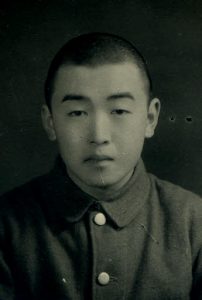

Survivors’ Stories: Hiroyuki Miyagawa, 88, Hiroshima: Feeling guilt over having survived

Aug. 6, 2018

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Hiroyuki Miyagawa, 88, was an English teacher at Motomachi Senior High School, located in Naka Ward, for many years and also put his heart and soul into peace activities. He said, “All five members of my family survived the atomic bombing.” That is why he has not been able to escape from the survivor’s guilt he has felt since that day 73 years ago.

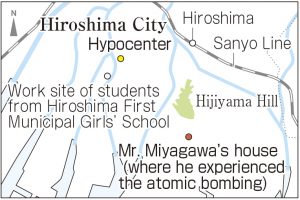

Mr. Miyagawa’s father, Zoroku Miyagawa, who died in 1975 at the age of 74, was the principal of Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (now Funairi High School). On the morning of August 6, 1945, Zoroku was in Kobiki-cho (now part of Naka Ward), about 500 meters from the hypocenter. He was there with seven teachers because about 540 first- and second-year students of the school were helping to tear down buildings to create a fire lane.

After the students gathered for the morning assembly and Zoroku had them begin their work, he went to the educational section of the prefectural government, located near Hiroshima Station, at around 8 a.m. Just minutes later, the atomic bomb exploded. The many female students, around 13 years old, and his colleagues were hit by the bomb blast and heat rays, and all of them were burned to death.

Only Mr. Miyagawa and his mother, Tomoe Miyagawa, who died in 2004 at the age of 92, were at home, located in Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward), 2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. His brother, who was two years younger, had been evacuated earlier, along with his classmates, to Hachihonmatsu-cho (now part of the city of Higashi-hiroshima) in the event that the city became a target of air raids. His sister, who was still small, had been evacuated to Kagawa Prefecture, where Zoroku’s hometown was located. Mr. Miyagawa, a fourth-year student at the junior high school affiliated with the Hiroshima Higher Normal School (now the senior high school affiliated with Hiroshima University), went to the former Army Clothing Depot each day to work for the war effort, but he developed a rash on his face that day and so stayed home.

In the sweltering summer heat, Mr. Miyagawa was shirtless as he read a book and then heard the enormous roar of a B-29 bomber. It seemed to him that the plane was flying at a unusually low altitude and he went out into the garden behind his house. The moment he looked up at the sky, he saw bright yellow columns of flame rising above the city center and felt heat on his back and on his left cheek.

He then found himself lying on his face amid the wreckage of his house. He felt a stinging pain from burns to his face, left hand, and back. The A-bomb blast had toppled the walls and doors and shoji screens, as if a great earthquake had destroyed their home.

He heard his mother, Tomoe, calling his name and went in the direction of her voice. He found her clinging to a fence in the field in front of their house. She was trembling. Hundreds of people from the city center then streamed into the narrow street that ran alongside their house. Their skin was blackened and they were half-naked, in tattered clothing. They were bleeding all over, from their heads and bodies, and looked like ghosts.

Mr. Miyagawa went to an air-raid shelter at the foot of Hijiyama Hill with his mother and father, who had returned home. People crammed into the shelter, one after another, bleeding badly from their wounds. A girl whose face was red from her burns was crying and shouting. A woman whose whole body was burned was groaning with pain, moaning “Help me. It hurts,” but no one could help her. Everyone had gone beyond the bounds of rational thinking.

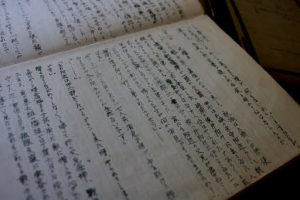

Starting the next day, Zoroku began staying at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School, located in Funairikawaguchi-cho (now part of Naka Ward), and was busy confirming the safety of students. In a diary from that time, which Mr. Miyagawa has long kept with care, it was noted that parents of some students also visited Zoroku’s house in Minami-machi, because they wanted to know if Zoroku knew anything about the whereabouts of their daughters, who hadn’t returned home. But they left with their heads bowed. Mr. Miyagawa said, “It seems they blamed my father for their loss, even at the school, telling him to give them back their daughter.”

Later, Mr. Miyagawa went on to Kyoto University’s Faculty of Letters. In 1951, during the U.S. occupation of Japan, he was involved in an atomic bomb exhibition that was held at a department store in Kyoto by students of Kyoto University. He also published a volume of A-bomb accounts with a group of other students after they listened to the experiences of A-bomb survivors in Kyoto and Hiroshima.

When the Korean War broke out during the time of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, such atomic bomb exhibitions, which conveyed the inhuman consequences of the atomic bombings, were met by a powerful reaction. Among those that Mr. Miyagawa worked with were students who became well-known writers, including Sakyo Komatsu (1931-2011) and Kazumi Takahashi (1931-1971).

When Mr. Miyagawa reached retirement age and left Motomachi Senior High School at the age of 60, he joined the Hiroshima o Kataru Kai, a group that shared their experiences of the Hiroshima bombing, and began to relate his account to students on school trips. He also went to South Korea to lend his support to A-bomb survivors there. He said, “The A-bomb survivors in South Korea have been neglected and I want to help them.” He has made many visits to South Korea and worked hard to provide the survivors with medical support.

In mid-July, prior to the A-bomb anniversary on August 6, Mr. Miyagawa put his hands together in a prayer for peace at the A-bomb Monument of Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School, located at the foot of Peace Bridge. Before his death, Zoroku wrote in a record compiled by the school’s alumni association to remember the victims: “Whenever I go across Peace Bridge, I can still picture the students and my heart aches with sorrow.” Mr. Miyagawa, who is now 88 years old, said, “What would be best is a peaceful world where everyone can live safely each day. The loss of human life in war must never be repeated.” This is his fervent desire.

Teenagers’ impressions

Shocked by survivor’s guilt

The parents of his father’s students complained bitterly, “All of your family members have survived. Give us back our daughter.” Mr. Miyagawa said in a pained voice, “I felt more sorry than lucky that my family had escaped injury.” I was shocked by his words. The atomic bombing even made him feel guilty for having survived. I’m sure there are many people who still have invisible wounds from the war. I want to meet more of them in the future and learn from them. (Akane Sato, 15)

Learning about A-bomb survivors in South Korea

Mr. Miyagawa has worked with others to lend support to A-bomb survivors in South Korea for many years. There isn’t a lot of interest in A-bomb survivors in South Korea, and there was no support system for these people. I realized that there’s a gap between South Korea and Hiroshima in this way, because in Hiroshima, A-bomb survivors share their experiences and it’s common for schools to have a peace studies program. I had known that there were A-bomb survivors living in other countries, but this was the first time I learned about the large gap in support. I want to broaden my perspective and learn more about the A-bomb survivors in South Korea. (Miki Meguro, 15)

(Originally published on August 6, 2018)

Hiroyuki Miyagawa, 88, was an English teacher at Motomachi Senior High School, located in Naka Ward, for many years and also put his heart and soul into peace activities. He said, “All five members of my family survived the atomic bombing.” That is why he has not been able to escape from the survivor’s guilt he has felt since that day 73 years ago.

Mr. Miyagawa’s father, Zoroku Miyagawa, who died in 1975 at the age of 74, was the principal of Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School (now Funairi High School). On the morning of August 6, 1945, Zoroku was in Kobiki-cho (now part of Naka Ward), about 500 meters from the hypocenter. He was there with seven teachers because about 540 first- and second-year students of the school were helping to tear down buildings to create a fire lane.

After the students gathered for the morning assembly and Zoroku had them begin their work, he went to the educational section of the prefectural government, located near Hiroshima Station, at around 8 a.m. Just minutes later, the atomic bomb exploded. The many female students, around 13 years old, and his colleagues were hit by the bomb blast and heat rays, and all of them were burned to death.

Only Mr. Miyagawa and his mother, Tomoe Miyagawa, who died in 2004 at the age of 92, were at home, located in Minami-machi (now part of Minami Ward), 2.3 kilometers from the hypocenter. His brother, who was two years younger, had been evacuated earlier, along with his classmates, to Hachihonmatsu-cho (now part of the city of Higashi-hiroshima) in the event that the city became a target of air raids. His sister, who was still small, had been evacuated to Kagawa Prefecture, where Zoroku’s hometown was located. Mr. Miyagawa, a fourth-year student at the junior high school affiliated with the Hiroshima Higher Normal School (now the senior high school affiliated with Hiroshima University), went to the former Army Clothing Depot each day to work for the war effort, but he developed a rash on his face that day and so stayed home.

In the sweltering summer heat, Mr. Miyagawa was shirtless as he read a book and then heard the enormous roar of a B-29 bomber. It seemed to him that the plane was flying at a unusually low altitude and he went out into the garden behind his house. The moment he looked up at the sky, he saw bright yellow columns of flame rising above the city center and felt heat on his back and on his left cheek.

He then found himself lying on his face amid the wreckage of his house. He felt a stinging pain from burns to his face, left hand, and back. The A-bomb blast had toppled the walls and doors and shoji screens, as if a great earthquake had destroyed their home.

He heard his mother, Tomoe, calling his name and went in the direction of her voice. He found her clinging to a fence in the field in front of their house. She was trembling. Hundreds of people from the city center then streamed into the narrow street that ran alongside their house. Their skin was blackened and they were half-naked, in tattered clothing. They were bleeding all over, from their heads and bodies, and looked like ghosts.

Mr. Miyagawa went to an air-raid shelter at the foot of Hijiyama Hill with his mother and father, who had returned home. People crammed into the shelter, one after another, bleeding badly from their wounds. A girl whose face was red from her burns was crying and shouting. A woman whose whole body was burned was groaning with pain, moaning “Help me. It hurts,” but no one could help her. Everyone had gone beyond the bounds of rational thinking.

Starting the next day, Zoroku began staying at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School, located in Funairikawaguchi-cho (now part of Naka Ward), and was busy confirming the safety of students. In a diary from that time, which Mr. Miyagawa has long kept with care, it was noted that parents of some students also visited Zoroku’s house in Minami-machi, because they wanted to know if Zoroku knew anything about the whereabouts of their daughters, who hadn’t returned home. But they left with their heads bowed. Mr. Miyagawa said, “It seems they blamed my father for their loss, even at the school, telling him to give them back their daughter.”

Later, Mr. Miyagawa went on to Kyoto University’s Faculty of Letters. In 1951, during the U.S. occupation of Japan, he was involved in an atomic bomb exhibition that was held at a department store in Kyoto by students of Kyoto University. He also published a volume of A-bomb accounts with a group of other students after they listened to the experiences of A-bomb survivors in Kyoto and Hiroshima.

When the Korean War broke out during the time of the Cold War between the United States and the Soviet Union, such atomic bomb exhibitions, which conveyed the inhuman consequences of the atomic bombings, were met by a powerful reaction. Among those that Mr. Miyagawa worked with were students who became well-known writers, including Sakyo Komatsu (1931-2011) and Kazumi Takahashi (1931-1971).

When Mr. Miyagawa reached retirement age and left Motomachi Senior High School at the age of 60, he joined the Hiroshima o Kataru Kai, a group that shared their experiences of the Hiroshima bombing, and began to relate his account to students on school trips. He also went to South Korea to lend his support to A-bomb survivors there. He said, “The A-bomb survivors in South Korea have been neglected and I want to help them.” He has made many visits to South Korea and worked hard to provide the survivors with medical support.

In mid-July, prior to the A-bomb anniversary on August 6, Mr. Miyagawa put his hands together in a prayer for peace at the A-bomb Monument of Hiroshima First Municipal Girls’ School, located at the foot of Peace Bridge. Before his death, Zoroku wrote in a record compiled by the school’s alumni association to remember the victims: “Whenever I go across Peace Bridge, I can still picture the students and my heart aches with sorrow.” Mr. Miyagawa, who is now 88 years old, said, “What would be best is a peaceful world where everyone can live safely each day. The loss of human life in war must never be repeated.” This is his fervent desire.

Teenagers’ impressions

Shocked by survivor’s guilt

The parents of his father’s students complained bitterly, “All of your family members have survived. Give us back our daughter.” Mr. Miyagawa said in a pained voice, “I felt more sorry than lucky that my family had escaped injury.” I was shocked by his words. The atomic bombing even made him feel guilty for having survived. I’m sure there are many people who still have invisible wounds from the war. I want to meet more of them in the future and learn from them. (Akane Sato, 15)

Learning about A-bomb survivors in South Korea

Mr. Miyagawa has worked with others to lend support to A-bomb survivors in South Korea for many years. There isn’t a lot of interest in A-bomb survivors in South Korea, and there was no support system for these people. I realized that there’s a gap between South Korea and Hiroshima in this way, because in Hiroshima, A-bomb survivors share their experiences and it’s common for schools to have a peace studies program. I had known that there were A-bomb survivors living in other countries, but this was the first time I learned about the large gap in support. I want to broaden my perspective and learn more about the A-bomb survivors in South Korea. (Miki Meguro, 15)

(Originally published on August 6, 2018)