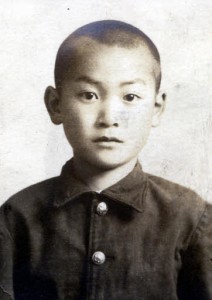

Survivors’ Stories: Tokuo Shimizu, 86, Saeki Ward, Hiroshima

Jan. 15, 2018

River under the hypocenter was filled with bodies

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Tokuo Shimizu kept his memories of the atomic bombing to himself: the hellish scene under the hypocenter he saw the day after; his sister’s death. At the age of 86, however, he decided that he wanted to share his A-bomb account with younger generations to convey a message of “no more war.”

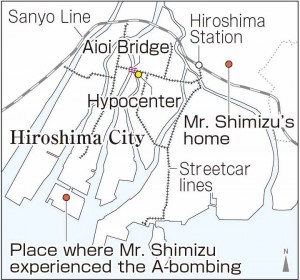

Back then, Mr. Shimizu was a second-year student at the Hiroshima Municipal Shipbuilding Engineering School (now the Hiroshima Municipal Commercial High School). On August 6, 1945, the day of the atomic bombing, he was at the Mitsubishi Heavy Industry Hiroshima Shipyard working as a mobilized student. He was helping to construct naval weapons intended for suicide attacks.

Suddenly, a brilliant flash of light poured into his workplace. At first, Mr. Shimizu thought that there had been a short-circuit at the shipyard. He sought refuge in a nearby air-raid shelter, and soon after, a huge mushroom cloud rose above the central part of the city. He spent that night in the shelter, worrying about his family, then headed to his home in the Onaga district (now part of Higashi Ward) early the next morning.

“I moved past people who were so badly burned that they no longer even looked human,” he said. “I had to try to avoid stepping on the bodies.” Under the eaves of one house, he saw several dead bodies, the heads submerged in a fire cistern. But because Mr. Shimizu was so thirsty, he pushed the bodies aside and drank from it. “It was strange to see mosquito larvae floating there in the water,” he said, “even in those circumstances.”

Mr. Shimizu was unable to forget the terrible sights he witnessed around the Aioi Bridge, which had been the target of the U.S. bomb. The river was filled with so many bodies that he couldn’t see the surface of the water. On the bridge was an American soldier who had been a prisoner of war. A man who looked like a military policeman was standing by him, urging people to accost him with sticks and stones.

When he finally reached home, he found that the house was badly damaged but had escaped fire. His mother was unhurt. However, his sister, Yasuko Hamada, then 27, became a victim of the bombing.

Yasuko was living with her husband’s family but fled back home. She went searching for her missing daughter, Mieko, who was a first-year student at Kanzaki National School. Then Yasuko became ill and lay in bed. She grew delirious and said that she wanted to eat zenzai (a kind of thick, sweet soup made from azuki bean paste, with a piece of rice cake), so the family begged a farmer and managed to obtain some scanty ingredients. By the time the dish was ready, Yasuko had already taken her last breath. “I wanted her to eat it...” Mr. Shimizu could find no more words to talk about his sister.

Yasuko’s husband was severely burned in the bombing and died before the war would end. Their daughter Mieko was never found. About 20 years ago, Mr. Shimizu’s path crossed with the late Keiji Nakazawa, the author of the manga series Barefoot Gen. Mr. Nakazawa told him that Mieko was with him near the school gate and they were blown off their feet by the A-bomb blast.

Mr. Shimizu also lost close friends. All the first-year students from his school who were mobilized to the area near where the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum now stands were killed. One of his schoolmates was from a national school who had waited for a year to enter the Shipbuilding Engineering School because it was a popular school. Mr. Shimizu’s heart still aches when he thinks of these friends, who died in regret.

Mr. Shimizu himself suffered from acute symptoms of radiation sickness, including hair loss and bleeding from his gums. During the war, he lost his father and, after the war ended, he endured a difficult time when food was scarce. He picked weeds that grew along the railway tracks to eat, and earned meager wages from the black market.

In 1949, he moved to a liquor shop in Itsukaichi run by the family that another sister had married into. There, he met his late wife, Sachie. He ran the shop for many years with her. He served as the first chair of the shopping district promotion association of Coin Street, which was named after the Hiroshima Branch of Japan Mint. He and other local people built a shrine, calling it the “Rich Inari Shrine,” on the roof of the shop. He devoted himself to promoting the local economy.

Mr. Shimizu currently lives with a grandchild’s family, and has been blessed with four great-grandchildren. “Without everyone’s efforts after the war, Hiroshima wouldn’t have recovered and become the city it is now. We should never ever wage war again,” he said, seeing his own life in the story of Hiroshima’s recovery.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Burdened by such painful memories

It broke my heart to see Mr. Shimizu choking out the words when he told us about his sister’s death. I realized that people like Mr. Shimizu, who spoke merrily about the funny goods connected to the “Rich Inari Shrine,” are burdened in silence with the pain of bitter memories. After hearing the story of this A-bomb survivor, I thought about how important it is that we sincerely listen to him and try to appreciate his feelings. (Naruho Matsuzaki, 17)

Appreciating the efforts to rebuild the city

Mr. Shimizu told us again and again: “We have to create a peaceful world.” His words left a deep impression on me because they come from his actual experience. They carry weight compared to the words of young people who know only about peaceful times in Japan. Thanks to the tremendous efforts made by the older generations, the devastated city of Hiroshima was able to recover and become a city full of greenery and life. I respect them, and thank them, for their enormous efforts. (Marina Misaki, 18)

(Originally published on January 15, 2018)

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Tokuo Shimizu kept his memories of the atomic bombing to himself: the hellish scene under the hypocenter he saw the day after; his sister’s death. At the age of 86, however, he decided that he wanted to share his A-bomb account with younger generations to convey a message of “no more war.”

Back then, Mr. Shimizu was a second-year student at the Hiroshima Municipal Shipbuilding Engineering School (now the Hiroshima Municipal Commercial High School). On August 6, 1945, the day of the atomic bombing, he was at the Mitsubishi Heavy Industry Hiroshima Shipyard working as a mobilized student. He was helping to construct naval weapons intended for suicide attacks.

Suddenly, a brilliant flash of light poured into his workplace. At first, Mr. Shimizu thought that there had been a short-circuit at the shipyard. He sought refuge in a nearby air-raid shelter, and soon after, a huge mushroom cloud rose above the central part of the city. He spent that night in the shelter, worrying about his family, then headed to his home in the Onaga district (now part of Higashi Ward) early the next morning.

“I moved past people who were so badly burned that they no longer even looked human,” he said. “I had to try to avoid stepping on the bodies.” Under the eaves of one house, he saw several dead bodies, the heads submerged in a fire cistern. But because Mr. Shimizu was so thirsty, he pushed the bodies aside and drank from it. “It was strange to see mosquito larvae floating there in the water,” he said, “even in those circumstances.”

Mr. Shimizu was unable to forget the terrible sights he witnessed around the Aioi Bridge, which had been the target of the U.S. bomb. The river was filled with so many bodies that he couldn’t see the surface of the water. On the bridge was an American soldier who had been a prisoner of war. A man who looked like a military policeman was standing by him, urging people to accost him with sticks and stones.

When he finally reached home, he found that the house was badly damaged but had escaped fire. His mother was unhurt. However, his sister, Yasuko Hamada, then 27, became a victim of the bombing.

Yasuko was living with her husband’s family but fled back home. She went searching for her missing daughter, Mieko, who was a first-year student at Kanzaki National School. Then Yasuko became ill and lay in bed. She grew delirious and said that she wanted to eat zenzai (a kind of thick, sweet soup made from azuki bean paste, with a piece of rice cake), so the family begged a farmer and managed to obtain some scanty ingredients. By the time the dish was ready, Yasuko had already taken her last breath. “I wanted her to eat it...” Mr. Shimizu could find no more words to talk about his sister.

Yasuko’s husband was severely burned in the bombing and died before the war would end. Their daughter Mieko was never found. About 20 years ago, Mr. Shimizu’s path crossed with the late Keiji Nakazawa, the author of the manga series Barefoot Gen. Mr. Nakazawa told him that Mieko was with him near the school gate and they were blown off their feet by the A-bomb blast.

Mr. Shimizu also lost close friends. All the first-year students from his school who were mobilized to the area near where the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum now stands were killed. One of his schoolmates was from a national school who had waited for a year to enter the Shipbuilding Engineering School because it was a popular school. Mr. Shimizu’s heart still aches when he thinks of these friends, who died in regret.

Mr. Shimizu himself suffered from acute symptoms of radiation sickness, including hair loss and bleeding from his gums. During the war, he lost his father and, after the war ended, he endured a difficult time when food was scarce. He picked weeds that grew along the railway tracks to eat, and earned meager wages from the black market.

In 1949, he moved to a liquor shop in Itsukaichi run by the family that another sister had married into. There, he met his late wife, Sachie. He ran the shop for many years with her. He served as the first chair of the shopping district promotion association of Coin Street, which was named after the Hiroshima Branch of Japan Mint. He and other local people built a shrine, calling it the “Rich Inari Shrine,” on the roof of the shop. He devoted himself to promoting the local economy.

Mr. Shimizu currently lives with a grandchild’s family, and has been blessed with four great-grandchildren. “Without everyone’s efforts after the war, Hiroshima wouldn’t have recovered and become the city it is now. We should never ever wage war again,” he said, seeing his own life in the story of Hiroshima’s recovery.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Burdened by such painful memories

It broke my heart to see Mr. Shimizu choking out the words when he told us about his sister’s death. I realized that people like Mr. Shimizu, who spoke merrily about the funny goods connected to the “Rich Inari Shrine,” are burdened in silence with the pain of bitter memories. After hearing the story of this A-bomb survivor, I thought about how important it is that we sincerely listen to him and try to appreciate his feelings. (Naruho Matsuzaki, 17)

Appreciating the efforts to rebuild the city

Mr. Shimizu told us again and again: “We have to create a peaceful world.” His words left a deep impression on me because they come from his actual experience. They carry weight compared to the words of young people who know only about peaceful times in Japan. Thanks to the tremendous efforts made by the older generations, the devastated city of Hiroshima was able to recover and become a city full of greenery and life. I respect them, and thank them, for their enormous efforts. (Marina Misaki, 18)

(Originally published on January 15, 2018)