations. (Haruna Oyama, 12)

Eager for us to understand the horrors of war

In her testimony, Ms. Shinoda explained how students were mobilized for the war effort in a way that was easy for us to understand. She did this because she’s eager to have younger generations understand the horrors of war. As I listened to her, and imagined the sorrow and grief she must have experienced over the death of her sister and brother and the devastated city that she saw after the atomic bombing, I reflected on the horror of nuclear weapons. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi, 15)

(Originally published on May 1, 2017)

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Megumi Shinoda (née Sera), 85, a resident of Naka Ward, began talking about her experiences as an A-bomb survivor in April of this year. She lost her younger brother, Haruki, and her elder sister, Sachiyo, to the atomic bomb. Haruki was just two years old at the time and Sachiyo was 17. Her talk about her A-bomb experiences is part of a program provided by the City of Hiroshima.

In October 1945, a little over two months after the A-bomb attack, the body of Haruki, now reduced to skin and bone, was cremated on the dry riverbed near her house in Oshiba-cho (now part of Nishi Ward).

“There were no Buddhist sutras for his cremation, and in hindsight, I regret that so much,” Ms. Shinoda said. In those days, however, the cremation of her brother didn’t really register because cremations were a daily experience and, as a consequence, most people had become desensitized to them.

Back then, Ms. Shinoda was a second-year student at Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School (now Hiroshima Shoyo High School). On August 6, she was supposed to go to an area near the Tsurumi Bridge (now part of Naka Ward) with her classmates to help tear down houses and other buildings to create a fire lane. On that morning, however, she overslept and didn’t go, and instead ended up staying at home and folding origami paper with her brother.

Haruki was a cute child and had begun to speak quite a lot. But just at the moment Haruki said “Please eat” and offered some roasted beans to an elderly woman in the neighborhood who had come to borrow a grindstone, searing flames suddenly shot into the house.

Ms. Shinoda’s home was located 2.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. The sliding paper doors flared up and the tatami mats burned and sagged down in the middle. An eerie silence lingered for some time. But then, hearing her mother’s voice call out “Megumi, Megumi,” Ms. Shinoda came back to herself. When she stood, she saw that the arms and legs of her mother and brother, who had both been in the narrow wooden passageway of their house, were red and swollen with some parts badly burned.

On that day, Ms. Shinoda’s elder sister, who had gone to work at the Sakan-cho branch of the Hiroshima Credit Union (now Hiroshima Shinkin Bank) in Takajo-machi (today’s Honkawa-cho in Naka Ward), located near the hypocenter, never returned home. On the following day, Ms. Shinoda walked around the city center with her father searching for her.

Near the Aioi Bridge, she came across large numbers of charred bodies scattered on the ground. She also saw the burnt carcasses of horses, their yellowish internal organs having erupted from their bodies by the force of the explosion. A boy, about the same age as her little brother, was sitting quietly beside the body of a woman who seemed to be his mother.

Suddenly, Ms. Shinoda heard a faint voice calling out “Is your name Sera?” The voice was coming from someone who had suffered severe burns from head to toe and was lying on a two-wheeled handcart. When she looked more closely, she realized that this person was actually a classmate. Records show that 262 students from Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School who were helping with the demolition near the Tsurumi Bridge were killed in the atomic bombing. Ms. Shinoda still wonders what happened to the classmate who spoke to her.

The hardships experienced by Ms. Shinoda’s family persisted after the war. Her little brother Haruki, who would cry out “Give back my sister!” whenever he saw an airplane flying overhead, suffered from severe diarrhea and eventually drew his last breath, in his mother’s arms, on October 22. Her father, who was working at the Army Clothing Depot, lost his job. Meanwhile, Ms. Shinoda developed a skin condition on her face, probably due to the aftereffects of her exposure to the atomic bomb, and had to leave Hiroshima Girls’ Commercial School. She was two years behind when she entered Yasuda Girls’ High School.

With the encouragement of a teacher at school, she wrote her account of the atomic bombing for the book Children of the A-Bomb, which was compiled by Arata Osada. At the age of 22, she got married and went on to have three children. While busy raising her children, she gradually put distance between herself and her memories of the bombing.

Ms. Shinoda maintained a deep friendship with the late Suzuko Numata, her old high school teacher who spoke about her A-bomb experience for many years. Still, she was reluctant to talk about her own experience of the atomic bombing. In her mind, she felt she was unqualified to speak up because she hadn’t taken part in the demolition work on August 6.

A few years ago, she overcame pancreatic cancer and came to feel strongly that she had been able to live so she could hand down her A-bomb experience to younger generations. She now blames the war itself for the A-bomb attack and says that waging war is madness. She vows to continue talking about the preciousness of life, and searching for the remains of her missing sister, as long as her health holds up.

Teenagers’ impressions

War takes away everything

Ms. Shinoda’s two-year-old brother became emaciated and died two months after the atomic bombing. In those days, there was no food to eat except pumpkins, which had little taste. When her family tried to give him some pumpkin, he would cry and say, “I don’t want any more pumpkin!” I feel so sorry for her little brother. War takes away food, people’s possessions, houses, lives, and everything. I hope there will never be another war. (Jo Takeda, 10)

Innocent children became victims of war

Ms. Shinoda lost her elder sister and her house to the atomic bomb and she always felt hungry after the war. This is something I can’t imagine happening in our lives today. War causes suffering not only to soldiers on the battlefield but also to innocent children. In order to make sure that war will never happen again, I think we have to learn about the horrors of war and communicate them to future generations. (Haruna Oyama, 12)

Eager for us to understand the horrors of war

In her testimony, Ms. Shinoda explained how students were mobilized for the war effort in a way that was easy for us to understand. She did this because she’s eager to have younger generations understand the horrors of war. As I listened to her, and imagined the sorrow and grief she must have experienced over the death of her sister and brother and the devastated city that she saw after the atomic bombing, I reflected on the horror of nuclear weapons. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi, 15)

(Originally published on May 1, 2017)