Survivors’ Stories: Yoshinori Kato, 90, Hiroshima: Unable to save the lives of children

Oct. 1, 2018

by Yuji Yamamoto, Staff Writer

These words run repeatedly through the mind of Yoshinori Kato, 90: “I’m sorry I couldn’t save you.” On the day the city of Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb, Mr. Kato, who was 17, tried desperately to rescue children who were trapped under the collapsed building of Danbara National School (now Danbara Elementary School located in Minami Ward). However, he had no choice but to leave the children behind as raging flames closed in.

Back then, Mr. Kato was a first-year student at the Hiroshima Technical Institute (now Hiroshima University). But classes were not being held because of the war; instead, he was mobilized to work at the Kure Naval Arsenal, an assignment that lasted until July 1945. Because of air raids on the city of Kure, he was ordered to return to his home in Hiroshima. His father had died of illness two years before and, to seeking a safer location, his mother and three brothers had moved to her parents’ house in the village of Tabusa (now Shobara) in the northern part of the prefecture. Mr. Kato was living in Hiroshima with his aunt and uncle.

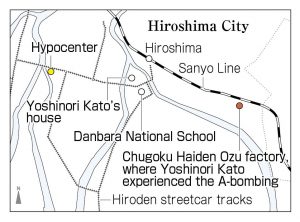

The first class since his enrollment in the school had been planned for August 6. Mr. Kato, along with his classmates, went to the Ozu factory of Chugoku Hayden (now the Chugoku Electric Power Company), which was located about 3.4 kilometers from the hypocenter. He felt excited about finally getting down to academic work. But when his physics class began, there was an intense flash, immediately followed by the ceiling collapsing. Then there was darkness.

After they made sure that everyone was all right, they went out of the building and were startled by what they saw. There was a huge mushroom cloud rising in the blue sky. Mr. Kato and his friends began walking toward his house in the Kyobashi-cho district in present-day Minami Ward. They came across many survivors whose faces were bloated and were nearly naked. He asked them what had happened, but no one really knew.

Fire was blazing so fiercely around his house that he could not approach it. Suddenly, a man grasped him by the hand. It turned out to be a teacher from Danbara National School. When Mr. Kato reached the school, he saw seven or eight children trapped under the collapsed school building. There were flames right above them.

Mr. Kato and his friends tried to pull them out, but they cried out in pain because their bodies were wedged inside the wreckage. He told them to hold on. He and his friends didn’t want to give up, but the fire was merciless. In the end, he gave some water to a girl then had to leave her. They were able to save only one child. When they arrived at the East Drill Ground, they were in a complete daze.

Before dusk fell, he began walking toward his house through a garden called Sentei (now known as Shukkeien Garden). It felt like an experience of hell. There were countless bodies, their heads in the pond. He followed the river, which had little water in it until the Kyobashi Bridge, and there he came across his aunt.

The next day, he went to the Hiroshima Post Office, where his uncle worked, but was unable to find any trace of him among the charred ruins of the building. His aunt wanted to continue searching for him, but Mr. Kato persuaded her that they should go to where his mother was. They walked to Kumura Station, on the Geibi Line, and were finally able to board a train on August 8.

Toward the end of September, his hair fell out in clumps and he thought that he would soon be dead. He was prepared to accept his fate. But his hair began to grow back at the beginning of the following year and he regained the strength to go on living.

After the war, Mr. Kato got a job at the Chugoku Electric Power Company. At the age of 27, he came down with tuberculosis and was admitted to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, where he met Sadako Sasaki. Sadako called him “Big Brother.” After Mr. Kato was discharged from the hospital, Sadako succumbed to leukemia.

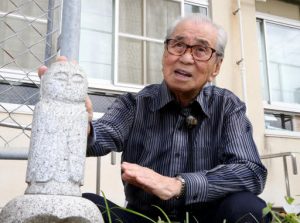

Thinking that he should tell people what happened to the students at Danbara National School, Mr. Kato drew pictures of them based on his memories. Around 30 years after the atomic bombing, he began offering a prayer at the elementary school on August 6, though he did not tell anyone about it. Half a century after the bombing, he sent a letter to the school, describing his experience, then started sharing his account with the students there. To remember the victims, he donated a statue of Jizo, the guardian of children, and had it placed at the site where he could not save their lives.

Due to his advancing age, this year he had to stop speaking to students about his experience. But he believes that if children pass on his account to the generations that follow, the victims will be pleased. He placed his hands together, praying for a world where no more lives will come to such a sad end.

Teenagers’ Impressions

War makes people suffer, over and over again

If I were Mr. Kato, I would have experienced so much suffering. The first suffering was when he couldn’t study because he had to work as a mobilized student. I might just think I was lucky that I didn’t have to study. But Mr. Kato entered the school because he wanted to study, so I guess it was hard for him. The second suffering was when he couldn’t save the lives of those children. It would have had a lasting impact on me if I had to abandon that girl. It is war itself that makes people experience anguish, over and over again. (Atsuhito Ito, 15)

Threat of nuclear weapons not someone else’s problem

Mr. Kato stressed that he wanted young people to take more interest in nuclear weapons and the atomic bombings. Because he experienced the atomic bombing as a teenager and has a clear memory of that terrible event, I guess he knows that the current conditions involving nuclear weapons are dangerous. I have come to realize that this is not somebody else’s problem. I have to come up with what I can do for my future children and grandchildren. (Hisashi Iwata, 17)

(Originally published on October 1, 2018)

These words run repeatedly through the mind of Yoshinori Kato, 90: “I’m sorry I couldn’t save you.” On the day the city of Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb, Mr. Kato, who was 17, tried desperately to rescue children who were trapped under the collapsed building of Danbara National School (now Danbara Elementary School located in Minami Ward). However, he had no choice but to leave the children behind as raging flames closed in.

Back then, Mr. Kato was a first-year student at the Hiroshima Technical Institute (now Hiroshima University). But classes were not being held because of the war; instead, he was mobilized to work at the Kure Naval Arsenal, an assignment that lasted until July 1945. Because of air raids on the city of Kure, he was ordered to return to his home in Hiroshima. His father had died of illness two years before and, to seeking a safer location, his mother and three brothers had moved to her parents’ house in the village of Tabusa (now Shobara) in the northern part of the prefecture. Mr. Kato was living in Hiroshima with his aunt and uncle.

The first class since his enrollment in the school had been planned for August 6. Mr. Kato, along with his classmates, went to the Ozu factory of Chugoku Hayden (now the Chugoku Electric Power Company), which was located about 3.4 kilometers from the hypocenter. He felt excited about finally getting down to academic work. But when his physics class began, there was an intense flash, immediately followed by the ceiling collapsing. Then there was darkness.

After they made sure that everyone was all right, they went out of the building and were startled by what they saw. There was a huge mushroom cloud rising in the blue sky. Mr. Kato and his friends began walking toward his house in the Kyobashi-cho district in present-day Minami Ward. They came across many survivors whose faces were bloated and were nearly naked. He asked them what had happened, but no one really knew.

Fire was blazing so fiercely around his house that he could not approach it. Suddenly, a man grasped him by the hand. It turned out to be a teacher from Danbara National School. When Mr. Kato reached the school, he saw seven or eight children trapped under the collapsed school building. There were flames right above them.

Mr. Kato and his friends tried to pull them out, but they cried out in pain because their bodies were wedged inside the wreckage. He told them to hold on. He and his friends didn’t want to give up, but the fire was merciless. In the end, he gave some water to a girl then had to leave her. They were able to save only one child. When they arrived at the East Drill Ground, they were in a complete daze.

Before dusk fell, he began walking toward his house through a garden called Sentei (now known as Shukkeien Garden). It felt like an experience of hell. There were countless bodies, their heads in the pond. He followed the river, which had little water in it until the Kyobashi Bridge, and there he came across his aunt.

The next day, he went to the Hiroshima Post Office, where his uncle worked, but was unable to find any trace of him among the charred ruins of the building. His aunt wanted to continue searching for him, but Mr. Kato persuaded her that they should go to where his mother was. They walked to Kumura Station, on the Geibi Line, and were finally able to board a train on August 8.

Toward the end of September, his hair fell out in clumps and he thought that he would soon be dead. He was prepared to accept his fate. But his hair began to grow back at the beginning of the following year and he regained the strength to go on living.

After the war, Mr. Kato got a job at the Chugoku Electric Power Company. At the age of 27, he came down with tuberculosis and was admitted to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital, where he met Sadako Sasaki. Sadako called him “Big Brother.” After Mr. Kato was discharged from the hospital, Sadako succumbed to leukemia.

Thinking that he should tell people what happened to the students at Danbara National School, Mr. Kato drew pictures of them based on his memories. Around 30 years after the atomic bombing, he began offering a prayer at the elementary school on August 6, though he did not tell anyone about it. Half a century after the bombing, he sent a letter to the school, describing his experience, then started sharing his account with the students there. To remember the victims, he donated a statue of Jizo, the guardian of children, and had it placed at the site where he could not save their lives.

Due to his advancing age, this year he had to stop speaking to students about his experience. But he believes that if children pass on his account to the generations that follow, the victims will be pleased. He placed his hands together, praying for a world where no more lives will come to such a sad end.

Teenagers’ Impressions

War makes people suffer, over and over again

If I were Mr. Kato, I would have experienced so much suffering. The first suffering was when he couldn’t study because he had to work as a mobilized student. I might just think I was lucky that I didn’t have to study. But Mr. Kato entered the school because he wanted to study, so I guess it was hard for him. The second suffering was when he couldn’t save the lives of those children. It would have had a lasting impact on me if I had to abandon that girl. It is war itself that makes people experience anguish, over and over again. (Atsuhito Ito, 15)

Threat of nuclear weapons not someone else’s problem

Mr. Kato stressed that he wanted young people to take more interest in nuclear weapons and the atomic bombings. Because he experienced the atomic bombing as a teenager and has a clear memory of that terrible event, I guess he knows that the current conditions involving nuclear weapons are dangerous. I have come to realize that this is not somebody else’s problem. I have to come up with what I can do for my future children and grandchildren. (Hisashi Iwata, 17)

(Originally published on October 1, 2018)