Elementary schools in Hiroshima open peace museums to learn about the atomic bombing as local experiences

Jun. 24, 2019

by Miho Kuwajima and Kyoko Niiyama, Staff Writers

Elementary schools located in the heart of Hiroshima, which were devastated in the atomic bombing, are making efforts to establish “peace museums” by using empty classrooms and other places. The written accounts and A-bomb drawings made by survivors with strong ties to the area, as well as photos of the neighborhood taken before and after the war, are being displayed. These rooms at the schools have become a place for children to learn about the damage wrought by the atomic bombing and to think about peace in their everyday lives. These small “A-bomb museums” are also useful for those who visit Hiroshima for peace studies.

Students learn from accounts and drawings

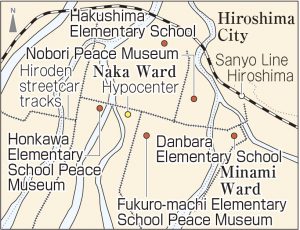

Hakushima Elementary School in Naka Ward has a local history and culture museum in its annex, displaying artifacts that include Yayoi wares, farming tools that had been used for many years, and a red public telephone with a dial. Sayuri Morisada, 55, the principal of Hakushima Elementary School, explained, “Next January we will relocate the museum to the second floor of the south school building. We plan to review and reorganize the contents of the exhibition and, as a pillar of the display, focus on information about the damage done to the school and the neighborhood caused by the atomic bombing.”

Hakushima Elementary School, which was Hakushima National School at the time of the bombing, currently stands close to where the A-bombed school was located, about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. The lives of the principal and around 100 students were quickly snuffed out by the atomic bomb. Hakushima Elementary School is now planning to share accounts and drawings made by teachers and students who survived the bombing and a map of A-bomb artifacts in the Hakushima district. A project team, composed of a teacher who was born before the war and local residents, will soon be formed to involve the community and carry out this plan.

In devising their plan for this renovation, they looked to the Nobori Peace Museum at Nobori-cho Elementary School, in Naka Ward, as an example. Sadako Sasaki was a young Japanese girl who survived the atomic bombing and attended Nobori-cho Elementary School, but was struck down by radiation-induced leukemia 10 years later. After her death, Sadako became the inspiration for the Children’s Peace Monument in the Peace Memorial Park. Nobori-cho Elementary School opened its museum in May 2018 on the first floor of the school building, displaying two paper cranes folded by Sadako, about 100 pictures of and around the school taken before the war, and other items.

Last fall, Nobori-cho Elementary School initiated the “Nobori Peace Walk,” in which older students guide younger students on a walk around the school grounds to visit remnants of the atomic bombing. This past April they formed a “Peace Committee” with 15 students from the fifth and sixth grades instructing children in lower grades how to make a paper crane. The students first learn about the catastrophe created by the atomic bombing by visiting the school museum then engage in these peace activities. The museum has become a new base where students are showing their own initiative to learn about peace.

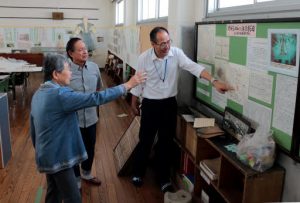

Danji Nishioka, 11 years old and in sixth grade, said, “Every time I come to the museum, I think about what peace is.” Teruhiko Fujikawa, 56, the principal of Nobori-cho Elementary School, shared his hopes by saying, “I’d like the students to become people who think about peace and talk about it in their own words.”

The school opens the museum to the public every Friday, but by appointment only. Although this adds to the work load of the school staff, they are pleased to welcome students visiting Hiroshima on school trips or international visitors who are interested in Sadako’s story.

Yasushi Shimamoto, 58, a former principal of Nobori-cho Elementary School who was appointed to head up Danbara Elementary School in Minami Ward this spring, is working to set up a museum at his new workplace. “The Danbara district also has many artifacts and accounts. We should create a school museum while we are still able to gain the cooperation of A-bomb survivors who can share their accounts or the elderly who experienced the war,” Mr. Shimamoto said firmly. Yoshinori Kato, 91 and a resident of Nishi Ward, continues to speak about his A-bomb experience in the district. He plans to donate his account and his A-bomb drawings to the school.

The Hiroshima City Board of Education is also making positive efforts to promote this movement. Naomi Arase, the board’s vice-director, said, “We will introduce their activities to other schools as examples of places to pursue peace studies, where children can easily understand and feel the A-bomb tragedy as a problem close to them by making the best of the local characteristics, and the local community can contribute their strengths.”

Making use of A-bombed buildings at elementary schools

Two elementary schools near the hypocenter in Hiroshima are making use of A-bombed school buildings as museums, which are open to the public. While these museums have become bases for students to learn about peace, they have also been incorporated in the “peace tourism” routes promoted by the City of Hiroshima.

Honkawa Elementary School in Naka Ward, which is located about 410 meters from the hypocenter, opened its peace museum in 1988. Over the last school year, they received more than 33,000 visitors. Starting this spring, the museum is open every day, including weekends and holidays. The school principal, Yuka Okada, 53, said, “Visitors from around the world give our students the opportunity to rediscover the importance of Honkawa Elementary School as an A-bombed school.”

Fukuro-machi Elementary School opened its peace museum 17 years ago. On the surface of the museum wall are messages once left by survivors asking about the safety of others in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, conveying the chaos at the school that was transformed into a first-aid station. Occasionally, sixth graders lead a tour for international visitors, in English, and make a handwritten newspaper which explains what they have learned from the museum.

Meanwhile, peace museums are also found in two elementary schools in Nagasaki, another city devastated by an atomic bomb. Shiroyama Elementary School, located near the hypocenter, has opened part of the A-bombed building to the public as a “peace memorial museum.” Sixth graders sometimes serve as guides for students visiting the museum on school trips. Yamazato Elementary School lost about 1,300 students in the A-bomb attack. Their “atomic bomb museum” displays A-bombed roof tiles and pieces of glass that were melted by the bomb’s heat rays.

(Originally published on June 24, 2019)

Elementary schools located in the heart of Hiroshima, which were devastated in the atomic bombing, are making efforts to establish “peace museums” by using empty classrooms and other places. The written accounts and A-bomb drawings made by survivors with strong ties to the area, as well as photos of the neighborhood taken before and after the war, are being displayed. These rooms at the schools have become a place for children to learn about the damage wrought by the atomic bombing and to think about peace in their everyday lives. These small “A-bomb museums” are also useful for those who visit Hiroshima for peace studies.

Students learn from accounts and drawings

Hakushima Elementary School in Naka Ward has a local history and culture museum in its annex, displaying artifacts that include Yayoi wares, farming tools that had been used for many years, and a red public telephone with a dial. Sayuri Morisada, 55, the principal of Hakushima Elementary School, explained, “Next January we will relocate the museum to the second floor of the south school building. We plan to review and reorganize the contents of the exhibition and, as a pillar of the display, focus on information about the damage done to the school and the neighborhood caused by the atomic bombing.”

Hakushima Elementary School, which was Hakushima National School at the time of the bombing, currently stands close to where the A-bombed school was located, about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. The lives of the principal and around 100 students were quickly snuffed out by the atomic bomb. Hakushima Elementary School is now planning to share accounts and drawings made by teachers and students who survived the bombing and a map of A-bomb artifacts in the Hakushima district. A project team, composed of a teacher who was born before the war and local residents, will soon be formed to involve the community and carry out this plan.

In devising their plan for this renovation, they looked to the Nobori Peace Museum at Nobori-cho Elementary School, in Naka Ward, as an example. Sadako Sasaki was a young Japanese girl who survived the atomic bombing and attended Nobori-cho Elementary School, but was struck down by radiation-induced leukemia 10 years later. After her death, Sadako became the inspiration for the Children’s Peace Monument in the Peace Memorial Park. Nobori-cho Elementary School opened its museum in May 2018 on the first floor of the school building, displaying two paper cranes folded by Sadako, about 100 pictures of and around the school taken before the war, and other items.

Last fall, Nobori-cho Elementary School initiated the “Nobori Peace Walk,” in which older students guide younger students on a walk around the school grounds to visit remnants of the atomic bombing. This past April they formed a “Peace Committee” with 15 students from the fifth and sixth grades instructing children in lower grades how to make a paper crane. The students first learn about the catastrophe created by the atomic bombing by visiting the school museum then engage in these peace activities. The museum has become a new base where students are showing their own initiative to learn about peace.

Danji Nishioka, 11 years old and in sixth grade, said, “Every time I come to the museum, I think about what peace is.” Teruhiko Fujikawa, 56, the principal of Nobori-cho Elementary School, shared his hopes by saying, “I’d like the students to become people who think about peace and talk about it in their own words.”

The school opens the museum to the public every Friday, but by appointment only. Although this adds to the work load of the school staff, they are pleased to welcome students visiting Hiroshima on school trips or international visitors who are interested in Sadako’s story.

Yasushi Shimamoto, 58, a former principal of Nobori-cho Elementary School who was appointed to head up Danbara Elementary School in Minami Ward this spring, is working to set up a museum at his new workplace. “The Danbara district also has many artifacts and accounts. We should create a school museum while we are still able to gain the cooperation of A-bomb survivors who can share their accounts or the elderly who experienced the war,” Mr. Shimamoto said firmly. Yoshinori Kato, 91 and a resident of Nishi Ward, continues to speak about his A-bomb experience in the district. He plans to donate his account and his A-bomb drawings to the school.

The Hiroshima City Board of Education is also making positive efforts to promote this movement. Naomi Arase, the board’s vice-director, said, “We will introduce their activities to other schools as examples of places to pursue peace studies, where children can easily understand and feel the A-bomb tragedy as a problem close to them by making the best of the local characteristics, and the local community can contribute their strengths.”

Making use of A-bombed buildings at elementary schools

Two elementary schools near the hypocenter in Hiroshima are making use of A-bombed school buildings as museums, which are open to the public. While these museums have become bases for students to learn about peace, they have also been incorporated in the “peace tourism” routes promoted by the City of Hiroshima.

Honkawa Elementary School in Naka Ward, which is located about 410 meters from the hypocenter, opened its peace museum in 1988. Over the last school year, they received more than 33,000 visitors. Starting this spring, the museum is open every day, including weekends and holidays. The school principal, Yuka Okada, 53, said, “Visitors from around the world give our students the opportunity to rediscover the importance of Honkawa Elementary School as an A-bombed school.”

Fukuro-machi Elementary School opened its peace museum 17 years ago. On the surface of the museum wall are messages once left by survivors asking about the safety of others in the aftermath of the atomic bombing, conveying the chaos at the school that was transformed into a first-aid station. Occasionally, sixth graders lead a tour for international visitors, in English, and make a handwritten newspaper which explains what they have learned from the museum.

Meanwhile, peace museums are also found in two elementary schools in Nagasaki, another city devastated by an atomic bomb. Shiroyama Elementary School, located near the hypocenter, has opened part of the A-bombed building to the public as a “peace memorial museum.” Sixth graders sometimes serve as guides for students visiting the museum on school trips. Yamazato Elementary School lost about 1,300 students in the A-bomb attack. Their “atomic bomb museum” displays A-bombed roof tiles and pieces of glass that were melted by the bomb’s heat rays.

(Originally published on June 24, 2019)