Survivors’ Stories: Norio Morimoto, 90, Hiroshima: “My friend blocked the bomb’s heat rays”

Apr. 1, 2019

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

For about 40 years, Norio Morimoto, 90, of Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, has shared his A-bomb account to students visiting Hiroshima on school trips. However, for as long as 17 months he has been forced to stop giving these talks because he had to have both of his legs amputated at the knee due to a bacterial infection. But his fervent desire to “tell as many students as possible about the tragedy of the war” is driving him to engage in strenuous rehabilitation and he will be able to resume his speaking activities next month.

Mr. Morimoto’s parents ran a wholesale business handling shoes in Fukushima-cho (now part of Nishi Ward). He entered Hiroshima Municipal Commercial School (now Hiroshima Municipal Hiroshima Commercial High School), and dreamed of becoming a teacher. However, nearly all of his classes were canceled because of the war. After having been forced to work at a munitions factory for the war effort, he graduated from the school in the spring of 1945, one year earlier than scheduled. Then he started working as a substitute teacher at Furuta National School (now Furuta Elementary School). He was 16 years old at the time.

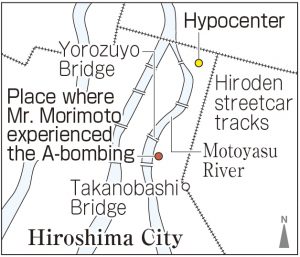

On the morning of August 6, Mr. Morimoto took a day off and headed to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital in Sendamachi (now part of Naka Ward) by streetcar to be treated for a chronic disease. As he got off at Takanobashi station, he came across Morio Ozu, a former classmate who had moved to Tokyo. Mr. Ozu said that he was bombed out of his home during the air raid in Tokyo and returned to Hiroshima. They walked toward Otemachi (now part of Naka Ward), where Mr. Ozu’s home was, as Mr. Morimoto listened to Mr. Ozu talk about his experiences.

As they came near Yorozuyo Bridge, there was an abrupt yellowish flash in front of them, brighter than the sun, then came a tremendous blast. Mr. Morimoto was blown off his feet and he blacked out. When he came to, everything was pitch-dark. He was 1.1 kilometers from the hypocenter.

Mr. Morimoto groped for his friend, and found someone who resembled him, but the person was scorched black and already dead. Fearing that there might be a second bomb, he quickly fled that site. However, he became caught up in a whirlpool of people who were running about in confusion, and, before he knew it, he had blundered into a sea of flames.

His clothes were in tatters, and his face and arms were burned, the skin peeling away and dangling down. And he was unable to open his eyes because his eyelids had been burned in a closed state. Still, he was determined “not to give up” and, steeling himself, he sought to flee. As he was running about, he was loaded onto a military truck pursuing rescue efforts. Mr. Morimoto was taken to a field hospital which used to be the Army’s Marine Training Division, located at the site of today’s Ujina West Plant of Mazda Motor Corporation. The hospital was packed with casualties who were groaning, “It’s hot” or “It hurts” and dying one after another. The young woman who was next to him, and helped care for him, also died.

At the end of August, Mr. Morimoto’s uncle came to pick him up from the village of Kamokimi (now the city of Kashihara) in Nara Prefecture, where his parents were from. Pus was oozing from Mr. Morimoto’s face and head, which were infested with maggots. On the way to the village, his concerned uncle covered Mr. Morimoto’s head with a kerchief and would not permit him to look in a mirror.

The remains of Mr. Ozu, who was with Mr. Morimoto until the moment the A-bomb exploded, went missing. “If only I had dragged his burnt body out. I was a demon then, not a human,” said Mr. Morimoto, still haunted by remorse. He believes his friend saved his life by blocking the bomb’s heat rays. Every August 6, he would be part of a choir that sang “Requiem,” composed by Mozart or Fauré, to personally mourn the death of his friend, who lost his life while still so young.

During his break due to illness, Mr. Morimoto has felt rising concern about the escalating military buildup taking place in the world. He said, “Something tragic could happen if this trend continues. I truly hope Japan does not become a country that drags its people into a war.” He is determined to continue making appeals with all his might, even in his hoarse voice, so that his words will move children’s minds and hearts.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I won’t turn away from the world’s conflicts

Mr. Morimoto said that his uncle warned him not to look in a mirror because of his severe burns. Just imagining myself in Mr. Morimoto’s place is scary. He stressed many times that war should be avoided at all costs. His way of living taught me the importance of conveying our messages to others. I will actively try to learn about the past and the conflicts around the world without turning away my eyes. (Yuri Furohashi, first-year high school student)

Remorse felt by Mr. Morimoto must never be repeated

Mr. Morimoto said, “I tried to cover my eyes and ear, and hit the ground, but I was blown off my feet by the blast.” His words made me realize how destructive the atomic bomb was. He feels deep remorse over leaving his friend behind, telling us, “I abandoned him, and for that I feel much more than regret.” I plan to tell people about the horrors of the atomic bomb and the war so we will never wage another war and lose people that are close to us. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi, third-year high school student)

(Originally published on April 1, 2019)

For about 40 years, Norio Morimoto, 90, of Nishi Ward, Hiroshima, has shared his A-bomb account to students visiting Hiroshima on school trips. However, for as long as 17 months he has been forced to stop giving these talks because he had to have both of his legs amputated at the knee due to a bacterial infection. But his fervent desire to “tell as many students as possible about the tragedy of the war” is driving him to engage in strenuous rehabilitation and he will be able to resume his speaking activities next month.

Mr. Morimoto’s parents ran a wholesale business handling shoes in Fukushima-cho (now part of Nishi Ward). He entered Hiroshima Municipal Commercial School (now Hiroshima Municipal Hiroshima Commercial High School), and dreamed of becoming a teacher. However, nearly all of his classes were canceled because of the war. After having been forced to work at a munitions factory for the war effort, he graduated from the school in the spring of 1945, one year earlier than scheduled. Then he started working as a substitute teacher at Furuta National School (now Furuta Elementary School). He was 16 years old at the time.

On the morning of August 6, Mr. Morimoto took a day off and headed to the Hiroshima Red Cross Hospital in Sendamachi (now part of Naka Ward) by streetcar to be treated for a chronic disease. As he got off at Takanobashi station, he came across Morio Ozu, a former classmate who had moved to Tokyo. Mr. Ozu said that he was bombed out of his home during the air raid in Tokyo and returned to Hiroshima. They walked toward Otemachi (now part of Naka Ward), where Mr. Ozu’s home was, as Mr. Morimoto listened to Mr. Ozu talk about his experiences.

As they came near Yorozuyo Bridge, there was an abrupt yellowish flash in front of them, brighter than the sun, then came a tremendous blast. Mr. Morimoto was blown off his feet and he blacked out. When he came to, everything was pitch-dark. He was 1.1 kilometers from the hypocenter.

Mr. Morimoto groped for his friend, and found someone who resembled him, but the person was scorched black and already dead. Fearing that there might be a second bomb, he quickly fled that site. However, he became caught up in a whirlpool of people who were running about in confusion, and, before he knew it, he had blundered into a sea of flames.

His clothes were in tatters, and his face and arms were burned, the skin peeling away and dangling down. And he was unable to open his eyes because his eyelids had been burned in a closed state. Still, he was determined “not to give up” and, steeling himself, he sought to flee. As he was running about, he was loaded onto a military truck pursuing rescue efforts. Mr. Morimoto was taken to a field hospital which used to be the Army’s Marine Training Division, located at the site of today’s Ujina West Plant of Mazda Motor Corporation. The hospital was packed with casualties who were groaning, “It’s hot” or “It hurts” and dying one after another. The young woman who was next to him, and helped care for him, also died.

At the end of August, Mr. Morimoto’s uncle came to pick him up from the village of Kamokimi (now the city of Kashihara) in Nara Prefecture, where his parents were from. Pus was oozing from Mr. Morimoto’s face and head, which were infested with maggots. On the way to the village, his concerned uncle covered Mr. Morimoto’s head with a kerchief and would not permit him to look in a mirror.

The remains of Mr. Ozu, who was with Mr. Morimoto until the moment the A-bomb exploded, went missing. “If only I had dragged his burnt body out. I was a demon then, not a human,” said Mr. Morimoto, still haunted by remorse. He believes his friend saved his life by blocking the bomb’s heat rays. Every August 6, he would be part of a choir that sang “Requiem,” composed by Mozart or Fauré, to personally mourn the death of his friend, who lost his life while still so young.

During his break due to illness, Mr. Morimoto has felt rising concern about the escalating military buildup taking place in the world. He said, “Something tragic could happen if this trend continues. I truly hope Japan does not become a country that drags its people into a war.” He is determined to continue making appeals with all his might, even in his hoarse voice, so that his words will move children’s minds and hearts.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I won’t turn away from the world’s conflicts

Mr. Morimoto said that his uncle warned him not to look in a mirror because of his severe burns. Just imagining myself in Mr. Morimoto’s place is scary. He stressed many times that war should be avoided at all costs. His way of living taught me the importance of conveying our messages to others. I will actively try to learn about the past and the conflicts around the world without turning away my eyes. (Yuri Furohashi, first-year high school student)

Remorse felt by Mr. Morimoto must never be repeated

Mr. Morimoto said, “I tried to cover my eyes and ear, and hit the ground, but I was blown off my feet by the blast.” His words made me realize how destructive the atomic bomb was. He feels deep remorse over leaving his friend behind, telling us, “I abandoned him, and for that I feel much more than regret.” I plan to tell people about the horrors of the atomic bomb and the war so we will never wage another war and lose people that are close to us. (Tokitsuna Kawagishi, third-year high school student)

(Originally published on April 1, 2019)