Survivors’ Stories: Masahiro Maeda, Saeki Ward, Hiroshima

Jul. 3, 2017

Children use the arts to help father hand down A-bomb experience

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

The story of the A-bomb experience of Masahiro Maeda, 79, is included in Genbaku Taikenki (Experiences of the Atomic Bombing), a collection of accounts of the atomic bombing which the City of Hiroshima first invited residents to provide in 1950. The horrific scenes Mr. Maeda witnessed when he was only seven years old include the city in ruins and burnt to the ground with the survivors fleeing desperately from the fires. When Mr. Maeda became a father and tried to convey these memories to his children, they were frightened and they turned away, which frustrated him. Later on, though, his second son made use of animation and his first daughter created a comic book to help hand down his experience to younger generations.

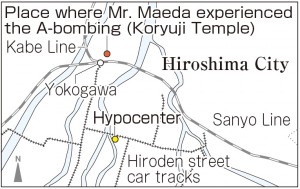

When Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb, Mr. Maeda was in second grade at Misasa National School (now Misasa Elementary School in Nishi Ward). When the Japanese military took over the school buildings for their own use, the students were forced to go to Koryuji Temple (located about 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter), not far from the school, to continue their studies. On the morning of August 6, 1945, he was playing with classmates in the southern part of the temple grounds.

At the sound of an airplane, Mr. Maeda looked up and saw three shiny objects in the sky. Then he heard a woman’s angry voice say, “What are you doing?” and turned to look at her. A classmate had thrown a rock at a lizard scurrying along a fence, but instead of hitting the creature, he had broken the window of her neighbor’s house.

He looked down and there was a sudden flash of blinding light. He found himself enveloped by this tremendous flash. “Am I dead?” he wondered to himself. When he opened his eyes, he saw power lines hanging down and found that he had been blown about 10 meters away. The woman who had been scolding the children was now calling them together in the shade near the fire cistern. Her hair was standing on end.

Prompted to board a truck by civil defense volunteers, Mr. Maeda eventually reached the Shinjo Bridge on foot. In the meantime, fire was rising on the opposite side of the river so he entered the water and crossed to the other side. As he was fleeing, he saw his brother Yoshitaka, a fourth grader at Sotoku Junior High School who was working that day as a mobilized student. Mr. Maeda called out his name, but his brother didn’t recognize him because Mr. Maeda’s head had been scorched by the blast and, as a result, his face had become swollen. That night, he stayed at someone’s home near Furuichi-cho (now part of Asaminami Ward).

The next day, Mr. Maeda was reunited with his parents, his younger sister, and his grandmother. Later, it was learned that his older sister Miyoko, who was a student at Shintoku Girls’ High School and was helping to create a fire lane near the Tsurumi Bridge when the bomb exploded, perished in the attack. After the bombing, Mr. Maeda’s family stayed with relatives, but from the fall, they began living in a makeshift hut. Although his burns healed, he was left with keloid scars.

Mr. Maeda attended Sotoku Junior and Senior High School and became a member of the art club. In response to a request from an American foundation, he drew a picture on the theme of world peace with the hope that a wonderful war-free future was on the horizon. With great excitement, he submitted his drawing, which showed the earth surrounded by the flags of the world’s nations. He submitted other pictures, too, and won awards for his artwork for five consecutive years. These experiences led him to become a designer.

Mr. Maeda got married at the age of 25 and had three children. Each year, as August 6 approached, he would tell his children about his experience of the war and the horror of the atomic bomb. His stories, though, came to frighten them. He then thought of making an animated film to preserve his account and, using 8mm film, recorded the roads he walked along to escape from the city center on the day of the bombing. But this film idea was not fulfilled.

Eventually, though, that project was taken over and realized by his second son, Minoru Maeda, 46. With the cooperation of his family, Minoru created a 19-minute animated film over the course of 10 years, completing it in 2002. The film focused on heartwarming scenes of the daily lives of children before the atomic bomb decimated the city, but the bombing itself, which ultimately upended the children’s lives, was given little screen time.

Minoru sought to depict his father’s experience as a child so that even small children could personally relate to the great tragedy caused by the atomic bombing. But, at first, his father was dissatisfied with the film because it had underplayed the awful destruction.

However, when the film was screened, Mr. Maeda was surprised by the response of the audience, who said they were eager for an even longer film. “We were delighted by their response,” he said, “and felt this positive feedback was much more important than the feedback from people who said they didn’t want to hear about the atomic bombing anymore.” After that, Naoko Maeda, 44, Mr. Maeda’s first daughter and an illustrator, created a comic book of more than 500 pages which relates the story of her father and brother creating the animated film.

Mr. Maeda believes that these works of art made by his children can help people imagine the horror of the atomic bomb, even if just a little. Holding the vivid memories of his younger days in mind, he hopes there will be no more war and loss of loved ones.

Teenagers’ impressions

Contributing to peace in our own way

Mr. Maeda has tried to convey the importance of peace to his children through his testimony, an animated film, and a comic book. Although he used different ways to communicate his experience, and his message has been heard differently by each child, he seems really happy that his children understand his feelings. Through Mr. Maeda, I learned that it’s okay for me to be involved in peacebuilding efforts in my own way. From now on, after my interviews with A-bomb survivors, I’m going to write down their stories in my notebook and summarize them for newspaper articles as faithfully as I can. (Akane Sato, 14)

Memories convey shock of the atomic bombing

Mr. Maeda told us that he’s unable to forget the sight of downed power lines in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. In my case, I have no clear memories of things I saw as a second grader, like Mr. Maeda when he was that age at the time of the bombing. I understand clearly how shocked those small children must have been when Hiroshima was attacked. In order to convey the message, to the generations that follow, that the atomic bombing must never be forgotten, I now realize the importance of continuing to share the survivors’ stories with my family and friends. (Miyuu Okada, 16)

(Originally published on July 3, 2017)

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

The story of the A-bomb experience of Masahiro Maeda, 79, is included in Genbaku Taikenki (Experiences of the Atomic Bombing), a collection of accounts of the atomic bombing which the City of Hiroshima first invited residents to provide in 1950. The horrific scenes Mr. Maeda witnessed when he was only seven years old include the city in ruins and burnt to the ground with the survivors fleeing desperately from the fires. When Mr. Maeda became a father and tried to convey these memories to his children, they were frightened and they turned away, which frustrated him. Later on, though, his second son made use of animation and his first daughter created a comic book to help hand down his experience to younger generations.

When Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb, Mr. Maeda was in second grade at Misasa National School (now Misasa Elementary School in Nishi Ward). When the Japanese military took over the school buildings for their own use, the students were forced to go to Koryuji Temple (located about 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter), not far from the school, to continue their studies. On the morning of August 6, 1945, he was playing with classmates in the southern part of the temple grounds.

At the sound of an airplane, Mr. Maeda looked up and saw three shiny objects in the sky. Then he heard a woman’s angry voice say, “What are you doing?” and turned to look at her. A classmate had thrown a rock at a lizard scurrying along a fence, but instead of hitting the creature, he had broken the window of her neighbor’s house.

He looked down and there was a sudden flash of blinding light. He found himself enveloped by this tremendous flash. “Am I dead?” he wondered to himself. When he opened his eyes, he saw power lines hanging down and found that he had been blown about 10 meters away. The woman who had been scolding the children was now calling them together in the shade near the fire cistern. Her hair was standing on end.

Prompted to board a truck by civil defense volunteers, Mr. Maeda eventually reached the Shinjo Bridge on foot. In the meantime, fire was rising on the opposite side of the river so he entered the water and crossed to the other side. As he was fleeing, he saw his brother Yoshitaka, a fourth grader at Sotoku Junior High School who was working that day as a mobilized student. Mr. Maeda called out his name, but his brother didn’t recognize him because Mr. Maeda’s head had been scorched by the blast and, as a result, his face had become swollen. That night, he stayed at someone’s home near Furuichi-cho (now part of Asaminami Ward).

The next day, Mr. Maeda was reunited with his parents, his younger sister, and his grandmother. Later, it was learned that his older sister Miyoko, who was a student at Shintoku Girls’ High School and was helping to create a fire lane near the Tsurumi Bridge when the bomb exploded, perished in the attack. After the bombing, Mr. Maeda’s family stayed with relatives, but from the fall, they began living in a makeshift hut. Although his burns healed, he was left with keloid scars.

Mr. Maeda attended Sotoku Junior and Senior High School and became a member of the art club. In response to a request from an American foundation, he drew a picture on the theme of world peace with the hope that a wonderful war-free future was on the horizon. With great excitement, he submitted his drawing, which showed the earth surrounded by the flags of the world’s nations. He submitted other pictures, too, and won awards for his artwork for five consecutive years. These experiences led him to become a designer.

Mr. Maeda got married at the age of 25 and had three children. Each year, as August 6 approached, he would tell his children about his experience of the war and the horror of the atomic bomb. His stories, though, came to frighten them. He then thought of making an animated film to preserve his account and, using 8mm film, recorded the roads he walked along to escape from the city center on the day of the bombing. But this film idea was not fulfilled.

Eventually, though, that project was taken over and realized by his second son, Minoru Maeda, 46. With the cooperation of his family, Minoru created a 19-minute animated film over the course of 10 years, completing it in 2002. The film focused on heartwarming scenes of the daily lives of children before the atomic bomb decimated the city, but the bombing itself, which ultimately upended the children’s lives, was given little screen time.

Minoru sought to depict his father’s experience as a child so that even small children could personally relate to the great tragedy caused by the atomic bombing. But, at first, his father was dissatisfied with the film because it had underplayed the awful destruction.

However, when the film was screened, Mr. Maeda was surprised by the response of the audience, who said they were eager for an even longer film. “We were delighted by their response,” he said, “and felt this positive feedback was much more important than the feedback from people who said they didn’t want to hear about the atomic bombing anymore.” After that, Naoko Maeda, 44, Mr. Maeda’s first daughter and an illustrator, created a comic book of more than 500 pages which relates the story of her father and brother creating the animated film.

Mr. Maeda believes that these works of art made by his children can help people imagine the horror of the atomic bomb, even if just a little. Holding the vivid memories of his younger days in mind, he hopes there will be no more war and loss of loved ones.

Teenagers’ impressions

Contributing to peace in our own way

Mr. Maeda has tried to convey the importance of peace to his children through his testimony, an animated film, and a comic book. Although he used different ways to communicate his experience, and his message has been heard differently by each child, he seems really happy that his children understand his feelings. Through Mr. Maeda, I learned that it’s okay for me to be involved in peacebuilding efforts in my own way. From now on, after my interviews with A-bomb survivors, I’m going to write down their stories in my notebook and summarize them for newspaper articles as faithfully as I can. (Akane Sato, 14)

Memories convey shock of the atomic bombing

Mr. Maeda told us that he’s unable to forget the sight of downed power lines in the aftermath of the atomic bombing. In my case, I have no clear memories of things I saw as a second grader, like Mr. Maeda when he was that age at the time of the bombing. I understand clearly how shocked those small children must have been when Hiroshima was attacked. In order to convey the message, to the generations that follow, that the atomic bombing must never be forgotten, I now realize the importance of continuing to share the survivors’ stories with my family and friends. (Miyuu Okada, 16)

(Originally published on July 3, 2017)