Survivors’ Stories: Yuji Egusa, 89, Fuchu, Hiroshima Prefecture

Mar. 20, 2017

Witnessing “hell” while moving through the ruined city

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Yuji Egusa, 89, a resident of Fuchu-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture who was a junior high school teacher, has talked to young people about the painful memories he experienced at the age of 17. He said, “The atomic bombing deprived people of their dignity of life in such a barbarous way. The bones of A-bomb victims still lie on the bottom of rivers that run through the city of Hiroshima. You should know that Hiroshima’s postwar reconstruction was built on the deaths of many, many people.”

Mr. Egusa, who was born in the city of Fukuyama, attended Hiroshima Normal School (now Hiroshima University’s Faculty of Education) and lived in a dormitory. He loved classical music and opera and wanted to become a music teacher.

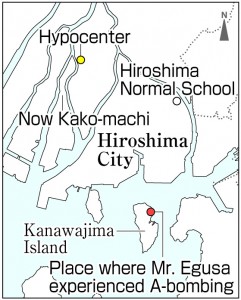

But in 1945, when he was a first-year student, no classes were held. Instead, students were mobilized for the war effort and Mr. Egusa was assigned to work at a military facility, the field shipping station on Kanawajima Island, off the coast of Ujina (now part of Minami Ward). There, he was told to help move ammunition and other things by ship, and a war song about ceaseless work was drummed into his head.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, too, Mr. Egusa was on the island. He was drinking tea in a break room when the left side of his face was hit by a wave of heat. He saw a flash of light and felt a powerful shock wave. He was about 6 kilometers from the hypocenter. He said, “When I went out, I saw a huge mushroom cloud. Ashes were falling, but at the time I knew nothing about the radiation.”

He was ordered to return to the school building in Shinonome-cho (now part of Minami Ward), and from there, groups of three people headed toward their teacher’s house, located in Funairi-machi (now part of Naka Ward) to help with relief efforts.

They moved through the city center, toward the west, and the conditions were like hell itself. Mr. Egusa said, “People were bent forward, and they struggled to continue walking. The eyeballs of some of them had popped from their sockets. The burnt scalp of others was dropping to their shoulders. These people were burned alive.”

Mr. Egusa drenched himself with water that was spewing from a broken pipe and headed on through the burning city. He said, “Near what’s now Kako-machi in Naka Ward, I thought I had come across a charred body, but the person stretched out a hand and pleaded for water. The hand nearly grabbed my leg, and I kicked at it. I wasn’t in my right mind.” He has no further memory of how he returned to the school.

Starting the next day, he was forced to help cremate the dead. “When I grabbed their wrists, the flesh slid off,” he said. “I tied ropes around the torsos and dragged the bodies.” With chopsticks and a can, he removed maggots that were festering in the wounds of survivors.

Mr. Egusa’s health also suffered. After returning to his parents’ home on August 16, the day that followed Japan’s defeat in the war, all of his hair fell out and he was unable to sit up.

Music became a ray of light at that dark time. About two weeks after he became bedridden, the radio began broadcasting classical music, which had been prohibited during the war. Listening to Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro,” he started to weep. He thought, “My life is tied to this music. I have to live.” Oddly enough, his condition gradually improved from the following day.

Mr. Egusa then practiced playing the piano relentlessly, as if seeking to make up for lost time during the war, then became a music teacher. He was also committed to making efforts for peace education so that Japan would not repeat the mistake of waging war. At the same time, he continued to be affected by his experience of the atomic bombing. He underwent operations on both eyes for A-bomb cataracts and his white blood cell count dropped to only half the normal number. When his eldest son, Koji, died 20 years ago at the age of 39, Mr. Egusa was distressed and wondered if his son’s death was connected to his own radiation exposure.

Six years ago, when the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant occurred, Mr. Egusa was shocked that Japan had not learned the hard lessons from the reality of the many damaging effects that followed the atomic bombings. Anxious over the possibility that nuclear weapons might again be used, he tells young people, “Not even one single nuclear weapon can be left on this earth.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

War deprived students of classes

Mr. Egusa, who wanted to become a music teacher, said, “It was heartbreaking that the music and art classes were the first to be canceled.” The things that were beautiful and developed the imagination and the subjects that were considered to be useless for the war effort were taken away. I’ll remember to appreciate how we’re able to have such classes at school because we’re now living in a peaceful time. (Kana Fukushima, 18)

Art motivated him to go on with his life

Mr. Egusa said, “Music has the power to rouse the spirit of people who are grieving.” Although he was weakened by his exposure to the A-bomb’s radiation, about ten days after the bombing, music motivated him to recover and it opened up a new path in his life. Music has also encouraged me and I’d like to live my life like Mr. Egusa, who relied on art for emotional support during a time of hardship. (Maiko Hanaoka, 18)

Conveying this reality to the next generation

Mr. Egusa experienced the atomic bombing at the age of 17, and the sights he still recalls, when he moved through the ruined city afterward, were so horrific. When he was on his way to help with the relief efforts, a person that looked like a charred body reached out and almost grabbed his leg. As I listened to his account, I wanted to cover my ears. But I think he wants young people to squarely face these facts and convey them to the next generation. (Shino Taniguchi, 18)

(Originally published on March 20, 2017)

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Yuji Egusa, 89, a resident of Fuchu-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture who was a junior high school teacher, has talked to young people about the painful memories he experienced at the age of 17. He said, “The atomic bombing deprived people of their dignity of life in such a barbarous way. The bones of A-bomb victims still lie on the bottom of rivers that run through the city of Hiroshima. You should know that Hiroshima’s postwar reconstruction was built on the deaths of many, many people.”

Mr. Egusa, who was born in the city of Fukuyama, attended Hiroshima Normal School (now Hiroshima University’s Faculty of Education) and lived in a dormitory. He loved classical music and opera and wanted to become a music teacher.

But in 1945, when he was a first-year student, no classes were held. Instead, students were mobilized for the war effort and Mr. Egusa was assigned to work at a military facility, the field shipping station on Kanawajima Island, off the coast of Ujina (now part of Minami Ward). There, he was told to help move ammunition and other things by ship, and a war song about ceaseless work was drummed into his head.

On the morning of August 6, 1945, too, Mr. Egusa was on the island. He was drinking tea in a break room when the left side of his face was hit by a wave of heat. He saw a flash of light and felt a powerful shock wave. He was about 6 kilometers from the hypocenter. He said, “When I went out, I saw a huge mushroom cloud. Ashes were falling, but at the time I knew nothing about the radiation.”

He was ordered to return to the school building in Shinonome-cho (now part of Minami Ward), and from there, groups of three people headed toward their teacher’s house, located in Funairi-machi (now part of Naka Ward) to help with relief efforts.

They moved through the city center, toward the west, and the conditions were like hell itself. Mr. Egusa said, “People were bent forward, and they struggled to continue walking. The eyeballs of some of them had popped from their sockets. The burnt scalp of others was dropping to their shoulders. These people were burned alive.”

Mr. Egusa drenched himself with water that was spewing from a broken pipe and headed on through the burning city. He said, “Near what’s now Kako-machi in Naka Ward, I thought I had come across a charred body, but the person stretched out a hand and pleaded for water. The hand nearly grabbed my leg, and I kicked at it. I wasn’t in my right mind.” He has no further memory of how he returned to the school.

Starting the next day, he was forced to help cremate the dead. “When I grabbed their wrists, the flesh slid off,” he said. “I tied ropes around the torsos and dragged the bodies.” With chopsticks and a can, he removed maggots that were festering in the wounds of survivors.

Mr. Egusa’s health also suffered. After returning to his parents’ home on August 16, the day that followed Japan’s defeat in the war, all of his hair fell out and he was unable to sit up.

Music became a ray of light at that dark time. About two weeks after he became bedridden, the radio began broadcasting classical music, which had been prohibited during the war. Listening to Mozart’s “The Marriage of Figaro,” he started to weep. He thought, “My life is tied to this music. I have to live.” Oddly enough, his condition gradually improved from the following day.

Mr. Egusa then practiced playing the piano relentlessly, as if seeking to make up for lost time during the war, then became a music teacher. He was also committed to making efforts for peace education so that Japan would not repeat the mistake of waging war. At the same time, he continued to be affected by his experience of the atomic bombing. He underwent operations on both eyes for A-bomb cataracts and his white blood cell count dropped to only half the normal number. When his eldest son, Koji, died 20 years ago at the age of 39, Mr. Egusa was distressed and wondered if his son’s death was connected to his own radiation exposure.

Six years ago, when the accident at the Fukushima No. 1 (Daiichi) nuclear power plant occurred, Mr. Egusa was shocked that Japan had not learned the hard lessons from the reality of the many damaging effects that followed the atomic bombings. Anxious over the possibility that nuclear weapons might again be used, he tells young people, “Not even one single nuclear weapon can be left on this earth.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

War deprived students of classes

Mr. Egusa, who wanted to become a music teacher, said, “It was heartbreaking that the music and art classes were the first to be canceled.” The things that were beautiful and developed the imagination and the subjects that were considered to be useless for the war effort were taken away. I’ll remember to appreciate how we’re able to have such classes at school because we’re now living in a peaceful time. (Kana Fukushima, 18)

Art motivated him to go on with his life

Mr. Egusa said, “Music has the power to rouse the spirit of people who are grieving.” Although he was weakened by his exposure to the A-bomb’s radiation, about ten days after the bombing, music motivated him to recover and it opened up a new path in his life. Music has also encouraged me and I’d like to live my life like Mr. Egusa, who relied on art for emotional support during a time of hardship. (Maiko Hanaoka, 18)

Conveying this reality to the next generation

Mr. Egusa experienced the atomic bombing at the age of 17, and the sights he still recalls, when he moved through the ruined city afterward, were so horrific. When he was on his way to help with the relief efforts, a person that looked like a charred body reached out and almost grabbed his leg. As I listened to his account, I wanted to cover my ears. But I think he wants young people to squarely face these facts and convey them to the next generation. (Shino Taniguchi, 18)

(Originally published on March 20, 2017)