20 years since India and Pakistan performed their first nuclear tests

Oct. 22, 2018

by Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer

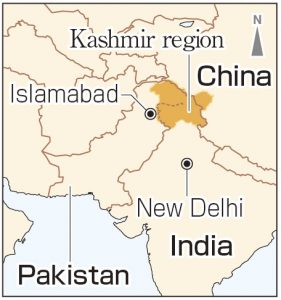

Twenty years have passed since India and Pakistan performed their first nuclear tests in 1998. Both nations, non-members of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), have since pressed on with their nuclear development efforts through these two decades, greatly increasing the number of nuclear weapons that they possess. These two nuclear states have had a fractious relationship for more than 70 years, particularly concerning the issue of territorial rights over the Kashmir region, and the danger remains that they may resort to the use of nuclear arms. However, attention on nuclear issues in South Asia, including the interest of people in the A-bombed cities, has declined in comparison with North Korea, which has drawn greater focus.

Haruko Moritaki, 79, a resident of Saeki Ward, is an organizer and the head of a citizens’ group that promotes peace exchanges between young people in India and Pakistan. Against the backdrop of the nuclear testing duel between these two countries, the group invited young people from India and Pakistan to visit Hiroshima on five occasions between 2000 and 2007 to promote mutual understanding in the A-bombed city.

For one of these youth, the visit to Hiroshima was a turning point. He went on to become a photojournalist, paying another visit to Hiroshima and, through his work, conveying the damage that radiation exposure from the uranium mines in India has caused. However, the program extending invitations to young people from India and Pakistan was discontinued in 2008 due to a lack of funds and less volatile conditions in South Asia. Ms. Moritaki has continued to address the nuclear problem in that part of the world by holding the World Nuclear Victims Forum in Hiroshima, but is concerned that, “We have to nurture young people to carry on with efforts to curtail nuclear development activities.”

Amid these circumstances, there are new efforts being made in both India and Pakistan. Fauzia Minallah, 55, a Pakistani artist, has been working with ANT-Hiroshima, a non-profit organization in Hiroshima, on an animated film about Sadako Sasaki, a young Japanese girl who died of A-bomb-induced leukemia 10 years after she was exposed to radiation in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

The story involves a magical bird that carries two children around the world and introduces them to Sadako, who persisted in folding paper cranes from her desire to live, and the reconstruction of Hiroshima after the devastation wrought by the atomic bombing. The story encourages viewers to consider what actions should be taken to make a more peaceful world.

Animated film about the life of Sadako Sasaki

“I want children to know how terrible radiation is,” said Tomoko Watanabe, 64, the executive director of ANT-Hiroshima. Ms. Watanabe met Ms. Minallah when she visited Pakistan as a member of the Hiroshima World Peace Mission (sponsored by the Hiroshima International Cultural Foundation) in 2005. In 2006, they collaborated on the making of a picture book about Sadako, which was used as the basis for the animated film. The English version of the film has just been completed and there are plans to create other language versions, too, including Urdu, a language used in Pakistan, and Dari and Pashto, which are spoken in Afghanistan, Pakistan’s neighbor. Ms. Minallah said, “It makes me sad because both countries have a lot of people living in poverty and instead of spending money on health care and education, that money goes into developing nuclear weapons.”

Picture book becomes a play in India

Meanwhile, a new attempt to convey the damage caused by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima has begun in India. A picture book titled Sagashiteimasu (Searching), by Arthur Binard, features the belongings of A-bomb victims and was translated into Hindi two years ago by Tomoko Kikuchi, 48, a Japanese translator from the city of Fukushima who now lives in India. The Abhigyan Natya Association, a theater company, was moved by the book and is now preparing to dramatize the story.

Ms. Kikuchi assists the members of the theater company by providing explanations about the atomic bombing. They plan to perform the play next March with the support of the Japan Foundation. They also hope to perform the play at schools with the wish that people who see it will reflect on the owners of the artifacts and recognize that a nuclear weapon stole away their precious lives.

Kumar Sundaram, 38, is an antinuclear campaigner based in India. He said, “I think the biggest problem in South Asia is that the common people don’t understand what the consequences of nuclear weapons are.” He believes that “The stories of the A-bomb survivors can play a game-changing role.” Unfortunately, it’s hard to say that the cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki are currently lending enough support to Mr. Sundaram’s efforts.

India and Pakistan have strengthened their nuclear capabilities

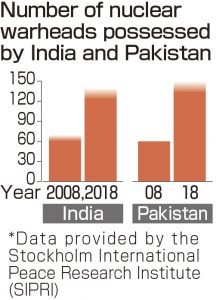

The dangers of “limited nuclear war” between India and Pakistan have been emphasized. The number of nuclear weapons held by these two nations has doubled over the past 10 years. According to an estimate made by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), as of January 2018, India holds 130 to 140 nuclear warheads while Pakistan holds 140 to 150. (In 2008, India had about 60 to 70 nuclear warheads and Pakistan had about 60.)

The two countries became separate and independent nations when British colonial rule ended in 1947. But just two months after gaining their independence, the first war between India and Pakistan broke out over territorial rights to the Kashmir region. To date, they have waged three wars against one another. India began its nuclear development program to counter not only Pakistan but also China. In 1962, India was defeated in the Sino-Indian Border Conflict. Two years after this war China carried out a successful nuclear test. India then conducted its first nuclear test in 1974. Pakistan launched its nuclear development efforts as a countermeasure against nuclear-armed India.

Having refused to join the NPT and turning their backs on the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which was adopted by the United Nations in 1996, both India and Pakistan carried out nuclear tests in May of 1998. Although the United States imposed economic sanctions on the two countries, these were lifted after the 9-11 terrorist attacks on the pretext of gaining their cooperation in the fight against terrorism. It seems that the United States has come to tacitly approve their nuclear arsenals.

Furthermore, the United States signed a civil nuclear cooperation agreement with India in 2008. Japan followed in U.S. footsteps by concluding a nuclear energy agreement with India in 2016, making it possible to export nuclear power technology to this huge market. Because cooperation with a non-signatory of the NPT, even in the area of nuclear energy technology, is a violation of the treaty’s fundamental rules, the United States and Japan have come under criticism for “treating India as an exception” and undermining the NPT regime. In Hiroshima, the Japan-India nuclear deal has stirred a backlash against the Japanese government. Such criticism includes sentiments like “This is tantamount to endorsement of nuclear-armed states by the A-bombed nation” and “The Japanese government has trampled on the feelings of the A-bombed city.”

Yasuhito Fukui, an associate professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute at Hiroshima City University and a specialist in nuclear disarmament under international law, was serving in the Arms Control and Disarmament Division of the Foreign Ministry at the time India and Pakistan performed nuclear tests in 1998. Because these two countries are non-signatories to the NPT, Professor Fukui believes that the lack of legal restrictions on their nuclear ambitions has led to the growth of their nuclear arsenals. They are able to beef up their nuclear forces but simply do this without stating it openly as policy. While the international community must be careful not to exacerbate their strained relations over Kashmir, Professor Fukui said, “I would like the Japanese government to reach out to both countries so that high-level officials and their citizens will visit Hiroshima to see the remnants of the atomic bombing and realize what could happen in their nations if a nuclear bomb exploded.”

(Originally published on October 22, 2018)

Twenty years have passed since India and Pakistan performed their first nuclear tests in 1998. Both nations, non-members of the Nuclear Non-proliferation Treaty (NPT), have since pressed on with their nuclear development efforts through these two decades, greatly increasing the number of nuclear weapons that they possess. These two nuclear states have had a fractious relationship for more than 70 years, particularly concerning the issue of territorial rights over the Kashmir region, and the danger remains that they may resort to the use of nuclear arms. However, attention on nuclear issues in South Asia, including the interest of people in the A-bombed cities, has declined in comparison with North Korea, which has drawn greater focus.

Haruko Moritaki, 79, a resident of Saeki Ward, is an organizer and the head of a citizens’ group that promotes peace exchanges between young people in India and Pakistan. Against the backdrop of the nuclear testing duel between these two countries, the group invited young people from India and Pakistan to visit Hiroshima on five occasions between 2000 and 2007 to promote mutual understanding in the A-bombed city.

For one of these youth, the visit to Hiroshima was a turning point. He went on to become a photojournalist, paying another visit to Hiroshima and, through his work, conveying the damage that radiation exposure from the uranium mines in India has caused. However, the program extending invitations to young people from India and Pakistan was discontinued in 2008 due to a lack of funds and less volatile conditions in South Asia. Ms. Moritaki has continued to address the nuclear problem in that part of the world by holding the World Nuclear Victims Forum in Hiroshima, but is concerned that, “We have to nurture young people to carry on with efforts to curtail nuclear development activities.”

Amid these circumstances, there are new efforts being made in both India and Pakistan. Fauzia Minallah, 55, a Pakistani artist, has been working with ANT-Hiroshima, a non-profit organization in Hiroshima, on an animated film about Sadako Sasaki, a young Japanese girl who died of A-bomb-induced leukemia 10 years after she was exposed to radiation in the atomic bombing of Hiroshima.

The story involves a magical bird that carries two children around the world and introduces them to Sadako, who persisted in folding paper cranes from her desire to live, and the reconstruction of Hiroshima after the devastation wrought by the atomic bombing. The story encourages viewers to consider what actions should be taken to make a more peaceful world.

Animated film about the life of Sadako Sasaki

“I want children to know how terrible radiation is,” said Tomoko Watanabe, 64, the executive director of ANT-Hiroshima. Ms. Watanabe met Ms. Minallah when she visited Pakistan as a member of the Hiroshima World Peace Mission (sponsored by the Hiroshima International Cultural Foundation) in 2005. In 2006, they collaborated on the making of a picture book about Sadako, which was used as the basis for the animated film. The English version of the film has just been completed and there are plans to create other language versions, too, including Urdu, a language used in Pakistan, and Dari and Pashto, which are spoken in Afghanistan, Pakistan’s neighbor. Ms. Minallah said, “It makes me sad because both countries have a lot of people living in poverty and instead of spending money on health care and education, that money goes into developing nuclear weapons.”

Picture book becomes a play in India

Meanwhile, a new attempt to convey the damage caused by the atomic bombing of Hiroshima has begun in India. A picture book titled Sagashiteimasu (Searching), by Arthur Binard, features the belongings of A-bomb victims and was translated into Hindi two years ago by Tomoko Kikuchi, 48, a Japanese translator from the city of Fukushima who now lives in India. The Abhigyan Natya Association, a theater company, was moved by the book and is now preparing to dramatize the story.

Ms. Kikuchi assists the members of the theater company by providing explanations about the atomic bombing. They plan to perform the play next March with the support of the Japan Foundation. They also hope to perform the play at schools with the wish that people who see it will reflect on the owners of the artifacts and recognize that a nuclear weapon stole away their precious lives.

Kumar Sundaram, 38, is an antinuclear campaigner based in India. He said, “I think the biggest problem in South Asia is that the common people don’t understand what the consequences of nuclear weapons are.” He believes that “The stories of the A-bomb survivors can play a game-changing role.” Unfortunately, it’s hard to say that the cities Hiroshima and Nagasaki are currently lending enough support to Mr. Sundaram’s efforts.

India and Pakistan have strengthened their nuclear capabilities

The dangers of “limited nuclear war” between India and Pakistan have been emphasized. The number of nuclear weapons held by these two nations has doubled over the past 10 years. According to an estimate made by the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), as of January 2018, India holds 130 to 140 nuclear warheads while Pakistan holds 140 to 150. (In 2008, India had about 60 to 70 nuclear warheads and Pakistan had about 60.)

The two countries became separate and independent nations when British colonial rule ended in 1947. But just two months after gaining their independence, the first war between India and Pakistan broke out over territorial rights to the Kashmir region. To date, they have waged three wars against one another. India began its nuclear development program to counter not only Pakistan but also China. In 1962, India was defeated in the Sino-Indian Border Conflict. Two years after this war China carried out a successful nuclear test. India then conducted its first nuclear test in 1974. Pakistan launched its nuclear development efforts as a countermeasure against nuclear-armed India.

Having refused to join the NPT and turning their backs on the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), which was adopted by the United Nations in 1996, both India and Pakistan carried out nuclear tests in May of 1998. Although the United States imposed economic sanctions on the two countries, these were lifted after the 9-11 terrorist attacks on the pretext of gaining their cooperation in the fight against terrorism. It seems that the United States has come to tacitly approve their nuclear arsenals.

Furthermore, the United States signed a civil nuclear cooperation agreement with India in 2008. Japan followed in U.S. footsteps by concluding a nuclear energy agreement with India in 2016, making it possible to export nuclear power technology to this huge market. Because cooperation with a non-signatory of the NPT, even in the area of nuclear energy technology, is a violation of the treaty’s fundamental rules, the United States and Japan have come under criticism for “treating India as an exception” and undermining the NPT regime. In Hiroshima, the Japan-India nuclear deal has stirred a backlash against the Japanese government. Such criticism includes sentiments like “This is tantamount to endorsement of nuclear-armed states by the A-bombed nation” and “The Japanese government has trampled on the feelings of the A-bombed city.”

Yasuhito Fukui, an associate professor at the Hiroshima Peace Institute at Hiroshima City University and a specialist in nuclear disarmament under international law, was serving in the Arms Control and Disarmament Division of the Foreign Ministry at the time India and Pakistan performed nuclear tests in 1998. Because these two countries are non-signatories to the NPT, Professor Fukui believes that the lack of legal restrictions on their nuclear ambitions has led to the growth of their nuclear arsenals. They are able to beef up their nuclear forces but simply do this without stating it openly as policy. While the international community must be careful not to exacerbate their strained relations over Kashmir, Professor Fukui said, “I would like the Japanese government to reach out to both countries so that high-level officials and their citizens will visit Hiroshima to see the remnants of the atomic bombing and realize what could happen in their nations if a nuclear bomb exploded.”

(Originally published on October 22, 2018)