Survivors’ Stories: Kaneji Ota, 79, Naka Ward, Hiroshima: Fled to river to escape raging flames

Jan. 14, 2019

by Yumi Kanazaki, Staff Writer

Family takes shelter under wet bedding

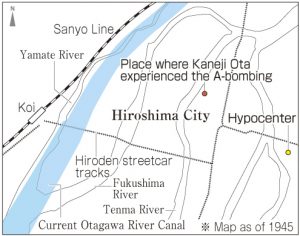

“I want to say it loudly, over and over, that there must be no more inhumane nuclear attacks,” said Kaneji Ota, 79. The resident of Naka Ward was only 900 meters from the hypocenter when the atomic bomb exploded above the city of Hiroshima. The experience he and his family endured, in fleeing from the raging flames, was seared into his mind.

Mr. Ota was five years old and living with his father Kinichi, his mother Yoshiko, and his three-year-old brother Shozo at their home in present-day Hirose-machi in Naka Ward. On August 6, 1945, he was set to leave his house to go to his kindergarten. As he followed his mother to the front door, they were exposed to the bomb’s blinding flash and he blacked out.

He heard his mother call out for him then found himself trapped beneath the collapsed house. His father had not yet left for work so the four members of the family crept out from under the debris and fled to the nearby Tenma River. They had to escape through a sea of fire.

On the stone steps at the riverbank, used as a landing spot, were scores of charred bodies. Someone grabbed onto his ankle and begged for water. “The person had a weak grip, and I can’t forget the feel of the skin peeling off when I pulled my leg away,” Mr. Ota said.

His father took some wood that was floating down the river and put it on the bank of the river. He then got some bedding that from the water and placed it on top of the wood. The family bathed in the river, clogged with the wreckage of houses and the bodies of people and horses. Then they hid beneath the bedding to avoid the blistering heat.

They waited for low tide, when the water level dropped, then crossed the Tenma, Fukushima, and Yamate rivers. The children held their parents’ hands as they sought to avoid stepping on corpses in the sand. On a hill behind today’s Koi train station, the family had a small house where they could stay in an emergency.

Because his mother protected him from the bomb’s heat rays, her upper body was badly burned, up to her neck. Mr. Ota still suffered from wounds, though, and they became infested with maggots. As a result of her exposure to the radiation that was released by the bomb, his mother lost all her hair, an acute aftereffect. Mr. Ota saw her weeping in front of a mirror. “Then all of us found that we were suffering from the same condition,” he said. “We ate up all the sweet potatoes we had, but we were still too hungry and weak to get up off the floor.” His mother was badly injured, so he and his father had to go in search of food, but they struggled to rise above their hardships. Around November, his mother sought refuge with relatives in Mihara, while his father and the children went to Takehara.

The following year, the family returned to where their house had stood. Mr. Ota and his father collected scraps of wood that were charred in the atomic bombing and built a “black house.” He entered what is now Honkawa Elementary School, the school closest to the hypocenter. He recalled, “We were so short of food that we had to pick the leaves off weeds, which we called ‘railroad weeds,’ and put them in dumplings for our lunches for school.”

Despite adverse circumstances, Mr. Ota continued his studies then landed a job at the Japan National Railways. After the company was privatized and became Japan Railways, he was temporarily transferred to an organization involved in the launch of the Astram Line, the city’s new passenger transit system. He also delivered instructions on how to operate the Shinkansen bullet train system and made string diagrams. He said he was afraid that the atomic bombing would be forgotten. “But I was busy and didn’t want to remember those terrible scenes,” he said. “I didn’t talk about what happened with the members of my family or my children.”

But he had a change of heart about five years ago, while taking part in an annual memorial service for the victims of the atomic bombing that he had attended for decades as the head of a local social welfare council.

In the Hirose area, many people are believed to have been killed instantly. It was almost miraculous how the Ota family and a few others were able to return to live where they had resided before the bombing. He began to think that he should go beyond his fears and, as a survivor, take action and tell about his experience to younger generations.

In 2015, he started sharing his experience with students on school trips. Since it’s not easy for older survivors to continue speaking about their experiences, Mr. Ota believes that the “relatively young survivors” like him should become more active. He said that nuclear weapons are incredibly brutal weapons with the radiation they release causing survivors to suffer from perpetual illnesses. Hoping that younger generations will carry on his wish for peace and the elimination of nuclear arms, he asks students to share what they have learned in Hiroshima to their parents, siblings, and friends.

Teenagers’ impressions

Am I doing enough?

Mr. Ota said that he started talking about his experience because he wanted to take action rather than just feeling afraid that the atomic bombing would be forgotten. I have a lot of opportunity to listen to survivors’ stories and write articles. But I ask myself if I’m satisfied that I’m doing all I can. I should think more about what I can do to convey to younger people what happened in the atomic bombing. (Hitoha Katsura, 14)

We should push ourselves harder than ever

Mr. Ota said that he didn’t want to remember what he saw after the atomic bombing. He saw the city destroyed and the bodies of many victims. It must have been more than a five-year-old boy could endure. This spring I will leave Hiroshima to go to college. I may find that a lot of people don’t know much about the atomic bombing. But I think we should push ourselves harder than ever to take up the wish of Mr. Ota and other survivors. (Honoka Ikeda, 18)

(Originally published on January 14, 2019)

Family takes shelter under wet bedding

“I want to say it loudly, over and over, that there must be no more inhumane nuclear attacks,” said Kaneji Ota, 79. The resident of Naka Ward was only 900 meters from the hypocenter when the atomic bomb exploded above the city of Hiroshima. The experience he and his family endured, in fleeing from the raging flames, was seared into his mind.

Mr. Ota was five years old and living with his father Kinichi, his mother Yoshiko, and his three-year-old brother Shozo at their home in present-day Hirose-machi in Naka Ward. On August 6, 1945, he was set to leave his house to go to his kindergarten. As he followed his mother to the front door, they were exposed to the bomb’s blinding flash and he blacked out.

He heard his mother call out for him then found himself trapped beneath the collapsed house. His father had not yet left for work so the four members of the family crept out from under the debris and fled to the nearby Tenma River. They had to escape through a sea of fire.

On the stone steps at the riverbank, used as a landing spot, were scores of charred bodies. Someone grabbed onto his ankle and begged for water. “The person had a weak grip, and I can’t forget the feel of the skin peeling off when I pulled my leg away,” Mr. Ota said.

His father took some wood that was floating down the river and put it on the bank of the river. He then got some bedding that from the water and placed it on top of the wood. The family bathed in the river, clogged with the wreckage of houses and the bodies of people and horses. Then they hid beneath the bedding to avoid the blistering heat.

They waited for low tide, when the water level dropped, then crossed the Tenma, Fukushima, and Yamate rivers. The children held their parents’ hands as they sought to avoid stepping on corpses in the sand. On a hill behind today’s Koi train station, the family had a small house where they could stay in an emergency.

Because his mother protected him from the bomb’s heat rays, her upper body was badly burned, up to her neck. Mr. Ota still suffered from wounds, though, and they became infested with maggots. As a result of her exposure to the radiation that was released by the bomb, his mother lost all her hair, an acute aftereffect. Mr. Ota saw her weeping in front of a mirror. “Then all of us found that we were suffering from the same condition,” he said. “We ate up all the sweet potatoes we had, but we were still too hungry and weak to get up off the floor.” His mother was badly injured, so he and his father had to go in search of food, but they struggled to rise above their hardships. Around November, his mother sought refuge with relatives in Mihara, while his father and the children went to Takehara.

The following year, the family returned to where their house had stood. Mr. Ota and his father collected scraps of wood that were charred in the atomic bombing and built a “black house.” He entered what is now Honkawa Elementary School, the school closest to the hypocenter. He recalled, “We were so short of food that we had to pick the leaves off weeds, which we called ‘railroad weeds,’ and put them in dumplings for our lunches for school.”

Despite adverse circumstances, Mr. Ota continued his studies then landed a job at the Japan National Railways. After the company was privatized and became Japan Railways, he was temporarily transferred to an organization involved in the launch of the Astram Line, the city’s new passenger transit system. He also delivered instructions on how to operate the Shinkansen bullet train system and made string diagrams. He said he was afraid that the atomic bombing would be forgotten. “But I was busy and didn’t want to remember those terrible scenes,” he said. “I didn’t talk about what happened with the members of my family or my children.”

But he had a change of heart about five years ago, while taking part in an annual memorial service for the victims of the atomic bombing that he had attended for decades as the head of a local social welfare council.

In the Hirose area, many people are believed to have been killed instantly. It was almost miraculous how the Ota family and a few others were able to return to live where they had resided before the bombing. He began to think that he should go beyond his fears and, as a survivor, take action and tell about his experience to younger generations.

In 2015, he started sharing his experience with students on school trips. Since it’s not easy for older survivors to continue speaking about their experiences, Mr. Ota believes that the “relatively young survivors” like him should become more active. He said that nuclear weapons are incredibly brutal weapons with the radiation they release causing survivors to suffer from perpetual illnesses. Hoping that younger generations will carry on his wish for peace and the elimination of nuclear arms, he asks students to share what they have learned in Hiroshima to their parents, siblings, and friends.

Teenagers’ impressions

Am I doing enough?

Mr. Ota said that he started talking about his experience because he wanted to take action rather than just feeling afraid that the atomic bombing would be forgotten. I have a lot of opportunity to listen to survivors’ stories and write articles. But I ask myself if I’m satisfied that I’m doing all I can. I should think more about what I can do to convey to younger people what happened in the atomic bombing. (Hitoha Katsura, 14)

We should push ourselves harder than ever

Mr. Ota said that he didn’t want to remember what he saw after the atomic bombing. He saw the city destroyed and the bodies of many victims. It must have been more than a five-year-old boy could endure. This spring I will leave Hiroshima to go to college. I may find that a lot of people don’t know much about the atomic bombing. But I think we should push ourselves harder than ever to take up the wish of Mr. Ota and other survivors. (Honoka Ikeda, 18)

(Originally published on January 14, 2019)