Survivors’ Stories: Toshiaki Furusawa, 86, Hiroshima: Fate determined by work shift

Jul. 10, 2018

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

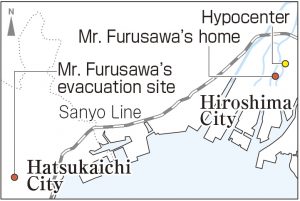

The home of Toshiaki Furusawa, 86, was located in Nakajima-shinmachi (in today’s Naka Ward), just south of where the Peace Memorial Park now lies. When Mr. Furusawa, then 13, returned home from his evacuation site two days after the atomic bombing, he found that the whole neighborhood, including his own house, had been destroyed by fire. Standing at the spot where his house had stood, about 700 meters from the hypocenter, he could see Hijiyama Hill and Ninoshima Island, which seemed so close without any buildings blocking his view. It felt to him like the city of Hiroshima had shrunk.

Nakajima-shinmachi was in the city center, with the Hiroshima Prefectural Office and the Prefectural Hospital nearby. As a child, the area had been his playground, where he would romp about and was often scolded for his antics. In the spring of 1945, Mr. Furusawa entered Shudo Middle School. Soon after that, his family was forced to evacuate to the village of Miyauchi (in today’s Hatsukaichi), where his mother was from, because his house was one of those targeted for demolition to create a fire break in the event of air raids. He went to school from the village.

It was “fate,” he said, that the first-year students were relieved of this demolition work on August 6. They had been mobilized, until August 5, to help with the war effort by tearing down homes in Zakoba-cho (in today’s Naka Ward), near City Hall. However, the second-year students took over this work on August 6 because the first-year students were exhausted and need a day off to rest.

Mr. Furusawa was at his evacuation site when he experienced a sudden flash of purple light and a great roar. There was then commotion in the area with people saying that Hiroshima was apparently hit by a big bomb. Mr. Furusawa was worried about his father, Masutaro, who was working in the city. Masutaro returned that evening on foot, his body bleeding badly.

On August 8, he entered the city in the aftermath of the bombing with his mother, Shigemi, and his sister, Yoko, to check on their house. This is when they were exposed to the atomic bomb’s radiation. They walked from Koi and crossed the railway bridge. The railway ties were now like charcoal, and the river was filled with bodies. He saw the legs of four or five people who were upright but their heads were submerged in a fire cistern. They were all dead. It was a horrific sight.

There was still smoke rising from the smoldering fires. They were able to locate the site of their house in the burnt-out city thanks to the paving stones outside the front door, which pointed to the spot. His mother urged him to write their names on a scrap of wood with a piece of charcoal, along with a message saying that they were alive and would be in Miyauchi.

With the terrible stench of dead bodies hanging in the air, they searched for their relatives but had difficulty finding them. They persisted in their search for his father’s younger sister, who lived in Funairi Saiwai-cho (in today’s Naka Ward), until they were finally reunited on the grounds of Hiroshima Second Middle School (now Kanon High School) on around August 10. Another relative, who was the same age as Mr. Furusawa and a student at Hiroshima Second Middle School, was also killed by the atomic bomb. The body was wrapped in bandages when it arrived in Miyauchi.

After the war, his father was unable to work and so Mr. Furusawa had to support the family. He started working at a river improvement project when he was in his second year of middle school. He continued this work on weekends even after advancing to Hiroshima Prefectural Hatsukaichi Senior High School, which he attended on weekdays. He studied hard to become a doctor, partly due to the desire of his mother, who had previously been ill.

After Mr. Furusawa’s father passed away, he gave up medicine. When he was in his 30s, working as a company employee, he read about the job of management consultant in the newspaper. He then vowed to himself to become a consultant someday. He eventually graduated from a night course at Hiroshima University and fulfilled his dream of becoming a management consultant.

At first, it was hard for him to be in Hiroshima when the anniversary of the atomic bombing approached, so he intentionally sought to travel to the Kanto region for work during that time. Looking back, Mr. Furusawa said, “I was running away from the bombing by devoting myself solely to work.” After establishing a vocational school in Hiroshima, he regained a sense of equilibrium as his workload increased.

Mr. Furusawa is now the president of an educational corporation which runs private schools, including Hiroshima Cosmopolitan University. At his schools he gives talks about the tragedy of the atomic bombing and the importance of peace because “it is the survivors’ responsibility to do more than what the victims could do.” He has never forgotten the 130 second-year students from Shudo Middle School who lost their lives in the bombing while involved in the demolition work. When he walks through the Peace Memorial Park, which is close to his home, he always joins his hands in prayer.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I can now imagine the burnt ruins of the city

It sometimes pains me to recall Mr. Furusawa’s story because I can now imagine the city in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, something that I never experienced myself. Mr. Furusawa said that he could see the entire city from the site of his home after the bombing. I could never imagine the burnt ruins of the city before I heard his story. The city is now crowded with buildings, but I will remember the devastated city of 73 years ago. (Hitoha Katsura, 13)

I’m grateful for people’s support and the chance to study

Mr. Furusawa endured a life of poverty while working his way through junior high school and high school. Even after he went out into the world, he continued studying and he graduated from college and made his dream come true. His story made me realize keenly that I mustn’t take my life today for granted. I have college entrance examinations coming up. I won’t forget the people who are supporting me and providing me with an environment where I can study without worries. I’ll do my best. (Honoka Ikeda, 18)

Articles in the “Handing Down Memories” series can be found in the “Survivors’ Stories” section of this website. We are also seeking A-bomb survivors who can share their A-bomb accounts with children of their grandchildren’s generation. Please contact us at 082-236-2801.

(Originally published on July 10, 2018)

The home of Toshiaki Furusawa, 86, was located in Nakajima-shinmachi (in today’s Naka Ward), just south of where the Peace Memorial Park now lies. When Mr. Furusawa, then 13, returned home from his evacuation site two days after the atomic bombing, he found that the whole neighborhood, including his own house, had been destroyed by fire. Standing at the spot where his house had stood, about 700 meters from the hypocenter, he could see Hijiyama Hill and Ninoshima Island, which seemed so close without any buildings blocking his view. It felt to him like the city of Hiroshima had shrunk.

Nakajima-shinmachi was in the city center, with the Hiroshima Prefectural Office and the Prefectural Hospital nearby. As a child, the area had been his playground, where he would romp about and was often scolded for his antics. In the spring of 1945, Mr. Furusawa entered Shudo Middle School. Soon after that, his family was forced to evacuate to the village of Miyauchi (in today’s Hatsukaichi), where his mother was from, because his house was one of those targeted for demolition to create a fire break in the event of air raids. He went to school from the village.

It was “fate,” he said, that the first-year students were relieved of this demolition work on August 6. They had been mobilized, until August 5, to help with the war effort by tearing down homes in Zakoba-cho (in today’s Naka Ward), near City Hall. However, the second-year students took over this work on August 6 because the first-year students were exhausted and need a day off to rest.

Mr. Furusawa was at his evacuation site when he experienced a sudden flash of purple light and a great roar. There was then commotion in the area with people saying that Hiroshima was apparently hit by a big bomb. Mr. Furusawa was worried about his father, Masutaro, who was working in the city. Masutaro returned that evening on foot, his body bleeding badly.

On August 8, he entered the city in the aftermath of the bombing with his mother, Shigemi, and his sister, Yoko, to check on their house. This is when they were exposed to the atomic bomb’s radiation. They walked from Koi and crossed the railway bridge. The railway ties were now like charcoal, and the river was filled with bodies. He saw the legs of four or five people who were upright but their heads were submerged in a fire cistern. They were all dead. It was a horrific sight.

There was still smoke rising from the smoldering fires. They were able to locate the site of their house in the burnt-out city thanks to the paving stones outside the front door, which pointed to the spot. His mother urged him to write their names on a scrap of wood with a piece of charcoal, along with a message saying that they were alive and would be in Miyauchi.

With the terrible stench of dead bodies hanging in the air, they searched for their relatives but had difficulty finding them. They persisted in their search for his father’s younger sister, who lived in Funairi Saiwai-cho (in today’s Naka Ward), until they were finally reunited on the grounds of Hiroshima Second Middle School (now Kanon High School) on around August 10. Another relative, who was the same age as Mr. Furusawa and a student at Hiroshima Second Middle School, was also killed by the atomic bomb. The body was wrapped in bandages when it arrived in Miyauchi.

After the war, his father was unable to work and so Mr. Furusawa had to support the family. He started working at a river improvement project when he was in his second year of middle school. He continued this work on weekends even after advancing to Hiroshima Prefectural Hatsukaichi Senior High School, which he attended on weekdays. He studied hard to become a doctor, partly due to the desire of his mother, who had previously been ill.

After Mr. Furusawa’s father passed away, he gave up medicine. When he was in his 30s, working as a company employee, he read about the job of management consultant in the newspaper. He then vowed to himself to become a consultant someday. He eventually graduated from a night course at Hiroshima University and fulfilled his dream of becoming a management consultant.

At first, it was hard for him to be in Hiroshima when the anniversary of the atomic bombing approached, so he intentionally sought to travel to the Kanto region for work during that time. Looking back, Mr. Furusawa said, “I was running away from the bombing by devoting myself solely to work.” After establishing a vocational school in Hiroshima, he regained a sense of equilibrium as his workload increased.

Mr. Furusawa is now the president of an educational corporation which runs private schools, including Hiroshima Cosmopolitan University. At his schools he gives talks about the tragedy of the atomic bombing and the importance of peace because “it is the survivors’ responsibility to do more than what the victims could do.” He has never forgotten the 130 second-year students from Shudo Middle School who lost their lives in the bombing while involved in the demolition work. When he walks through the Peace Memorial Park, which is close to his home, he always joins his hands in prayer.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I can now imagine the burnt ruins of the city

It sometimes pains me to recall Mr. Furusawa’s story because I can now imagine the city in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, something that I never experienced myself. Mr. Furusawa said that he could see the entire city from the site of his home after the bombing. I could never imagine the burnt ruins of the city before I heard his story. The city is now crowded with buildings, but I will remember the devastated city of 73 years ago. (Hitoha Katsura, 13)

I’m grateful for people’s support and the chance to study

Mr. Furusawa endured a life of poverty while working his way through junior high school and high school. Even after he went out into the world, he continued studying and he graduated from college and made his dream come true. His story made me realize keenly that I mustn’t take my life today for granted. I have college entrance examinations coming up. I won’t forget the people who are supporting me and providing me with an environment where I can study without worries. I’ll do my best. (Honoka Ikeda, 18)

Articles in the “Handing Down Memories” series can be found in the “Survivors’ Stories” section of this website. We are also seeking A-bomb survivors who can share their A-bomb accounts with children of their grandchildren’s generation. Please contact us at 082-236-2801.

(Originally published on July 10, 2018)