Survivors’ Stories: Fumiko Kato, 87, Asaminami Ward, Hiroshima

Apr. 3, 2017

Remembering her classmates who were killed in the atomic bombing

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

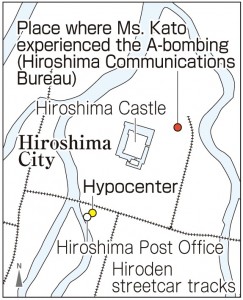

Fumiko Kato (née Kimoto), 87, who says that fate allowed her to survive the atomic bombing, has long thought of the classmates who lost their lives while working as mobilized students at other locations. Ms. Kato was 15 back then, a fourth-year student at Gion Girls’ High School, when she experienced the atomic bombing at a place about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. After the war, she gathered the A-bomb accounts of classmates who had managed to survive and has continued to share her experience of the bombing because she wants to help prevent the events of August 6, 1945 from fading into the past.

The day the city was attacked with the atomic bomb was a hot summer day and the sky was clear and blue. Ms. Kato left her home, located in Gion-cho (now part of Asaminami Ward), for Yokogawa Station on the Kabe Line. After getting off the train and walking for about 15 minutes, she reached the Hiroshima Communications Bureau located in Moto-machi (now part of Naka Ward), where she had been mobilized to work in the general affairs section a month earlier. As she was cooling herself with a paper fan at her work station on the fourth floor, the atomic bomb exploded.

The windows turned bright red and shattered into pieces. She was blown off her feet by the blast then blacked out. About 15 minutes later, she came to and found that she had been pinned under a heap of about 30 people who were working on that same floor. Blood dripped from those who had been hit by flying fragments of glass and her white blouse was stained a deep red. Frantic to flee, she managed to crawl out and exit the building.

Wanting to return home, and now in tears, she headed north with some classmates, in the opposite direction of the approaching flames. When she arrived home, her mother Fujino was alarmed to see her in the blood-covered blouse, but luckily, Ms. Kato had suffered no injuries. Her mother was overjoyed that she was safe.

People passed by on the road in front of their house, one after another, fleeing with their burnt skin peeling and dangling from their arms, which they held out before them. Trucks also continued moving past, with people piled up like baggage.

About 80 of her classmates in the fourth year were killed in the bombing. Some of them had been mobilized to work at the Hiroshima Post Office, located in Saiku-machi (now part of Naka Ward). After the war, the number of classes in her grade was reduced by half, from four to two. When a service was held to mourn the A-bomb victims, after she had graduated, a family member of one victim said, “Why did you survive?” These words pierced her heart.

None of them had been able to choose the place where they would be mobilized to work. But it crossed her mind that she should have died, too. Her father, Susume, was the principal of Gion Girls’ High School and he seemed to have endured difficult times as well. In 1982, just prior to his death, he said that he had been blamed by a student’s parents, who wanted to know why the principal’s daughter had been able to survive. With an aching heart, she and some friends erected a memorial monument at Oshimo Gakuen Gion Girls’ High School (now AICJ Junior & Senior High School, located in Asaminami Ward), which succeeded her school, in the year marking the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing. She also published a book of A-bomb accounts titled Ikasarete (Allowed to Live).

After marrying Yoshio Kato, who was also an A-bomb survivor, she became afraid of the effects of the exposure she had suffered to the A-bomb radiation. In 1959, she gave birth to a second son, but he died shortly after he was born, and her eldest daughter was found to be blind in one eye. She thought, “I may be fine, but my children could be suffering because of this radiation.”

To date, Ms. Kato has related her A-bomb account about 30 times. She said, “The war came about because of people’s arrogance. True peace won’t be realized unless nuclear weapons are abolished.” She was motivated to face her sad memories as a gesture of gratitude for the fact that she was able to survive the atomic bombing. On this occasion, she shared her account with a group of teens. To convey her message for the next generation, she created a tanka poem of 31 syllables: “I’ve grown old, yet I still share my story with young people and pray that my friends who were killed in the atomic bombing may rest in peace.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Want to convey the wish of the A-bomb survivors

I feel her wish to abolish nuclear weapons has now been handed down to me. Ms. Kato said that young people today need to learn more about what happened and share this with other people so that the tragedy of the atomic bombing won’t just become a page in a history book. The A-bomb survivors have never given up on their wish of nuclear abolition and this motivates me to convey their wish, and the preciousness of peace, to as many people as I can. (Kota Ueda, 13)

Fate spelled the difference between life and death

Ms. Kato’s classmates were killed in the atomic bombing. She said that if she had been assigned to work as a mobilized student at a place closer to the hypocenter, she might have died, too. It was pure luck where the students were assigned, but the location spelled the difference between life and death. I think Ms. Kato was very distressed by this fate. Nevertheless, she has shared her experience with others, and I felt her strong desire to hand down her memories. (Miyuu Okada, 16)

Atomic bombing brought hardship to survivors’ lives

Shedding tears, Ms. Kato said she was worried that, even though her own health was okay, her exposure to the bomb’s radiation had affected her children, and she felt bitter about that. Her experience conveys the horror of the atomic bombing. I saw how the atomic bomb not only had power when it was dropped but also has brought hardship to the survivors’ lives in the years that came after. (Marina Misaki, 17)

(Originally published on April 3, 2017)

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

Fumiko Kato (née Kimoto), 87, who says that fate allowed her to survive the atomic bombing, has long thought of the classmates who lost their lives while working as mobilized students at other locations. Ms. Kato was 15 back then, a fourth-year student at Gion Girls’ High School, when she experienced the atomic bombing at a place about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. After the war, she gathered the A-bomb accounts of classmates who had managed to survive and has continued to share her experience of the bombing because she wants to help prevent the events of August 6, 1945 from fading into the past.

The day the city was attacked with the atomic bomb was a hot summer day and the sky was clear and blue. Ms. Kato left her home, located in Gion-cho (now part of Asaminami Ward), for Yokogawa Station on the Kabe Line. After getting off the train and walking for about 15 minutes, she reached the Hiroshima Communications Bureau located in Moto-machi (now part of Naka Ward), where she had been mobilized to work in the general affairs section a month earlier. As she was cooling herself with a paper fan at her work station on the fourth floor, the atomic bomb exploded.

The windows turned bright red and shattered into pieces. She was blown off her feet by the blast then blacked out. About 15 minutes later, she came to and found that she had been pinned under a heap of about 30 people who were working on that same floor. Blood dripped from those who had been hit by flying fragments of glass and her white blouse was stained a deep red. Frantic to flee, she managed to crawl out and exit the building.

Wanting to return home, and now in tears, she headed north with some classmates, in the opposite direction of the approaching flames. When she arrived home, her mother Fujino was alarmed to see her in the blood-covered blouse, but luckily, Ms. Kato had suffered no injuries. Her mother was overjoyed that she was safe.

People passed by on the road in front of their house, one after another, fleeing with their burnt skin peeling and dangling from their arms, which they held out before them. Trucks also continued moving past, with people piled up like baggage.

About 80 of her classmates in the fourth year were killed in the bombing. Some of them had been mobilized to work at the Hiroshima Post Office, located in Saiku-machi (now part of Naka Ward). After the war, the number of classes in her grade was reduced by half, from four to two. When a service was held to mourn the A-bomb victims, after she had graduated, a family member of one victim said, “Why did you survive?” These words pierced her heart.

None of them had been able to choose the place where they would be mobilized to work. But it crossed her mind that she should have died, too. Her father, Susume, was the principal of Gion Girls’ High School and he seemed to have endured difficult times as well. In 1982, just prior to his death, he said that he had been blamed by a student’s parents, who wanted to know why the principal’s daughter had been able to survive. With an aching heart, she and some friends erected a memorial monument at Oshimo Gakuen Gion Girls’ High School (now AICJ Junior & Senior High School, located in Asaminami Ward), which succeeded her school, in the year marking the 40th anniversary of the atomic bombing. She also published a book of A-bomb accounts titled Ikasarete (Allowed to Live).

After marrying Yoshio Kato, who was also an A-bomb survivor, she became afraid of the effects of the exposure she had suffered to the A-bomb radiation. In 1959, she gave birth to a second son, but he died shortly after he was born, and her eldest daughter was found to be blind in one eye. She thought, “I may be fine, but my children could be suffering because of this radiation.”

To date, Ms. Kato has related her A-bomb account about 30 times. She said, “The war came about because of people’s arrogance. True peace won’t be realized unless nuclear weapons are abolished.” She was motivated to face her sad memories as a gesture of gratitude for the fact that she was able to survive the atomic bombing. On this occasion, she shared her account with a group of teens. To convey her message for the next generation, she created a tanka poem of 31 syllables: “I’ve grown old, yet I still share my story with young people and pray that my friends who were killed in the atomic bombing may rest in peace.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

Want to convey the wish of the A-bomb survivors

I feel her wish to abolish nuclear weapons has now been handed down to me. Ms. Kato said that young people today need to learn more about what happened and share this with other people so that the tragedy of the atomic bombing won’t just become a page in a history book. The A-bomb survivors have never given up on their wish of nuclear abolition and this motivates me to convey their wish, and the preciousness of peace, to as many people as I can. (Kota Ueda, 13)

Fate spelled the difference between life and death

Ms. Kato’s classmates were killed in the atomic bombing. She said that if she had been assigned to work as a mobilized student at a place closer to the hypocenter, she might have died, too. It was pure luck where the students were assigned, but the location spelled the difference between life and death. I think Ms. Kato was very distressed by this fate. Nevertheless, she has shared her experience with others, and I felt her strong desire to hand down her memories. (Miyuu Okada, 16)

Atomic bombing brought hardship to survivors’ lives

Shedding tears, Ms. Kato said she was worried that, even though her own health was okay, her exposure to the bomb’s radiation had affected her children, and she felt bitter about that. Her experience conveys the horror of the atomic bombing. I saw how the atomic bomb not only had power when it was dropped but also has brought hardship to the survivors’ lives in the years that came after. (Marina Misaki, 17)

(Originally published on April 3, 2017)