The Key to a World without Nuclear Weapons: The Power of Younger Generations, Part 5

Aug. 1, 2017

Third-generation survivor conveys grandfather’s experience of both atomic bombings

by Gosuke Nagahisa, Staff Writer

On July 7, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was adopted at the United Nations. But the nuclear weapon states and countries like Japan, which are under the nuclear umbrella, did not support the treaty. The road to nuclear abolition remains long and uphill, and it is vital that Hiroshima continue to convey its message to the world. Seventy-two years have passed since the atomic bombing, and the A-bomb survivors who have provided momentum for the adoption of the treaty are growing old. At the same time, younger generations have begun to hand down the sentiments of the survivors. The Chugoku Shimbun reports on how these younger generations are contributing to the cause of advancing a world without nuclear weapons.

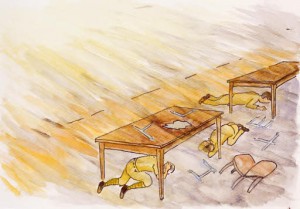

“It was like I was being chased by mushroom cloud” is a line from a story that describes the life of Tsutomu Yamaguchi, who experienced the atomic bombings of both Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The story is told with picture cards that illustrate the life of Mr. Yamaguchi, who died in 2010 at the age 93.

In mid-July, Kosuzu Harada, 42, Mr. Yamaguchi’s granddaughter, shared the story with some 100 students during a peace studies lesson at Nagasaki University. After reading out the lines attached to each picture, she concluded her presentation with her grandfather’s message: “There must never be a third atomic bombing. Please help abolish nuclear weapons.”

Seventy-two years ago, Mr. Yamaguchi was a design engineer for the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Nagasaki Shipyard. On August 6, he was in Hiroshima, on his way to the company’s Hiroshima shipyard. When the bomb exploded, he was about three kilometers from the hypocenter and he suffered burns and lost the hearing in his left ear. The next day, he was able to take the train back to Nagasaki, where he lived. Then, on August 9, the day after he arrived in Nagasaki, he was at work and telling about the terrible devastation in Hiroshima when the second atomic attack in human history took place. His workplace was three kilometers from the hypocenter of the second bomb.

Handing down her grandfather’s experience

At first, Mr. Yamaguchi did not talk about his experience in public. When he showed the desire to get involved in the antinuclear movement, his family members dissuaded him. This was a time when countries around the world were vying to expand their military might. “Because my father looked healthy at first glance, I was afraid these countries might think that it was okay to drop three or four atomic bombs,” said Toshiko Yamasaki, 69, Mr. Yamaguchi’s daughter and Ms. Harada’s mother.

But the turning point came in 2005. Mr. Yamaguchi’s second son, who was six months old at the time of the atomic bombing, died of cancer at the age of 59. Determined that no one else should face this same suffering, Mr. Yamaguchi began sharing his experience of the bombings in public. At that point, his family also gave him their support. When Mr. Yamaguchi developed stomach cancer, this didn’t stop him from visiting elementary schools and junior high schools, even when he was on an intravenous drip. He also traveled to the United States and made a speech during an event at the United Nations. His efforts to tell his story continued up to the age of 90.

Ms. Harada accompanied her grandfather on many occasions and watched him talk about his experience. When he spoke to young people, he said he wanted to “hand off the baton of life” to them, hoping that they would help hand down his account. In 2011, one year after his death, Ms. Harada began sharing her grandfather’s experience after receiving a request from Nagasaki University. She was given picture cards made by A-bomb survivors and started reading out the story describing her grandfather’s life to others. She registered to serve as a “family account teller” in a program launched by the City of Nagasaki in 2014, in which the children and grandchildren of A-bomb survivors hand down their experiences.

Picture story show in Hiroshima

“I hear people say that a third-generation survivor’s accounts carry less weight. But as I remained close to my grandfather, I can really speak out about his sufferings and emotional turmoil,” said Ms. Harada. Out of bitterness over the fact that his son died before him, Mr. Yamaguchi continued to relate his experience to others despite his illness and physical decline. Ms. Harada can share the anguish and desperation that only the members of his family know.

Last fiscal year, the City of Nagasaki began recruiting people who don’t have blood ties to survivors but wish to hand down A-bomb accounts, which is similar to Hiroshima’s “memory keeper” program. Now there are 17 such people in Nagasaki. As some survivors have no relatives to hand down their experiences, these programs seek to increase the number of people who can convey the survivors’ accounts.

Ms. Harada has been invited to an event in Hiroshima, on August 1, on the theme of third-generation A-bomb survivors. She plans to perform the picture story show at the event, the first time she will present the story in Hiroshima, where her grandfather experienced the first atomic bombing. “To fulfill my grandfather’s wish, I hope to create opportunities for younger generations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to come together,” said Ms. Harada. She is exploring what she can do as the granddaughter of a two-time survivor of the atomic bombings.

(Originally published on August 1, 2017)

by Gosuke Nagahisa, Staff Writer

On July 7, the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons was adopted at the United Nations. But the nuclear weapon states and countries like Japan, which are under the nuclear umbrella, did not support the treaty. The road to nuclear abolition remains long and uphill, and it is vital that Hiroshima continue to convey its message to the world. Seventy-two years have passed since the atomic bombing, and the A-bomb survivors who have provided momentum for the adoption of the treaty are growing old. At the same time, younger generations have begun to hand down the sentiments of the survivors. The Chugoku Shimbun reports on how these younger generations are contributing to the cause of advancing a world without nuclear weapons.

“It was like I was being chased by mushroom cloud” is a line from a story that describes the life of Tsutomu Yamaguchi, who experienced the atomic bombings of both Hiroshima and Nagasaki. The story is told with picture cards that illustrate the life of Mr. Yamaguchi, who died in 2010 at the age 93.

In mid-July, Kosuzu Harada, 42, Mr. Yamaguchi’s granddaughter, shared the story with some 100 students during a peace studies lesson at Nagasaki University. After reading out the lines attached to each picture, she concluded her presentation with her grandfather’s message: “There must never be a third atomic bombing. Please help abolish nuclear weapons.”

Seventy-two years ago, Mr. Yamaguchi was a design engineer for the Mitsubishi Heavy Industries Nagasaki Shipyard. On August 6, he was in Hiroshima, on his way to the company’s Hiroshima shipyard. When the bomb exploded, he was about three kilometers from the hypocenter and he suffered burns and lost the hearing in his left ear. The next day, he was able to take the train back to Nagasaki, where he lived. Then, on August 9, the day after he arrived in Nagasaki, he was at work and telling about the terrible devastation in Hiroshima when the second atomic attack in human history took place. His workplace was three kilometers from the hypocenter of the second bomb.

Handing down her grandfather’s experience

At first, Mr. Yamaguchi did not talk about his experience in public. When he showed the desire to get involved in the antinuclear movement, his family members dissuaded him. This was a time when countries around the world were vying to expand their military might. “Because my father looked healthy at first glance, I was afraid these countries might think that it was okay to drop three or four atomic bombs,” said Toshiko Yamasaki, 69, Mr. Yamaguchi’s daughter and Ms. Harada’s mother.

But the turning point came in 2005. Mr. Yamaguchi’s second son, who was six months old at the time of the atomic bombing, died of cancer at the age of 59. Determined that no one else should face this same suffering, Mr. Yamaguchi began sharing his experience of the bombings in public. At that point, his family also gave him their support. When Mr. Yamaguchi developed stomach cancer, this didn’t stop him from visiting elementary schools and junior high schools, even when he was on an intravenous drip. He also traveled to the United States and made a speech during an event at the United Nations. His efforts to tell his story continued up to the age of 90.

Ms. Harada accompanied her grandfather on many occasions and watched him talk about his experience. When he spoke to young people, he said he wanted to “hand off the baton of life” to them, hoping that they would help hand down his account. In 2011, one year after his death, Ms. Harada began sharing her grandfather’s experience after receiving a request from Nagasaki University. She was given picture cards made by A-bomb survivors and started reading out the story describing her grandfather’s life to others. She registered to serve as a “family account teller” in a program launched by the City of Nagasaki in 2014, in which the children and grandchildren of A-bomb survivors hand down their experiences.

Picture story show in Hiroshima

“I hear people say that a third-generation survivor’s accounts carry less weight. But as I remained close to my grandfather, I can really speak out about his sufferings and emotional turmoil,” said Ms. Harada. Out of bitterness over the fact that his son died before him, Mr. Yamaguchi continued to relate his experience to others despite his illness and physical decline. Ms. Harada can share the anguish and desperation that only the members of his family know.

Last fiscal year, the City of Nagasaki began recruiting people who don’t have blood ties to survivors but wish to hand down A-bomb accounts, which is similar to Hiroshima’s “memory keeper” program. Now there are 17 such people in Nagasaki. As some survivors have no relatives to hand down their experiences, these programs seek to increase the number of people who can convey the survivors’ accounts.

Ms. Harada has been invited to an event in Hiroshima, on August 1, on the theme of third-generation A-bomb survivors. She plans to perform the picture story show at the event, the first time she will present the story in Hiroshima, where her grandfather experienced the first atomic bombing. “To fulfill my grandfather’s wish, I hope to create opportunities for younger generations in Hiroshima and Nagasaki to come together,” said Ms. Harada. She is exploring what she can do as the granddaughter of a two-time survivor of the atomic bombings.

(Originally published on August 1, 2017)