Survivors’ Stories: Masako Kochi, 89, Higashi Ward, Hiroshima

Jun. 4, 2018

House burned to the ground, family members reduced to bones

by Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer

Masako Kochi (née Tomotake), 89, still shares her experience of the atomic bombing. “I believe in peace. I would never want to waste the lives of those who died regrettable deaths, so I continue to share my experience for posterity,” she explained.

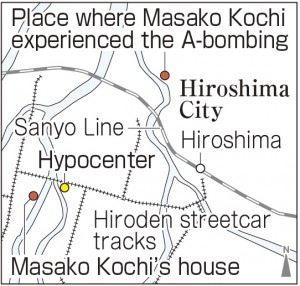

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Kochi was 16 and a fourth-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ High School (now Funairi High School). Her house was in Tsukamoto-cho (now part of Naka Ward). Her father Gunichi, 48, ran a wholesale store mainly handling textile products. Because the factory where she had been mobilized to work was closed on August 6, she went to her grandmother’s house in the Ushita district, 2.1 kilometers from the hypocenter, the night before. Her parents had urged her to stay with her grandmother, saying, “If there’s an air raid, the whole family might be killed.”

She was happy because it was the first day she had off in a long time. She enjoyed the early morning, walking through her grandmother’s garden and near the house. But the moment she stepped back inside, she felt an intense flash and became buried under the collapsed building. When she came to, she saw a sliver of light and made her way toward it to escape. She discovered that her body was now pierced with bits of broken glass. When she rushed into the bomb shelter outside the house, she found her grandmother there, covered in blood. They decided to flee to the mountains together.

Seeing the urban area of Hiroshima in flames, she prayed fervently for the safety of her family. She tried to go home the next day, and the day after that, but was unable to make it because of the huge number of dead bodies. Finally, on August 9, she managed to reach her house and found that it had burned to the ground. At the entrance were her father’s bones and the skeleton of her 18-year-old sister, Nobuko, was sitting in the kitchen. Her mother, Masano, 46, was lying on the floor of the kitchen; the upper half of her body was charred black and the lower half was reduced to bones. There was a kitchen knife on the bones of her foot. Judging from the situation, Ms. Kochi believes that they perished on the spot.

Her body trembling, Ms. Kochi then gathered up her family’s remains, placing them in her air-raid hood. She then held the bones close to her chest and wondered where she should take her own life. She thought she could die in the river, but the stone steps of the riverbank were clogged with bodies and she was unable to go down them. At that point she thought of her grandmother, assuming she would be worried, and made her way back to her grandmother’s house.

Later, her mother’s relatives came and carried her in a two-wheeled cart to the village of Kameyama (now part of Asakita Ward), where her maternal grandparents lived. She came down with symptoms of radiation sickness, including hair loss, black spots on her body, high fever, and diarrhea, and spent days in a state of clouded consciousness. Two months passed and she began to regain better health.

After the war, Ms. Kochi became an elementary school teacher and continued in this role until she reached the mandatory retirement age of 60. She got married at the age of 24 and has two children and four grandchildren. During her time as a teacher, she began to share her experience of the atomic bombing. “When I saw children pretending to be soldiers, I decided to talk about my experience of the atomic bombing, though I didn’t want to bring back those painful memories,” she said.

The Peace Declaration read out by the mayor of Hiroshima on the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing quoted Ms. Kochi’s words: “Expanding ever wider the circle of harmony that includes your family, friends, and neighbors links directly to world peace. Empathy, kindness, solidarity—these are not just intellectual concepts; we have to feel them in our bones.”

Being faithful to her own words, whenever Ms. Kochi shares her experience of the atomic bombing, which is still deeply seared into her mind, she always stresses the importance of building a peaceful society, through compassion, that is free from bullying and fighting. She hopes to continue sharing her experience as long as she possibly can.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Thankful for being able to receive an education

I was deeply impressed by Ms. Kochi’s words that being considerate to friends and family members can lead to peace. I thought I should express my gratitude to the people around me, who support me, and I should treat them nicely. Ms. Kochi also stressed that today’s teenagers are fortunate to have the opportunity to receive an education. She told us that she had dreamed of going to high school but then students were mobilized to work at factories and weren’t able to study. I will pursue my school work while appreciating how fortunate I am to be able to study. (Yui Morimoto, 14)

Feeling once again that the atomic bombing is unforgivable

When she passes the place where her house was located, near the Aioi Bridge, Ms. Kochi remembers how she enjoyed roller skating there…but also how she found the remains of her family members and went to the riverbank to kill herself. Her heart still aches when she recalls the numerous bodies that were in the river. The place where people spent their childhood should be filled with fond memories. But Ms. Kochi has very sad memories, too. Her story made me feel, once again, that the atomic bombing was unforgivable. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

(Originally published on June 4, 2018)

by Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer

Masako Kochi (née Tomotake), 89, still shares her experience of the atomic bombing. “I believe in peace. I would never want to waste the lives of those who died regrettable deaths, so I continue to share my experience for posterity,” she explained.

At the time of the atomic bombing, Ms. Kochi was 16 and a fourth-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ High School (now Funairi High School). Her house was in Tsukamoto-cho (now part of Naka Ward). Her father Gunichi, 48, ran a wholesale store mainly handling textile products. Because the factory where she had been mobilized to work was closed on August 6, she went to her grandmother’s house in the Ushita district, 2.1 kilometers from the hypocenter, the night before. Her parents had urged her to stay with her grandmother, saying, “If there’s an air raid, the whole family might be killed.”

She was happy because it was the first day she had off in a long time. She enjoyed the early morning, walking through her grandmother’s garden and near the house. But the moment she stepped back inside, she felt an intense flash and became buried under the collapsed building. When she came to, she saw a sliver of light and made her way toward it to escape. She discovered that her body was now pierced with bits of broken glass. When she rushed into the bomb shelter outside the house, she found her grandmother there, covered in blood. They decided to flee to the mountains together.

Seeing the urban area of Hiroshima in flames, she prayed fervently for the safety of her family. She tried to go home the next day, and the day after that, but was unable to make it because of the huge number of dead bodies. Finally, on August 9, she managed to reach her house and found that it had burned to the ground. At the entrance were her father’s bones and the skeleton of her 18-year-old sister, Nobuko, was sitting in the kitchen. Her mother, Masano, 46, was lying on the floor of the kitchen; the upper half of her body was charred black and the lower half was reduced to bones. There was a kitchen knife on the bones of her foot. Judging from the situation, Ms. Kochi believes that they perished on the spot.

Her body trembling, Ms. Kochi then gathered up her family’s remains, placing them in her air-raid hood. She then held the bones close to her chest and wondered where she should take her own life. She thought she could die in the river, but the stone steps of the riverbank were clogged with bodies and she was unable to go down them. At that point she thought of her grandmother, assuming she would be worried, and made her way back to her grandmother’s house.

Later, her mother’s relatives came and carried her in a two-wheeled cart to the village of Kameyama (now part of Asakita Ward), where her maternal grandparents lived. She came down with symptoms of radiation sickness, including hair loss, black spots on her body, high fever, and diarrhea, and spent days in a state of clouded consciousness. Two months passed and she began to regain better health.

After the war, Ms. Kochi became an elementary school teacher and continued in this role until she reached the mandatory retirement age of 60. She got married at the age of 24 and has two children and four grandchildren. During her time as a teacher, she began to share her experience of the atomic bombing. “When I saw children pretending to be soldiers, I decided to talk about my experience of the atomic bombing, though I didn’t want to bring back those painful memories,” she said.

The Peace Declaration read out by the mayor of Hiroshima on the 70th anniversary of the atomic bombing quoted Ms. Kochi’s words: “Expanding ever wider the circle of harmony that includes your family, friends, and neighbors links directly to world peace. Empathy, kindness, solidarity—these are not just intellectual concepts; we have to feel them in our bones.”

Being faithful to her own words, whenever Ms. Kochi shares her experience of the atomic bombing, which is still deeply seared into her mind, she always stresses the importance of building a peaceful society, through compassion, that is free from bullying and fighting. She hopes to continue sharing her experience as long as she possibly can.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Thankful for being able to receive an education

I was deeply impressed by Ms. Kochi’s words that being considerate to friends and family members can lead to peace. I thought I should express my gratitude to the people around me, who support me, and I should treat them nicely. Ms. Kochi also stressed that today’s teenagers are fortunate to have the opportunity to receive an education. She told us that she had dreamed of going to high school but then students were mobilized to work at factories and weren’t able to study. I will pursue my school work while appreciating how fortunate I am to be able to study. (Yui Morimoto, 14)

Feeling once again that the atomic bombing is unforgivable

When she passes the place where her house was located, near the Aioi Bridge, Ms. Kochi remembers how she enjoyed roller skating there…but also how she found the remains of her family members and went to the riverbank to kill herself. Her heart still aches when she recalls the numerous bodies that were in the river. The place where people spent their childhood should be filled with fond memories. But Ms. Kochi has very sad memories, too. Her story made me feel, once again, that the atomic bombing was unforgivable. (Shiho Fujii, 16)

(Originally published on June 4, 2018)