Peace Seeds: Teens in Hiroshima Sow Seeds of Peace (Part 46)

Jul. 20, 2017

Suicide attack unit engaged in rescue efforts after A-bombing of Hiroshima

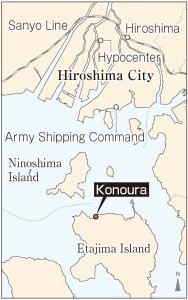

During World War II, there was a military unit that underwent training on Etajima Island in the Seto Inland Sea, then headed to Hiroshima to help with rescue efforts after the city was attacked with the atomic bomb. This unit was known as the 10th educational unit of the Army’s Marine Training Division, but it was, in fact, the marine suicide attack unit. The unit was formed to carry out suicide attacks by sinking enemy ships that sought to access mainland Japan. Their attack craft, mounted with bombs, were intended to crash into these ships and explode.

However, the atomic bombing changed the fate of the unit’s members who had committed to sacrificing their lives for their country. Their training was suspended and they instead hurried into the city center in the wake of the A-bomb attack to help rescue the wounded and remove the dead. Then, when the war ended, their lives were saved, but the miserable scenes that these men saw in the ruins of the A-bombed city have remained seared into their memories.

A memorial to the soldiers of this unit stands at Konoura, at the northern end of Etajima Island, where the unit was based. The memorial was raised in 1967 on the shore opposite Hiroshima, across the beautiful sea, and is engraved with the sad fact that 1,636 men, out of a total of 2,288 soldiers in the unit, were killed in their attacks. Some members who took part in the rescue efforts in Hiroshima suffered from the effects of their radiation exposure after the war.

The junior writers interviewed a survivor who experienced the double hardships of the suicide attack training and the rescue efforts in the aftermath of the atomic bombing.

Isao Wada, former member of the marine suicide attack unit

Isao Wada, 91, who once had a barber shop in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, was a member of the army’s marine suicide attack unit. When he was being trained, he was proud of his role because he thought that dying from an attack like this would be more manly than being hit by a bullet. But after the atomic bombing, he witnessed horrific scenes in the city center. As he grew older, he began to open up about his experience. “War means killing on both sides,” he said. “We should never engage in another war.”

In February 1945, Mr. Wada joined the suicide attack unit after enlisting in the army. Along with other young people from across Japan, he received basic training in such skills as using a gun and operating a ship at Shodoshima Island in Kagawa Prefecture. Then, in July of that year, he moved to the base at Konoura, on Etajima Island, and began training with the suicide attack unit. He practiced manning a plywood craft and simulating a bomb attack against an enemy ship that was actually a Japanese vessel that had stalled in the open sea after running out of fuel.

Large waves easily overturned his craft and the parts soaked in seawater began to decay. Looking back, he said, “The craft was easily damaged unless we walked on the frame, so we had to take good care of it.” Most of the trainees in the unit, numbering about 1,000 in the barracks, were youth under the age of 20. Some of the young trainees sobbed at night because of the harsh training they faced each day.

On August 6, Mr. Wada, who was then 19 years old, was resting in his barracks after breakfast. Suddenly, there was a great boom and he felt the building shake. When he rushed outside, he saw a mushroom cloud growing in the sky above Hiroshima and smoke from fire rising up from the ground.

The training scheduled for that day was cancelled. Instead, the members of the unit were sent by ship from Etajima Island to Hiroshima to help with rescue efforts. Mr. Wada arrived at Ujina Port and headed to the city center around 2 p.m. He then went on foot in the direction of the head office of the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company (in today’s Naka Ward), which became the temporary base for their rescue operations.

Because the houses on both sides of the street were in flames, he was forced to walk down the center of the road to avoid the sparks. He felt stunned when he stood on the Miyukibashi Bridge and could see the distant Koi area because the bombing had wiped away the buildings in the city center. He and other members of his unit fashioned makeshift stretchers using straw mats and poles, and carried the wounded. That night, he lay down beside the road, but he was in such shock, he said, that he was unable to sleep.

The next day, August 7, he transported the bodies of victims by truck, and on August 8, helped cremate them near the Motoyasu River. The bodies were piled up high, with layers of logs in between, then set on fire. He couldn’t imagine what sort of bomb had caused such tragedy. He also came across many people who begged him for water. Mr. Wada said that he gave them some, thinking they would die shortly anyway.

He continued helping with these relief efforts until August 12, then returned to Etajima Island. Some members of his unit suffered from hair loss or bleeding gums as a result of their exposure to the bomb’s radiation. Mr. Wada’s reaction was more mild, and he endured only diarrhea for a week. Because the war ended before he was assigned to carry out a suicide attack, he admitted that he felt relieved. Still, he had mixed feelings. “If the war had lasted six more months, I would have died, too,” he said.

Mr. Wada said that he hopes young people today can appreciate how priceless it is to have the opportunity to live free and enjoyable lives. As he reflected on the many deaths he witnessed in the burnt ruins of the city, he said firmly, in this 72nd year since the atomic bombing, “Nuclear weapons can only lead to the destruction of human beings.” (Naruho Matsuzaki, 16, Tokitsuna Kawagishi, 16, and Miki Meguro, 16)

Go Okumoto, researcher of local battle sites

The army’s marine suicide attack unit was formed in 1944, when the tide of the war was turning against Japan. Gou Okumoto, 45, a resident of Etajima City and the captain of a ferry who researches local battle sites, told us that the unit forged into the fighting without proper equipment.

Special marine officer candidates, most of them in their late teens who had applied to participate, were assigned to the unit and trained with a special craft nicknamed “Maru-re.” The role of the unit involved attacking enemy ships that ventured into Japanese waters, not actively pursuing them. There were 53 squadrons, and each was comprised of 100 soldiers. After the members of the unit were trained on Shodoshima Island or Etajima Island, they were dispatched to the Philippines, which was part of the Japanese territories at the time, as well as Okinawa and parts of Kyushu.

The soldiers would board their crafts at night to carry out their missions. They approached the enemy ship, dropped a bomb called a depth charge, then retreated quickly because the weapon would explode in seven seconds. The aim of the attack was to blast a hole in the body of the enemy ship or damage its framework so that it would sink. However, because the “Maru-re” craft was not equipped with a gun or roof for defense, it was very vulnerable to machine-gun fire. It was also a difficult craft to operate. Under these circumstances, the unit finally turned into a suicide attack squad in which the soldiers conducted suicide attacks by crashing into the enemy ships with their boats.

The design of the “Maru-re” craft was simple so that it could be easily mass produced. The body was 5.6 meters long and 1.8 meters wide, and was made of a Japanese Zelkova frame covered only with waterproof plywood that was four to six millimeters thick. Because the craft was powered by an automobile engine, it was vulnerable to water and stalled frequently. The 250-kilogram depth charge, which was placed at the rear of the craft, was affixed only with wire.

Mr. Okumoto has turned his research on the suicide attack unit into a book. He said, “The lives of those who were killed, as well as the unit’s rescue efforts after the atomic bombing, have not been widely recognized. I would like many more people to be aware of this history.” (Honoka Hiramatsu, 14)

Satoru Ubuki, expert on the history of the A-bombing

To help with relief efforts in Hiroshima in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, the Akatsuki unit, which operated under the Army Shipping Command in Ujina, was dispatched to the disaster zone. The army’s marine suicide attack unit was part of the Akatsuki unit. What impact did the rescue activities by the military have? The junior writers interviewed Satoru Akira, 70, a resident of Kure, who is an expert on the history of the atomic bombing and Hiroshima’s post-war period.

The fact that the army took part in relief efforts after the Hiroshima bombing was unique compared to other places. Removing and cremating the dead was an important task for the army, as much as aiding the wounded, because it wanted to avoid unsanitary conditions and the loss of fighting spirit among the general public. According to Record of the A-bomb Disaster, roughly 36% of the total number of bodies were removed and cremated by the army within two weeks of the atomic bombing.

Because the unit stationed near Hiroshima Castle was decimated, the Akatsuki unit played a significant role in the relief efforts, as they were stationed in the adjacent area and suffered less damage in the A-bomb attack. After their rescue operations ended, the members of the unit who had been brought together from across Japan returned to their hometowns. Though they faced difficulties finding witnesses when they later applied for the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate, a veterans’ association, which formed branches in many parts of Japan, assisted them with this need.

Many members of the the army’s marine suicide attack unit experienced the atomic bombing while in their late teens. Some suffered the effects of their exposure to the bomb’s radiation, such as a decrease in their white blood count. Mr. Ubuki said, “The youngsters who had already prepared themselves to serve as humans bombs and die in a suicide attack saved the lives of others. We should not forget this fact.” He added, “Japanese society of that time must be blamed, too, because it forced them into a situation, at a young age, where their health suffered as a result of their radiation exposure.” (Riho Kito, 16)

Junior writers’ impressions

Through the interview for this article, I learned about the army’s marine suicide attack unit, which Mr. Wada belonged to, for the first time. It was distressing for me to hear how young people like us were forced to endure harsh training and that many of them lost their lives when they crashed their small, fragile crafts into enemy ships. Also, when Mr. Wada told us that he had believed that dying in a suicide attack demonstrated a man’s true worth, my heart ached as I thought about how the young people of that time had to live amid conditions where they felt compelled to fight and sacrifice themselves for their country. (Naruho Matsuzaki)

This was the first time I took part in a telephone interview, but it was a bit difficult because I couldn’t see the person’s face directly. Still, I was impressed by the comments that were made by Mr. Ubuki, the person I interviwed. He told me, “It would be easier for you to understand this by relating the damages of the atomic bombing to current issues.” I want to continue working hard in my reporting. (Riho Kito)

I went to Etajima Island in person and interviewed Mr. Wada. The memories that he shared with me of August 6, the day Hiroshima was attacked, were beyond what I had imagined. When we climbed the mountain and I listened to his A-bomb experience, I felt as if I could see the big mushroom cloud with my own eyes as I looked out over the sea toward Hiroshima. I want to do my best to convey the A-bomb experiences of survivors like Mr. Wada to younger generations so that the world can continue to be a peaceful place. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi)

Mr. Wada said, “The atmosphere of that time made us think that dying from a suicide attack, without any hesitation, was just a matter of course.” This is hard for me to imagine, since I live in today’s Japan, which is not at war, but I think it’s horrible that so many people didn’t doubt such ideas at that time. So that an era like that won’t ever occur again, I really felt how important it is that we raise our voices and demand that war must never be repeated. (Miki Meguro)

I interviewed Mr. Okumoto. Though, before that, I didn’t know anything about the army’s marine suicide attack unit, I understood how hopeless the war was after I heard about the suicide attack unit and its flimsy “Maru-re” craft. I felt strongly that we have to shine more light on the many hidden aspects of history and reflect on the damage wrought by the atomic bombing more thoroughly. (Honoka Hiramatsu)

What is Peace Seeds?

Peace Seeds are the seeds which can be spread around the world by thinking about peace and the preciousness of life from various viewpoints. To fill this world with flowering smiles, 27 junior writers, from the first year of junior high school to the third year of senior high school, choose themes, gather information, and write articles.

(Originally published on July 20, 2017)

During World War II, there was a military unit that underwent training on Etajima Island in the Seto Inland Sea, then headed to Hiroshima to help with rescue efforts after the city was attacked with the atomic bomb. This unit was known as the 10th educational unit of the Army’s Marine Training Division, but it was, in fact, the marine suicide attack unit. The unit was formed to carry out suicide attacks by sinking enemy ships that sought to access mainland Japan. Their attack craft, mounted with bombs, were intended to crash into these ships and explode.

However, the atomic bombing changed the fate of the unit’s members who had committed to sacrificing their lives for their country. Their training was suspended and they instead hurried into the city center in the wake of the A-bomb attack to help rescue the wounded and remove the dead. Then, when the war ended, their lives were saved, but the miserable scenes that these men saw in the ruins of the A-bombed city have remained seared into their memories.

A memorial to the soldiers of this unit stands at Konoura, at the northern end of Etajima Island, where the unit was based. The memorial was raised in 1967 on the shore opposite Hiroshima, across the beautiful sea, and is engraved with the sad fact that 1,636 men, out of a total of 2,288 soldiers in the unit, were killed in their attacks. Some members who took part in the rescue efforts in Hiroshima suffered from the effects of their radiation exposure after the war.

The junior writers interviewed a survivor who experienced the double hardships of the suicide attack training and the rescue efforts in the aftermath of the atomic bombing.

Isao Wada, former member of the marine suicide attack unit

Isao Wada, 91, who once had a barber shop in Naka Ward, Hiroshima, was a member of the army’s marine suicide attack unit. When he was being trained, he was proud of his role because he thought that dying from an attack like this would be more manly than being hit by a bullet. But after the atomic bombing, he witnessed horrific scenes in the city center. As he grew older, he began to open up about his experience. “War means killing on both sides,” he said. “We should never engage in another war.”

In February 1945, Mr. Wada joined the suicide attack unit after enlisting in the army. Along with other young people from across Japan, he received basic training in such skills as using a gun and operating a ship at Shodoshima Island in Kagawa Prefecture. Then, in July of that year, he moved to the base at Konoura, on Etajima Island, and began training with the suicide attack unit. He practiced manning a plywood craft and simulating a bomb attack against an enemy ship that was actually a Japanese vessel that had stalled in the open sea after running out of fuel.

Large waves easily overturned his craft and the parts soaked in seawater began to decay. Looking back, he said, “The craft was easily damaged unless we walked on the frame, so we had to take good care of it.” Most of the trainees in the unit, numbering about 1,000 in the barracks, were youth under the age of 20. Some of the young trainees sobbed at night because of the harsh training they faced each day.

On August 6, Mr. Wada, who was then 19 years old, was resting in his barracks after breakfast. Suddenly, there was a great boom and he felt the building shake. When he rushed outside, he saw a mushroom cloud growing in the sky above Hiroshima and smoke from fire rising up from the ground.

The training scheduled for that day was cancelled. Instead, the members of the unit were sent by ship from Etajima Island to Hiroshima to help with rescue efforts. Mr. Wada arrived at Ujina Port and headed to the city center around 2 p.m. He then went on foot in the direction of the head office of the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company (in today’s Naka Ward), which became the temporary base for their rescue operations.

Because the houses on both sides of the street were in flames, he was forced to walk down the center of the road to avoid the sparks. He felt stunned when he stood on the Miyukibashi Bridge and could see the distant Koi area because the bombing had wiped away the buildings in the city center. He and other members of his unit fashioned makeshift stretchers using straw mats and poles, and carried the wounded. That night, he lay down beside the road, but he was in such shock, he said, that he was unable to sleep.

The next day, August 7, he transported the bodies of victims by truck, and on August 8, helped cremate them near the Motoyasu River. The bodies were piled up high, with layers of logs in between, then set on fire. He couldn’t imagine what sort of bomb had caused such tragedy. He also came across many people who begged him for water. Mr. Wada said that he gave them some, thinking they would die shortly anyway.

He continued helping with these relief efforts until August 12, then returned to Etajima Island. Some members of his unit suffered from hair loss or bleeding gums as a result of their exposure to the bomb’s radiation. Mr. Wada’s reaction was more mild, and he endured only diarrhea for a week. Because the war ended before he was assigned to carry out a suicide attack, he admitted that he felt relieved. Still, he had mixed feelings. “If the war had lasted six more months, I would have died, too,” he said.

Mr. Wada said that he hopes young people today can appreciate how priceless it is to have the opportunity to live free and enjoyable lives. As he reflected on the many deaths he witnessed in the burnt ruins of the city, he said firmly, in this 72nd year since the atomic bombing, “Nuclear weapons can only lead to the destruction of human beings.” (Naruho Matsuzaki, 16, Tokitsuna Kawagishi, 16, and Miki Meguro, 16)

Go Okumoto, researcher of local battle sites

The army’s marine suicide attack unit was formed in 1944, when the tide of the war was turning against Japan. Gou Okumoto, 45, a resident of Etajima City and the captain of a ferry who researches local battle sites, told us that the unit forged into the fighting without proper equipment.

Special marine officer candidates, most of them in their late teens who had applied to participate, were assigned to the unit and trained with a special craft nicknamed “Maru-re.” The role of the unit involved attacking enemy ships that ventured into Japanese waters, not actively pursuing them. There were 53 squadrons, and each was comprised of 100 soldiers. After the members of the unit were trained on Shodoshima Island or Etajima Island, they were dispatched to the Philippines, which was part of the Japanese territories at the time, as well as Okinawa and parts of Kyushu.

The soldiers would board their crafts at night to carry out their missions. They approached the enemy ship, dropped a bomb called a depth charge, then retreated quickly because the weapon would explode in seven seconds. The aim of the attack was to blast a hole in the body of the enemy ship or damage its framework so that it would sink. However, because the “Maru-re” craft was not equipped with a gun or roof for defense, it was very vulnerable to machine-gun fire. It was also a difficult craft to operate. Under these circumstances, the unit finally turned into a suicide attack squad in which the soldiers conducted suicide attacks by crashing into the enemy ships with their boats.

The design of the “Maru-re” craft was simple so that it could be easily mass produced. The body was 5.6 meters long and 1.8 meters wide, and was made of a Japanese Zelkova frame covered only with waterproof plywood that was four to six millimeters thick. Because the craft was powered by an automobile engine, it was vulnerable to water and stalled frequently. The 250-kilogram depth charge, which was placed at the rear of the craft, was affixed only with wire.

Mr. Okumoto has turned his research on the suicide attack unit into a book. He said, “The lives of those who were killed, as well as the unit’s rescue efforts after the atomic bombing, have not been widely recognized. I would like many more people to be aware of this history.” (Honoka Hiramatsu, 14)

Satoru Ubuki, expert on the history of the A-bombing

To help with relief efforts in Hiroshima in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, the Akatsuki unit, which operated under the Army Shipping Command in Ujina, was dispatched to the disaster zone. The army’s marine suicide attack unit was part of the Akatsuki unit. What impact did the rescue activities by the military have? The junior writers interviewed Satoru Akira, 70, a resident of Kure, who is an expert on the history of the atomic bombing and Hiroshima’s post-war period.

The fact that the army took part in relief efforts after the Hiroshima bombing was unique compared to other places. Removing and cremating the dead was an important task for the army, as much as aiding the wounded, because it wanted to avoid unsanitary conditions and the loss of fighting spirit among the general public. According to Record of the A-bomb Disaster, roughly 36% of the total number of bodies were removed and cremated by the army within two weeks of the atomic bombing.

Because the unit stationed near Hiroshima Castle was decimated, the Akatsuki unit played a significant role in the relief efforts, as they were stationed in the adjacent area and suffered less damage in the A-bomb attack. After their rescue operations ended, the members of the unit who had been brought together from across Japan returned to their hometowns. Though they faced difficulties finding witnesses when they later applied for the Atomic Bomb Survivor's Certificate, a veterans’ association, which formed branches in many parts of Japan, assisted them with this need.

Many members of the the army’s marine suicide attack unit experienced the atomic bombing while in their late teens. Some suffered the effects of their exposure to the bomb’s radiation, such as a decrease in their white blood count. Mr. Ubuki said, “The youngsters who had already prepared themselves to serve as humans bombs and die in a suicide attack saved the lives of others. We should not forget this fact.” He added, “Japanese society of that time must be blamed, too, because it forced them into a situation, at a young age, where their health suffered as a result of their radiation exposure.” (Riho Kito, 16)

Junior writers’ impressions

Through the interview for this article, I learned about the army’s marine suicide attack unit, which Mr. Wada belonged to, for the first time. It was distressing for me to hear how young people like us were forced to endure harsh training and that many of them lost their lives when they crashed their small, fragile crafts into enemy ships. Also, when Mr. Wada told us that he had believed that dying in a suicide attack demonstrated a man’s true worth, my heart ached as I thought about how the young people of that time had to live amid conditions where they felt compelled to fight and sacrifice themselves for their country. (Naruho Matsuzaki)

This was the first time I took part in a telephone interview, but it was a bit difficult because I couldn’t see the person’s face directly. Still, I was impressed by the comments that were made by Mr. Ubuki, the person I interviwed. He told me, “It would be easier for you to understand this by relating the damages of the atomic bombing to current issues.” I want to continue working hard in my reporting. (Riho Kito)

I went to Etajima Island in person and interviewed Mr. Wada. The memories that he shared with me of August 6, the day Hiroshima was attacked, were beyond what I had imagined. When we climbed the mountain and I listened to his A-bomb experience, I felt as if I could see the big mushroom cloud with my own eyes as I looked out over the sea toward Hiroshima. I want to do my best to convey the A-bomb experiences of survivors like Mr. Wada to younger generations so that the world can continue to be a peaceful place. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi)

Mr. Wada said, “The atmosphere of that time made us think that dying from a suicide attack, without any hesitation, was just a matter of course.” This is hard for me to imagine, since I live in today’s Japan, which is not at war, but I think it’s horrible that so many people didn’t doubt such ideas at that time. So that an era like that won’t ever occur again, I really felt how important it is that we raise our voices and demand that war must never be repeated. (Miki Meguro)

I interviewed Mr. Okumoto. Though, before that, I didn’t know anything about the army’s marine suicide attack unit, I understood how hopeless the war was after I heard about the suicide attack unit and its flimsy “Maru-re” craft. I felt strongly that we have to shine more light on the many hidden aspects of history and reflect on the damage wrought by the atomic bombing more thoroughly. (Honoka Hiramatsu)

What is Peace Seeds?

Peace Seeds are the seeds which can be spread around the world by thinking about peace and the preciousness of life from various viewpoints. To fill this world with flowering smiles, 27 junior writers, from the first year of junior high school to the third year of senior high school, choose themes, gather information, and write articles.

(Originally published on July 20, 2017)