Building Bridges: Shamsul Hadi Shams, 34, Afghan training officer at the UNITAR Hiroshima Office

Jan. 28, 2019

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Power of Hiroshima’s revival is shared with people in conflict areas

Shamsul Hadi Shams, 34, a resident of Higashihiroshima who works for the Hiroshima Office of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), is making his presence felt in Hiroshima, more and more. Mr. Shams has spent over ten years in Hiroshima since leaving Afghanistan, his homeland, which still suffers from war and terrorist attacks.

Last December, 24 young people from Iraq came to the UNITAR Hiroshima Office, in Naka Ward, for a training program. The trainees, who were in their 20s and 30s, work for government institutions and universities in their nation. The training, marking its third year, is designed to develop local human resources who are able to contribute to advancing reconstruction in Iraq. Mr. Shams has been involved in this training program from the start. “Because the trainees are also from an area facing conflict, they feel that Hiroshima and its past is very important to them,” he explained. “They want to know a lot about Hiroshima. There is so much interest. When you suffer from war, you lose people, you lose family members. It’s so difficult to overcome these feelings of loss.” He added that despite the frustration and anger that people from countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, and South Sudan feel, they want to learn about Hiroshima, particularly the human side of how the people of Hiroshima have dealt with and overcome their own feelings of loss, anger, and sorrow.

Mr. Shams is also responsible for bringing in trainees from South Sudan, which is still plagued by civil war. He guides them around the Peace Memorial Park and the Peace Memorial Museum, and provides them with opportunities to interact with A-bomb survivors and second-generation survivors.

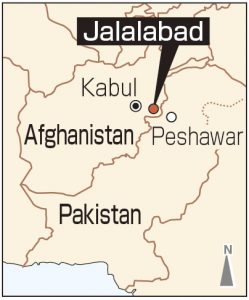

His career grew out of his own family’s hardships. As the eighth child of 11 children, he was born in Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, five years after his nation was invaded by the former Soviet Union. His father, who worked for the government and for a university, was kept under surveillance by the communist regime. His family then fled to a location near Peshawar, in northwest Pakistan, which borders Afghanistan.

Mr. Shams’s eldest brother, who had been studying at a university in Saudi Arabia, joined Afghan civilians, backed by the United States, to fight again the communist government. He lost his life in a bombing by the Soviet military in eastern Afghanistan. His body, which was burned severely and was missing a leg, was brought back to his family in Pakistan. Reflecting on that event, Mr. Shams said, “It was my eldest brother. He was educated, and very smart, so my parents were counting on him. He was the backbone of our family so losing him was a big loss. I had never seen my father cry before, but when my brother died, he was in tears. That meant it was a huge loss for the whole family.”

Growing up as a refugee, Mr. Shams went to college and graduate school in Pakistan. But his homeland devolved into fierce fighting again. This was the war in Afghanistan, led by the United States after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The war made it impossible for him to return to Afghanistan and live there, where a state of chaos ensued as a result of U.S. air strikes and terrorist attacks.

He came to Japan in 2007. With a scholarship from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, he entered the doctoral program in the Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation at Hiroshima University. Explaining why he chose to study in Hiroshima, Mr. Shams said that he had wondered what Hiroshima now looked like when he learned about the atomic bombing and the devastation of this nuclear attack when he was in high school in Pakistan. He added, “I was really inspired by the story of Hiroshima and I wanted to come here to study, to learn about what happened during the war, how it happened, and how the people of Hiroshima overcame this tragedy and their hardships.”

A week after arriving in Hiroshima, he saw the A-bomb Dome up close and was very moved by the experience. “My experience of that place was my inspiration,” he said. “I was so moved. For me, the A-bomb Dome is a time machine. When you look at it, it takes you right back to August 6, 1945. I can visualize the scenes of that time in my mind. Maybe it’s the combination of Afghanistan and Hiroshima. There’s a very close connection between the two.”

During his studies at the graduate school, he learned about reconstruction and conflict resolution, then received his Ph.D. He was hired by UNITAR in 2012.

The long war in Afghanistan still goes on, with U.S. forces stationed there under the current U.S. administration of President Donald Trump and Islamic extremists again gaining influence in the region. Peace talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban, the armed opposition group, have made only partial progress. In Jalalabad, the city in eastern Afghanistan where his parents’ home still stands, suicide bomb attacks are taking place with alarming frequency. Mr. Shams has been unable to return there as often as before.

“I always wanted to do work that could lend support to people affected by conflict, poverty, and a lack of security, such as my own nation Afghanistan as well as countries like Iraq and South Sudan. UNITAR Hiroshima is the best platform for me to do this work. In this way, I can create bridges between Hiroshima and all the countries I work with.” He went on, “I wanted to help spread Hiroshima’s message, which is the message of peace, resilience, and self-reliance. I feel eager and happy to share this message with others.”

Mr. Shams’s passion for this work, which led him to join UNITAR, can now be seen in his personal activities, too. He has translated a picture book about Sadako Sasaki into his native language for distribution back in Afghanistan. And with his Japanese wife and friends, whom he met during his time in Hiroshima, he plans to publish a picture book about Hiroshima’s A-bombed trees, which survived the tragic bombing, in Afghanistan this spring.

(Originally published on January 28, 2019)

Power of Hiroshima’s revival is shared with people in conflict areas

Shamsul Hadi Shams, 34, a resident of Higashihiroshima who works for the Hiroshima Office of the United Nations Institute for Training and Research (UNITAR), is making his presence felt in Hiroshima, more and more. Mr. Shams has spent over ten years in Hiroshima since leaving Afghanistan, his homeland, which still suffers from war and terrorist attacks.

Last December, 24 young people from Iraq came to the UNITAR Hiroshima Office, in Naka Ward, for a training program. The trainees, who were in their 20s and 30s, work for government institutions and universities in their nation. The training, marking its third year, is designed to develop local human resources who are able to contribute to advancing reconstruction in Iraq. Mr. Shams has been involved in this training program from the start. “Because the trainees are also from an area facing conflict, they feel that Hiroshima and its past is very important to them,” he explained. “They want to know a lot about Hiroshima. There is so much interest. When you suffer from war, you lose people, you lose family members. It’s so difficult to overcome these feelings of loss.” He added that despite the frustration and anger that people from countries like Afghanistan, Iraq, and South Sudan feel, they want to learn about Hiroshima, particularly the human side of how the people of Hiroshima have dealt with and overcome their own feelings of loss, anger, and sorrow.

Mr. Shams is also responsible for bringing in trainees from South Sudan, which is still plagued by civil war. He guides them around the Peace Memorial Park and the Peace Memorial Museum, and provides them with opportunities to interact with A-bomb survivors and second-generation survivors.

His career grew out of his own family’s hardships. As the eighth child of 11 children, he was born in Kabul, the capital of Afghanistan, five years after his nation was invaded by the former Soviet Union. His father, who worked for the government and for a university, was kept under surveillance by the communist regime. His family then fled to a location near Peshawar, in northwest Pakistan, which borders Afghanistan.

Mr. Shams’s eldest brother, who had been studying at a university in Saudi Arabia, joined Afghan civilians, backed by the United States, to fight again the communist government. He lost his life in a bombing by the Soviet military in eastern Afghanistan. His body, which was burned severely and was missing a leg, was brought back to his family in Pakistan. Reflecting on that event, Mr. Shams said, “It was my eldest brother. He was educated, and very smart, so my parents were counting on him. He was the backbone of our family so losing him was a big loss. I had never seen my father cry before, but when my brother died, he was in tears. That meant it was a huge loss for the whole family.”

Growing up as a refugee, Mr. Shams went to college and graduate school in Pakistan. But his homeland devolved into fierce fighting again. This was the war in Afghanistan, led by the United States after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The war made it impossible for him to return to Afghanistan and live there, where a state of chaos ensued as a result of U.S. air strikes and terrorist attacks.

He came to Japan in 2007. With a scholarship from the Japanese Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, he entered the doctoral program in the Graduate School for International Development and Cooperation at Hiroshima University. Explaining why he chose to study in Hiroshima, Mr. Shams said that he had wondered what Hiroshima now looked like when he learned about the atomic bombing and the devastation of this nuclear attack when he was in high school in Pakistan. He added, “I was really inspired by the story of Hiroshima and I wanted to come here to study, to learn about what happened during the war, how it happened, and how the people of Hiroshima overcame this tragedy and their hardships.”

A week after arriving in Hiroshima, he saw the A-bomb Dome up close and was very moved by the experience. “My experience of that place was my inspiration,” he said. “I was so moved. For me, the A-bomb Dome is a time machine. When you look at it, it takes you right back to August 6, 1945. I can visualize the scenes of that time in my mind. Maybe it’s the combination of Afghanistan and Hiroshima. There’s a very close connection between the two.”

During his studies at the graduate school, he learned about reconstruction and conflict resolution, then received his Ph.D. He was hired by UNITAR in 2012.

The long war in Afghanistan still goes on, with U.S. forces stationed there under the current U.S. administration of President Donald Trump and Islamic extremists again gaining influence in the region. Peace talks between the Afghan government and the Taliban, the armed opposition group, have made only partial progress. In Jalalabad, the city in eastern Afghanistan where his parents’ home still stands, suicide bomb attacks are taking place with alarming frequency. Mr. Shams has been unable to return there as often as before.

“I always wanted to do work that could lend support to people affected by conflict, poverty, and a lack of security, such as my own nation Afghanistan as well as countries like Iraq and South Sudan. UNITAR Hiroshima is the best platform for me to do this work. In this way, I can create bridges between Hiroshima and all the countries I work with.” He went on, “I wanted to help spread Hiroshima’s message, which is the message of peace, resilience, and self-reliance. I feel eager and happy to share this message with others.”

Mr. Shams’s passion for this work, which led him to join UNITAR, can now be seen in his personal activities, too. He has translated a picture book about Sadako Sasaki into his native language for distribution back in Afghanistan. And with his Japanese wife and friends, whom he met during his time in Hiroshima, he plans to publish a picture book about Hiroshima’s A-bombed trees, which survived the tragic bombing, in Afghanistan this spring.

(Originally published on January 28, 2019)