Marking the 100th year since the end of World War I, reflecting on the rise of weapons of mass destruction

Nov. 13, 2018

Email interview with Dr. Dominiek Dendooven, researcher and curator at the In Flanders Fields Museum

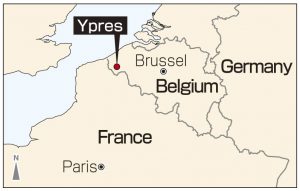

From Ypres, Belgium, the first city attacked by chemical weapons, to Hiroshima, the A-bombed city

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

On November 11, a memorial event was held in Europe to mark the centenary of the end of the First World War (1914-1918). Heads of state and government took part in the ceremony at an old battleground of the war. However, not many people talk about the fact that the war, which took the lives of over 10 million people, marked the beginning of a new era of weapons of mass destruction, including atomic bombs. The Chugoku Shimbun asked Dr. Dominiek Dendooven, 47, a researcher and curator at the In Flanders Fields Museum, about the first use of chemical weapons in Ypres, Belgium, and the nature of the war. These are excerpts from that interview, conducted via email.

Indiscriminate killing: no control over the scope and harm

The fighting in World War I is characterized by its industrial influence, and, as a consequence, the fact that mass killing became widespread. New technology, particularly advances in artillery, meant that such killing became a technical act, devoid of emotion. One artillery shell could easily dispatch more than 20 people, but the gunner was several kilometers behind the frontline and didn’t see the consequences of his act, and thus felt nothing.

As a result, casualties in the war were extensive, with over 10 million people becoming victims. At the small front in Belgium, an area of some 30 square kilometers, half a million people were killed over a period of four years. Of these, nearly half went “missing”: most of them were literally “blown to bits” by artillery.

The main military difficulty on the war’s western front was a stalemate. After September 1914 it was a war fought from the trenches where neither side could gain an advantage so new weapons and tactics were introduced as the combatants sought a breakthrough. On April 22, 1915, chlorine gas was used by the German army in Ypres. It was the first large-scale use of chemical weapons in human history.

However, some generals simply saw this attack as an experiment and there were not enough troops to exploit the situation, despite the fact that the gas had produced a large gap in the allied lines. Although other new types of gas, including phosgene and mustard gas, were also introduced, Germany was unable to win the war. While relatively few soldiers were killed outright by the gas—perhaps 1% of the war’s victims—many thousands were harmed, and that damage to their health often extended throughout their lives.

The First World War was arguably also the first total war, where entire societies, not only each nation’s military, were mobilized for the war effort. These belligerent societies became involved politically, economically (a war economy), and culturally (propaganda, the idea of the home front). Thus, the entire society of the enemy was seen as guilty, too, including civilians, and they were viewed as legitimate targets.

We can glean several lessons from this war. Most importantly, World War I broke out because of the lack of will to keep the peace. This is always dangerous. It shows how easily war can break out. And everyone expected that war to be brief. One never knows how a war will develop and how long it will last. It was begun, and mainly fought, by the great European powers of that time. The result, though, was that these great powers “disempowered” themselves: the German Empire lost the war, but France and the British Empire suffered significant losses as well.

I believe that some of the actions taken during World War I ultimately led to the level of mass destruction that was seen at the end of World War II. Gas was arguably the first weapon of mass destruction as it made no distinction between soldiers and civilians and, once released, the scope of its impact and the harm it could cause could not be controlled.

In Flanders Fields Museum is a very interactive museum which uses immersive techniques in addition to objects, photos, and films. The philosophy of our museum is to approach the war through personal stories. This makes it more a museum of war experiences than of warfare. By focusing on individual war experiences, we also overcome boundaries of nationality (British, German, Belgian), gender (man-woman), and status (military-civilian, officer-soldier, etc.). The landscape around Ypres still bears many scars from that war (cemeteries, trenches, bunkers), and now that the last direct witnesses have died, we consider the landscape to be the last witness.

Profile

Dr. Dominiek Dendooven

Born in Bruges, Belgium. Graduated from Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Earned a doctoral degree in history at the University of Kent and Universiteit Antwerpen. Joined In Flanders Fields Museum in 1997. After serving as an education officer, assumed his current position as a researcher and curator in 1998. Also teaches the history of the First World War at a local university.

Ypres, working with Hiroshima for nuclear abolition, holds A-bomb exhibition

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

The city of Ypres, Belgium, which suffered a large-scale chemical weapons attack for the first time in human history, is working with the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to advance the cause of nuclear abolition. In 1985, Ypres declared itself “a city of peace” and the mayor of Ypres now serves as a vice president of Mayors for Peace (for which Hiroshima Mayor Kazumi Matsui serves as president).

Strengthening its relationship with the A-bombed cities, Ypres opened the “Hiroshima-Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Exhibition” on November 9. The exhibition was planned alongside the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in conjunction with the centenary of the end of the First World War, hoping that it would become an opportunity to highlight the inhumane consequences of weapons of mass destruction.

About 20 A-bomb related items, including replicas of artifacts, and photos which show the devastation caused by the atomic bombs, will be on display until December 2. Sadae Kasaoka, 86, an A-bomb survivor who lost her parents in the Hiroshima bombing and now lives in Nishi Ward, will travel to Ypres to share her account at a museum and university there. She said she would like to stress to others that the weak and innocent, civilians such as children and the elderly, always suffer when war is waged.

One of the exhibits on display in Ypres is a lunchbox which once belonged to a first-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls' School (now Funairi High School). She was killed by the atomic bomb while working as a mobilized student. This month, second-year students at Funairi High School learned about World War I in world history class. Yuki Saeki, 31, a teacher at Funairi High School, said, “I would like the students to learn why the First World War occurred and how it led to the Second World War, as well as the tragedy of the atomic bombing.”

By looking at pictures of posters which inflamed citizens’ patriotism, gas masks, and tanks that made their first appearance in war, the students engaged in discussion in the class while using key phrases like “new weapon” and “total war.” Mana Fujioka, 16, said, “I learned that new weapons were developed one after another and that this eventually led to the atomic bomb. It is important to clearly understand world history in order to create a peaceful world.”

Keywords

World War I and chemical weapons

Chlorine gas used by the German army against French troops in Ypres, Belgium, is said to have killed approximately 5,000 people. Although the Hague Convention of 1899 prohibited the use of toxic weapons on the battlefields, it was not followed. France and the United Kingdom launched gas attacks in retaliation, but Germany developed new types of chemical weapons, one after another. Mustard gas, or yperite, one of the weapons developed by Germany, gave Ypres its name. The Geneva Protocol of 1925 again prohibited the use of gas, but its production remained uncontrolled.

During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Army pursued the production of chemical weapons on the island of Okunojima, in the city of Takehara, based on German technology.

(Originally published on November 13, 2018)

From Ypres, Belgium, the first city attacked by chemical weapons, to Hiroshima, the A-bombed city

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

On November 11, a memorial event was held in Europe to mark the centenary of the end of the First World War (1914-1918). Heads of state and government took part in the ceremony at an old battleground of the war. However, not many people talk about the fact that the war, which took the lives of over 10 million people, marked the beginning of a new era of weapons of mass destruction, including atomic bombs. The Chugoku Shimbun asked Dr. Dominiek Dendooven, 47, a researcher and curator at the In Flanders Fields Museum, about the first use of chemical weapons in Ypres, Belgium, and the nature of the war. These are excerpts from that interview, conducted via email.

Indiscriminate killing: no control over the scope and harm

The fighting in World War I is characterized by its industrial influence, and, as a consequence, the fact that mass killing became widespread. New technology, particularly advances in artillery, meant that such killing became a technical act, devoid of emotion. One artillery shell could easily dispatch more than 20 people, but the gunner was several kilometers behind the frontline and didn’t see the consequences of his act, and thus felt nothing.

As a result, casualties in the war were extensive, with over 10 million people becoming victims. At the small front in Belgium, an area of some 30 square kilometers, half a million people were killed over a period of four years. Of these, nearly half went “missing”: most of them were literally “blown to bits” by artillery.

The main military difficulty on the war’s western front was a stalemate. After September 1914 it was a war fought from the trenches where neither side could gain an advantage so new weapons and tactics were introduced as the combatants sought a breakthrough. On April 22, 1915, chlorine gas was used by the German army in Ypres. It was the first large-scale use of chemical weapons in human history.

However, some generals simply saw this attack as an experiment and there were not enough troops to exploit the situation, despite the fact that the gas had produced a large gap in the allied lines. Although other new types of gas, including phosgene and mustard gas, were also introduced, Germany was unable to win the war. While relatively few soldiers were killed outright by the gas—perhaps 1% of the war’s victims—many thousands were harmed, and that damage to their health often extended throughout their lives.

The First World War was arguably also the first total war, where entire societies, not only each nation’s military, were mobilized for the war effort. These belligerent societies became involved politically, economically (a war economy), and culturally (propaganda, the idea of the home front). Thus, the entire society of the enemy was seen as guilty, too, including civilians, and they were viewed as legitimate targets.

We can glean several lessons from this war. Most importantly, World War I broke out because of the lack of will to keep the peace. This is always dangerous. It shows how easily war can break out. And everyone expected that war to be brief. One never knows how a war will develop and how long it will last. It was begun, and mainly fought, by the great European powers of that time. The result, though, was that these great powers “disempowered” themselves: the German Empire lost the war, but France and the British Empire suffered significant losses as well.

I believe that some of the actions taken during World War I ultimately led to the level of mass destruction that was seen at the end of World War II. Gas was arguably the first weapon of mass destruction as it made no distinction between soldiers and civilians and, once released, the scope of its impact and the harm it could cause could not be controlled.

In Flanders Fields Museum is a very interactive museum which uses immersive techniques in addition to objects, photos, and films. The philosophy of our museum is to approach the war through personal stories. This makes it more a museum of war experiences than of warfare. By focusing on individual war experiences, we also overcome boundaries of nationality (British, German, Belgian), gender (man-woman), and status (military-civilian, officer-soldier, etc.). The landscape around Ypres still bears many scars from that war (cemeteries, trenches, bunkers), and now that the last direct witnesses have died, we consider the landscape to be the last witness.

Profile

Dr. Dominiek Dendooven

Born in Bruges, Belgium. Graduated from Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Earned a doctoral degree in history at the University of Kent and Universiteit Antwerpen. Joined In Flanders Fields Museum in 1997. After serving as an education officer, assumed his current position as a researcher and curator in 1998. Also teaches the history of the First World War at a local university.

Ypres, working with Hiroshima for nuclear abolition, holds A-bomb exhibition

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

The city of Ypres, Belgium, which suffered a large-scale chemical weapons attack for the first time in human history, is working with the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to advance the cause of nuclear abolition. In 1985, Ypres declared itself “a city of peace” and the mayor of Ypres now serves as a vice president of Mayors for Peace (for which Hiroshima Mayor Kazumi Matsui serves as president).

Strengthening its relationship with the A-bombed cities, Ypres opened the “Hiroshima-Nagasaki Atomic Bomb Exhibition” on November 9. The exhibition was planned alongside the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in conjunction with the centenary of the end of the First World War, hoping that it would become an opportunity to highlight the inhumane consequences of weapons of mass destruction.

About 20 A-bomb related items, including replicas of artifacts, and photos which show the devastation caused by the atomic bombs, will be on display until December 2. Sadae Kasaoka, 86, an A-bomb survivor who lost her parents in the Hiroshima bombing and now lives in Nishi Ward, will travel to Ypres to share her account at a museum and university there. She said she would like to stress to others that the weak and innocent, civilians such as children and the elderly, always suffer when war is waged.

One of the exhibits on display in Ypres is a lunchbox which once belonged to a first-year student at Hiroshima First Municipal Girls' School (now Funairi High School). She was killed by the atomic bomb while working as a mobilized student. This month, second-year students at Funairi High School learned about World War I in world history class. Yuki Saeki, 31, a teacher at Funairi High School, said, “I would like the students to learn why the First World War occurred and how it led to the Second World War, as well as the tragedy of the atomic bombing.”

By looking at pictures of posters which inflamed citizens’ patriotism, gas masks, and tanks that made their first appearance in war, the students engaged in discussion in the class while using key phrases like “new weapon” and “total war.” Mana Fujioka, 16, said, “I learned that new weapons were developed one after another and that this eventually led to the atomic bomb. It is important to clearly understand world history in order to create a peaceful world.”

Keywords

World War I and chemical weapons

Chlorine gas used by the German army against French troops in Ypres, Belgium, is said to have killed approximately 5,000 people. Although the Hague Convention of 1899 prohibited the use of toxic weapons on the battlefields, it was not followed. France and the United Kingdom launched gas attacks in retaliation, but Germany developed new types of chemical weapons, one after another. Mustard gas, or yperite, one of the weapons developed by Germany, gave Ypres its name. The Geneva Protocol of 1925 again prohibited the use of gas, but its production remained uncontrolled.

During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Army pursued the production of chemical weapons on the island of Okunojima, in the city of Takehara, based on German technology.

(Originally published on November 13, 2018)