Survivors’ Stories: Mineko Yonezawa, 86, Hiroshima: Living with fragments of glass in her body

Nov. 5, 2018

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

“These pieces of glass are reminders of my experience of the atomic bombing. I will take them into the next world with me,” said Mineko Yonezawa (nee Yamanaka), 86. Fragments of broken glass that flew through the air when the bomb exploded are still lodged in her right arm. The pieces of glass, which Ms. Yonezawa has lived with in her body since the age of 13, penetrated deeply and muscle then developed around them.

Ms. Yonezawa went to live in Manchuria (in northeastern China) when Kiyoshi, her father, was sent there for a new post with the Japanese army. In 1943, the family returned to Hiroshima from Manchuria and Ms. Yonezawa entered Yasuda Girls’ High School the next spring. However, she has little memory of studying there. Along with other second-year students, she was mobilized to work at the Homare aircraft factory in Kusunoki-cho, Nishi Ward, from August 1, 1945.

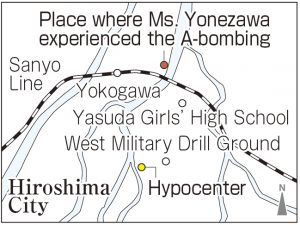

Female students were assigned to sharpen aluminum bars at the factory. On the morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Yonezawa left home for this assigned workplace wearing the usual white headband on her head. After the morning assembly at 8 a.m., she returned to her lathe station. The instant she sat down, the red-brick wall behind her collapsed with a clatter, and fragments of shattered glass were hurled through the air, piercing the right side of her body.

She was about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. Strewn with rubble, she crawled frantically from the wreckage, as if moving toward a light at the end of a tunnel. She saw people whose skin was dangling down from their arms, and soldiers whose hair had disappeared except for the part that had been covered by their cap.

Without knowing what was going on, she headed north along the Otagawa River and came to Oshiba Park. While seated in the park, a woman covered in blood suddenly ran about while crying out in a shrill, eerie voice, then fell flat to the ground. A little boy who was crying went to her and clung onto her, but she shook him off and began running again. “I think she was his mother. It was hell on earth.”

She managed to make it to a national school in Furuichi (now part of Asaminami Ward) and spent the night there. The next day, the father of one of Ms. Yonezawa’s friends took her home to Uchikoshi-cho (now part of Nishi Ward). Until the moment they saw their daughter, Ms. Yonezawa’s parents had been preparing themselves for her death. In notes written by Kiyoshi, who died in 1993, he said that he searched for his daughter with a “hekohimo” (a soft thin cloth like a waistband) so he could carry her body on his back.

Yasuda Girls’ High School lost a total of 315 students and 13 teachers in the A-bomb attack. Among those killed included the first-year students who were helping to tear down buildings in the city center to create a fire lane and 20 schoolmates who were mobilized to the Homare aircraft factory. “What would have happened if the bomb had exploded when we were having our morning assembly?” Ms. Yonezawa wonders. It was a twist of fate that, for her, spelled the difference between life and death.

The students faced hardships after the war as well. Their school building, which was in Nishihakushima-cho (now part of Naka Ward) and was located 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter, was demolished. When the decision was made to move the school to the former military barracks for the army corps of engineers, which was nearby, the students were mobilized to help clean up the wreckage. “All of us were terrified when the skeleton of a soldier was found beneath a wall that had collapsed,” Ms. Yonezawa recalled.

Ms. Yonezawa’s parents renovated their tilting home and opened a Japanese-style inn called “Marunaka Ryokan” and accepted demobilized soldiers. In 1952, film director Kaneto Shindo shot the movie “Children of the Atomic Bomb,” a masterpiece that told the world about the tragedy of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. During that time, the film crew stayed at her parents’ inn.

Nobuko Otowa played the leading role of a teacher who survived the atomic bombing and paid visits to her former kindergarten pupils, who were also survivors of the attack, several years later. While talking with a friend, the main character touched her right arm and said that she would like to keep the pieces of glass still embedded in her body in order to “remember August 6.” Mr. Shindo based that line on a conversation he had with Ms. Yonezawa.

She and her husband Minoru, 91, who is also an A-bomb survivor, took over her parents’ business, but they closed down the ryokan in 1994. Their eldest daughter and her Guatemalan husband now run a restaurant from their home which serves okonomiyaki, a “soul food” in Hiroshima (a kind of Japanese crepe made with pork and cabbage). People from various countries come to the restaurant and different languages, like English and Spanish, can be heard. Ms. Yonezawa said, “I hope the people of the world can speak together freely, like they do at the okonomiyaki shop, and help one another instead of feeling animosity.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

We have to fulfill Ms. Yonezawa’s wish

Ms. Yonezawa showed us her arm, which still has fragments of glass. I thought that the glass had a quiet but bold presence inside her arm. “I won’t remove the glass,” she told us. From her words, I felt her determination not to forget what happened that day. I feel strongly that we have to fulfill Ms. Yonezawa’s wish: “Do not hate each other. Make a peaceful world.” (Kotoori Kawagishi, 16)

I will treasure the happiness I already have

Back then, Ms. Yonezawa was a student, like us, but she worked at the factory every day, a hairband on her head. She had no chance to study or have fun. Many students died in the atomic bombing and even those that survived were forced to work hard to help build a new school building. The war deprived the students of their adolescence. While enduring a terrible time, she found ways to look for small rays of hope and happiness in her life. I learned the importance of treasuring the happiness I already have. (Yukiho Saito, 16)

(Originally published on November 5, 2018)

“These pieces of glass are reminders of my experience of the atomic bombing. I will take them into the next world with me,” said Mineko Yonezawa (nee Yamanaka), 86. Fragments of broken glass that flew through the air when the bomb exploded are still lodged in her right arm. The pieces of glass, which Ms. Yonezawa has lived with in her body since the age of 13, penetrated deeply and muscle then developed around them.

Ms. Yonezawa went to live in Manchuria (in northeastern China) when Kiyoshi, her father, was sent there for a new post with the Japanese army. In 1943, the family returned to Hiroshima from Manchuria and Ms. Yonezawa entered Yasuda Girls’ High School the next spring. However, she has little memory of studying there. Along with other second-year students, she was mobilized to work at the Homare aircraft factory in Kusunoki-cho, Nishi Ward, from August 1, 1945.

Female students were assigned to sharpen aluminum bars at the factory. On the morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Yonezawa left home for this assigned workplace wearing the usual white headband on her head. After the morning assembly at 8 a.m., she returned to her lathe station. The instant she sat down, the red-brick wall behind her collapsed with a clatter, and fragments of shattered glass were hurled through the air, piercing the right side of her body.

She was about 1.8 kilometers from the hypocenter. Strewn with rubble, she crawled frantically from the wreckage, as if moving toward a light at the end of a tunnel. She saw people whose skin was dangling down from their arms, and soldiers whose hair had disappeared except for the part that had been covered by their cap.

Without knowing what was going on, she headed north along the Otagawa River and came to Oshiba Park. While seated in the park, a woman covered in blood suddenly ran about while crying out in a shrill, eerie voice, then fell flat to the ground. A little boy who was crying went to her and clung onto her, but she shook him off and began running again. “I think she was his mother. It was hell on earth.”

She managed to make it to a national school in Furuichi (now part of Asaminami Ward) and spent the night there. The next day, the father of one of Ms. Yonezawa’s friends took her home to Uchikoshi-cho (now part of Nishi Ward). Until the moment they saw their daughter, Ms. Yonezawa’s parents had been preparing themselves for her death. In notes written by Kiyoshi, who died in 1993, he said that he searched for his daughter with a “hekohimo” (a soft thin cloth like a waistband) so he could carry her body on his back.

Yasuda Girls’ High School lost a total of 315 students and 13 teachers in the A-bomb attack. Among those killed included the first-year students who were helping to tear down buildings in the city center to create a fire lane and 20 schoolmates who were mobilized to the Homare aircraft factory. “What would have happened if the bomb had exploded when we were having our morning assembly?” Ms. Yonezawa wonders. It was a twist of fate that, for her, spelled the difference between life and death.

The students faced hardships after the war as well. Their school building, which was in Nishihakushima-cho (now part of Naka Ward) and was located 1.4 kilometers from the hypocenter, was demolished. When the decision was made to move the school to the former military barracks for the army corps of engineers, which was nearby, the students were mobilized to help clean up the wreckage. “All of us were terrified when the skeleton of a soldier was found beneath a wall that had collapsed,” Ms. Yonezawa recalled.

Ms. Yonezawa’s parents renovated their tilting home and opened a Japanese-style inn called “Marunaka Ryokan” and accepted demobilized soldiers. In 1952, film director Kaneto Shindo shot the movie “Children of the Atomic Bomb,” a masterpiece that told the world about the tragedy of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima. During that time, the film crew stayed at her parents’ inn.

Nobuko Otowa played the leading role of a teacher who survived the atomic bombing and paid visits to her former kindergarten pupils, who were also survivors of the attack, several years later. While talking with a friend, the main character touched her right arm and said that she would like to keep the pieces of glass still embedded in her body in order to “remember August 6.” Mr. Shindo based that line on a conversation he had with Ms. Yonezawa.

She and her husband Minoru, 91, who is also an A-bomb survivor, took over her parents’ business, but they closed down the ryokan in 1994. Their eldest daughter and her Guatemalan husband now run a restaurant from their home which serves okonomiyaki, a “soul food” in Hiroshima (a kind of Japanese crepe made with pork and cabbage). People from various countries come to the restaurant and different languages, like English and Spanish, can be heard. Ms. Yonezawa said, “I hope the people of the world can speak together freely, like they do at the okonomiyaki shop, and help one another instead of feeling animosity.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

We have to fulfill Ms. Yonezawa’s wish

Ms. Yonezawa showed us her arm, which still has fragments of glass. I thought that the glass had a quiet but bold presence inside her arm. “I won’t remove the glass,” she told us. From her words, I felt her determination not to forget what happened that day. I feel strongly that we have to fulfill Ms. Yonezawa’s wish: “Do not hate each other. Make a peaceful world.” (Kotoori Kawagishi, 16)

I will treasure the happiness I already have

Back then, Ms. Yonezawa was a student, like us, but she worked at the factory every day, a hairband on her head. She had no chance to study or have fun. Many students died in the atomic bombing and even those that survived were forced to work hard to help build a new school building. The war deprived the students of their adolescence. While enduring a terrible time, she found ways to look for small rays of hope and happiness in her life. I learned the importance of treasuring the happiness I already have. (Yukiho Saito, 16)

(Originally published on November 5, 2018)