Survivors’ Stories: Yasuko Yamaguchi, 86, Higashi Ward, Hiroshima: A-bombing claimed her parents, her grandmother, and two elder sisters

Mar. 11, 2019

Endured hardships to enter university at the age of 22

by Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer

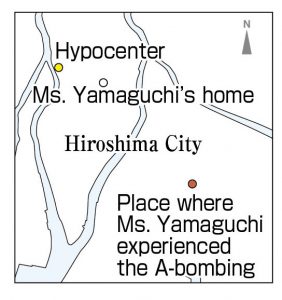

Yasuko Yamaguchi (née Kato), 86, was a first-year student at Hijiyama Girls’ High School (now Hijiyama Girls’ Junior and Senior High School in Minami Ward), which was located about 2.9 kilometers from the hypocenter. On the morning of August 6, she and her schoolmates gathered at the school before heading to their work site, where they were helping to tear down homes to create a fire lane in the event of air raids. But when she was in her classroom, she was suddenly enveloped by a blinding flash.

That morning, many students from junior high schools and girls’ high schools in Hiroshima were mobilized for this demolition work in the city center, and they suffered the atomic bombing at a close distance from the hypocenter. Ms. Yamaguchi and other students from Hijiyama Girls’ High School were able to survive the attack because the school principal had decided to have them assemble at the school, not at their work site. Still, the school building was hit hard by the bomb blast.

With her air-raid hood on her head, Ms. Yamaguchi ducked under her desk and covered her eyes, ears, and nose with her hands, but received injuries to both elbows, a knee, and her foot from fragments of flying glass. Her classmates were injured as well, and they were crying and moaning.

When she went out into the schoolyard, she saw a huge mushroom cloud in the sky. She fled to a small mountain and looked on as the city burned below, but she still felt that her family would be all right.

Her family had a clock shop in Horikawa-cho (now part of Naka Ward), located about 800 meters from the hypocenter. Ms. Yamaguchi was the sixth of seven children. Her parents, grandmother, her eldest sister Hatsuko, and her second-eldest sister Sueko, would surely be at home, she thought.

But the flames prevented her from approaching her neighborhood so that night she slept in the school dormitory. The next day, August 7, she went out searching for her family and happened to come across Hatsuko that evening. When Ms. Yamaguchi asked her sister about the rest of the family, Hatsuko replied, “They didn’t make it.”

Her home, a three-story building made of wood, collapsed instantly when it was hit by the bomb blast. According to Hatsuko, she was able to crawl out of the wreckage, but Sueko was trapped under a beam. From beneath the rubble, she heard her mother shout, “A bomb has hit our home! Help me, please!” Hatsuko tried to lift the beam pinning down Sueko, but was unable to move it. Hatsuko told Ms. Yamaguchi that she was forced to flee, and leave them behind, when fire began closing in.

The bodies of her parents and her grandmother, which were hardly recognizable, were found in the ruins of her home. Sueko, though, could not be located. Though her name was included on the list of victims that were taken to the East Drill Ground (now part of Higashi Ward), they were unable to find her. A dish with a flower pattern was found at the site where her home had stood. Ms. Yamaguchi still keeps it as a memento of her family.

Hatsuko and Ms. Yamaguchi, the two surviving sisters, evacuated to the home of a distant relative. Soon after that, Hatsuko came down with a fever and her hair fell out; her body then became covered with purple spots. She also bled from her nose and her eyes. Grieving with guilt over not being able to save the other members of her family, Hatsuko died 18 days after the atomic bombing.

After the war, Ms. Yamaguchi endured many hardships. With support from her relative, she went back to school and she was also aided financially by her elder brother, who returned to Japan from his military service in China. After she graduated from high school, she worked for a company in Osaka and saved money. Then, at the age of 22, she was able to enter Hiroshima University.

While working to help educate children with visual disabilities, she got married when she was 28, and had four children. Back in high school, she had gotten baptized to become Catholic as a result of the influence of an English teacher who lived in the dormitory with her. In this connection, she also contributed to a publication that collected the accounts of A-bomb survivors, including her efforts to interview Hugo Lassalle, a German priest who also experienced the Hiroshima bombing.

This year, Pope Francis is expected to visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the two A-bombed cities. Ms. Yamaguchi welcomes his visit, saying, “My wish is for people to unite in their minds and hearts, regardless of their religious or ethnic differences, and I hope this wish will be understood by as many people as possible through the Pope’s visit.”

Ms. Yamaguchi, with the dish that became a memento of her family, stressed that war must never be waged again because it inevitably turns children and those who are weaker into victims.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Impressed by her proactive efforts to realize her dream

Ms. Yamaguchi lost her parents because of the bombing, but her strong will and determination to continue her education enabled her to attend university. I was impressed by her proactive nature and her resolve, which led to realizing her dream of working in education in Hiroshima. Because those of my generation have grown up at a time of abundance, we have to make sincere efforts to study hard and gain a lot of experience in order to create a world where no one will suffer from war again. (Naruho Matsuzaki, 18)

The bombing was such a terrible and cruel thing

Ms. Yamaguchi’s eldest sister made desperate efforts to save other family members who were trapped under the wreckage of their home, but she had no choice but to flee when the fire approached. When I imagined the feelings of her sister, who was unable to save these other family members, and Ms. Yamaguchi, who heard the account from her, I felt that the atomic bombing, which stole away their loved ones, was such a terrible and cruel thing. I’m going to tell many other people about the tragedy of the atomic bombing so that the same kind of tragedy will never take place again. (Honoka Ikeda, 18)

(Originally published on March 11, 2019)

by Sakiko Masuda, Staff Writer

Yasuko Yamaguchi (née Kato), 86, was a first-year student at Hijiyama Girls’ High School (now Hijiyama Girls’ Junior and Senior High School in Minami Ward), which was located about 2.9 kilometers from the hypocenter. On the morning of August 6, she and her schoolmates gathered at the school before heading to their work site, where they were helping to tear down homes to create a fire lane in the event of air raids. But when she was in her classroom, she was suddenly enveloped by a blinding flash.

That morning, many students from junior high schools and girls’ high schools in Hiroshima were mobilized for this demolition work in the city center, and they suffered the atomic bombing at a close distance from the hypocenter. Ms. Yamaguchi and other students from Hijiyama Girls’ High School were able to survive the attack because the school principal had decided to have them assemble at the school, not at their work site. Still, the school building was hit hard by the bomb blast.

With her air-raid hood on her head, Ms. Yamaguchi ducked under her desk and covered her eyes, ears, and nose with her hands, but received injuries to both elbows, a knee, and her foot from fragments of flying glass. Her classmates were injured as well, and they were crying and moaning.

When she went out into the schoolyard, she saw a huge mushroom cloud in the sky. She fled to a small mountain and looked on as the city burned below, but she still felt that her family would be all right.

Her family had a clock shop in Horikawa-cho (now part of Naka Ward), located about 800 meters from the hypocenter. Ms. Yamaguchi was the sixth of seven children. Her parents, grandmother, her eldest sister Hatsuko, and her second-eldest sister Sueko, would surely be at home, she thought.

But the flames prevented her from approaching her neighborhood so that night she slept in the school dormitory. The next day, August 7, she went out searching for her family and happened to come across Hatsuko that evening. When Ms. Yamaguchi asked her sister about the rest of the family, Hatsuko replied, “They didn’t make it.”

Her home, a three-story building made of wood, collapsed instantly when it was hit by the bomb blast. According to Hatsuko, she was able to crawl out of the wreckage, but Sueko was trapped under a beam. From beneath the rubble, she heard her mother shout, “A bomb has hit our home! Help me, please!” Hatsuko tried to lift the beam pinning down Sueko, but was unable to move it. Hatsuko told Ms. Yamaguchi that she was forced to flee, and leave them behind, when fire began closing in.

The bodies of her parents and her grandmother, which were hardly recognizable, were found in the ruins of her home. Sueko, though, could not be located. Though her name was included on the list of victims that were taken to the East Drill Ground (now part of Higashi Ward), they were unable to find her. A dish with a flower pattern was found at the site where her home had stood. Ms. Yamaguchi still keeps it as a memento of her family.

Hatsuko and Ms. Yamaguchi, the two surviving sisters, evacuated to the home of a distant relative. Soon after that, Hatsuko came down with a fever and her hair fell out; her body then became covered with purple spots. She also bled from her nose and her eyes. Grieving with guilt over not being able to save the other members of her family, Hatsuko died 18 days after the atomic bombing.

After the war, Ms. Yamaguchi endured many hardships. With support from her relative, she went back to school and she was also aided financially by her elder brother, who returned to Japan from his military service in China. After she graduated from high school, she worked for a company in Osaka and saved money. Then, at the age of 22, she was able to enter Hiroshima University.

While working to help educate children with visual disabilities, she got married when she was 28, and had four children. Back in high school, she had gotten baptized to become Catholic as a result of the influence of an English teacher who lived in the dormitory with her. In this connection, she also contributed to a publication that collected the accounts of A-bomb survivors, including her efforts to interview Hugo Lassalle, a German priest who also experienced the Hiroshima bombing.

This year, Pope Francis is expected to visit Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the two A-bombed cities. Ms. Yamaguchi welcomes his visit, saying, “My wish is for people to unite in their minds and hearts, regardless of their religious or ethnic differences, and I hope this wish will be understood by as many people as possible through the Pope’s visit.”

Ms. Yamaguchi, with the dish that became a memento of her family, stressed that war must never be waged again because it inevitably turns children and those who are weaker into victims.

Teenagers’ Impressions

Impressed by her proactive efforts to realize her dream

Ms. Yamaguchi lost her parents because of the bombing, but her strong will and determination to continue her education enabled her to attend university. I was impressed by her proactive nature and her resolve, which led to realizing her dream of working in education in Hiroshima. Because those of my generation have grown up at a time of abundance, we have to make sincere efforts to study hard and gain a lot of experience in order to create a world where no one will suffer from war again. (Naruho Matsuzaki, 18)

The bombing was such a terrible and cruel thing

Ms. Yamaguchi’s eldest sister made desperate efforts to save other family members who were trapped under the wreckage of their home, but she had no choice but to flee when the fire approached. When I imagined the feelings of her sister, who was unable to save these other family members, and Ms. Yamaguchi, who heard the account from her, I felt that the atomic bombing, which stole away their loved ones, was such a terrible and cruel thing. I’m going to tell many other people about the tragedy of the atomic bombing so that the same kind of tragedy will never take place again. (Honoka Ikeda, 18)

(Originally published on March 11, 2019)