Survivors’ Stories: Kiyoko Takenaga, 88, Hiroshima: “Fled to north in bare feet for my life”

Sep. 10, 2019

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Kiyoko Takenaga, 88, lost her mother and two sisters because of the atomic bomb. She still resides in the area where she was born and raised. She has a lot of memories of time spent with her family in the area. The area, Ebisu-cho (now Horikawa-cho in Naka Ward, Hiroshima), was a bustling shopping district lined with dress shops and movie theaters, prior to the war. Despite the destruction that occurred, her family remained there; Ms. Takenaga’s father tenaciously rebuilding their home on the site where their former house once stood.

In August of 1945, there were six in her family: her father Santaro (then 48), mother Shin (43), an older sister, two younger sisters and Ms. Takenaga herself. Santaro had previously run a signboard shop in front of the Ebisu Shrine, while also painting store signs and a theater marquee. Around 1940, he changed jobs and became an antique dealer. He was ahead of the times, wearing fashionable clothes, and quick to adopt new technology—for example, obtaining a radio and a phonograph before anyone else.

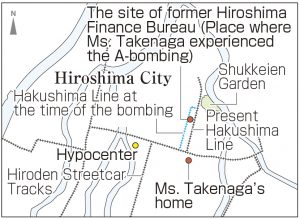

On August 6, 1945, Ms. Takenaga, then a third-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin High School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior & Senior High School), was working as a mobilized student at the Hiroshima Finance Bureau in Hatchobori (now part of Naka Ward). She sat down at her desk at 8:00 a.m. Not long after, she saw a very bright yellow flash of light and was knocked from her seat.

The Bureau was located about 800 meters from the hypocenter. The ceiling above her in the Bureau’s two-story wooden building collapsed, and the area went completely dark. Ms. Takenaga managed to escape injury by getting under the desk, but her classmate who sat in front of her seemed to have been pinned beneath something. “Mother, help me. Oh God! Help me.” Ms. Takenaga heard her tearful voice calling.

She then heard the crackling sound of flames. She broke through the ceiling that had fallen on top of her, and in a panic and ran from the building. Her work pants came off as she ran, so she continued in just her underwear. Once outside, she sought the help of a passing soldier and fled to the north in bare feet for her life.

People with burns were walking in droves along the Hakushima line of the streetcar tracks. She passed the Sentei (now Shukkeien Garden) and moved farther to the Kyobashi River, which flowed swifter than usual. She waded across the river by holding onto a raft of sorts, avoiding as much as possible the bodies floating in the water. After spending the night at her friend’s home, she headed to her uncle’s place in Fukawa (now part of Asakita Ward). Ms. Takenaga and her uncle began searching for her family the following day.

Ms. Takenaga found her father at Tsuruhane Shrine (now in Higashi Ward) one week after the bombing, and learned of the death of her sister, Takako, 16, a first-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin Vocational School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin University). Her father and two sisters were at home when the atomic bomb was dropped. Although they managed to escape to Sentei, Takako died there and her body removed without her father’s knowledge.

Another sister, Teruko, 12, a first-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin High School, was found at an evacuation center in Oko National School (now Oko Elementary School). She was exposed to the bomb when helping demolish buildings to create fire lanes in Zakoba-cho, located about one kilometer from the hypocenter. When they found her, Teruko was on the verge of death. Her burnt body, infested with maggots. All Ms. Takenaga could do was to stay close to her and shoo away flies with a fan.

On August 23, eight days after the end of the war, Teruko bled from her nose and ears and passed away. “She was just an innocent girl. It’s so cruel she died like this,” Ms. Takenaga said painfully.

She later heard her classmate who was tearfully crying for help at the Hiroshima Finance Bureau was unable to escape and was engulfed in flames. The ashes of Ms. Takenaga’s mother, who was also at home during the bombing, were never found. The surviving members of the family rested at Santaro’s parents’ house in Obayashi (now part of Asakita Ward). There, they were laid up with high fever, and their hair fell out.

“I will definitely return to Ebisu-cho,” said her father. And he did. Santaro went back to the ruins of his house by bicycle every day and built a shack on the site the following spring, later even reopening the antique shop. He served as president of the neighborhood association and was busily engaged in rebuilding Ebisu-cho until his death at the age of 66 in the fall of 1963.

About 20 years ago, Ms. Takenaga donated a watercolor painting in which her father depicted the catastrophe after the atomic bombing to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The museum has for a long time been collecting “drawings of the bombing made by survivors.” Ms. Takenaga said, “If nuclear weapons are dropped on earth now, the entirety of humankind would be destroyed. It’s my earnest desire that leaders of different countries make a firm peace agreement so as not to have war.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

I will pass her story to future generations

When Ms. Takenaga said painfully, “Teruko was an innocent girl and does not deserve to die like this,” I imagined her 74 years ago with frustrated look on her face, staying by her sister. I also would have been regretful; wondering what I could have done if I faced my sister’s tragic end. Ms. Takenaga asked us to “pass down the story to future generations.” I will keep her words in my mind and become one of those who convey her message. (Chihiro Yamase, 12)

I will carefully observe the world situation

Ms. Takenaga said, “I was brainwashed into believing that everything was for the sake of the country,” and felt “ashamed not to have been injured” after the atomic bombing. I was shocked and scared by what she said. Now, we can collect all sorts of information on our own. I want to observe the world situation carefully, know what’s right, and continually engage in as many peace activities as possible. (Hitoha Katsura, 15)

(Originally published on September 10, 2019)

Kiyoko Takenaga, 88, lost her mother and two sisters because of the atomic bomb. She still resides in the area where she was born and raised. She has a lot of memories of time spent with her family in the area. The area, Ebisu-cho (now Horikawa-cho in Naka Ward, Hiroshima), was a bustling shopping district lined with dress shops and movie theaters, prior to the war. Despite the destruction that occurred, her family remained there; Ms. Takenaga’s father tenaciously rebuilding their home on the site where their former house once stood.

In August of 1945, there were six in her family: her father Santaro (then 48), mother Shin (43), an older sister, two younger sisters and Ms. Takenaga herself. Santaro had previously run a signboard shop in front of the Ebisu Shrine, while also painting store signs and a theater marquee. Around 1940, he changed jobs and became an antique dealer. He was ahead of the times, wearing fashionable clothes, and quick to adopt new technology—for example, obtaining a radio and a phonograph before anyone else.

On August 6, 1945, Ms. Takenaga, then a third-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin High School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin Junior & Senior High School), was working as a mobilized student at the Hiroshima Finance Bureau in Hatchobori (now part of Naka Ward). She sat down at her desk at 8:00 a.m. Not long after, she saw a very bright yellow flash of light and was knocked from her seat.

The Bureau was located about 800 meters from the hypocenter. The ceiling above her in the Bureau’s two-story wooden building collapsed, and the area went completely dark. Ms. Takenaga managed to escape injury by getting under the desk, but her classmate who sat in front of her seemed to have been pinned beneath something. “Mother, help me. Oh God! Help me.” Ms. Takenaga heard her tearful voice calling.

She then heard the crackling sound of flames. She broke through the ceiling that had fallen on top of her, and in a panic and ran from the building. Her work pants came off as she ran, so she continued in just her underwear. Once outside, she sought the help of a passing soldier and fled to the north in bare feet for her life.

People with burns were walking in droves along the Hakushima line of the streetcar tracks. She passed the Sentei (now Shukkeien Garden) and moved farther to the Kyobashi River, which flowed swifter than usual. She waded across the river by holding onto a raft of sorts, avoiding as much as possible the bodies floating in the water. After spending the night at her friend’s home, she headed to her uncle’s place in Fukawa (now part of Asakita Ward). Ms. Takenaga and her uncle began searching for her family the following day.

Ms. Takenaga found her father at Tsuruhane Shrine (now in Higashi Ward) one week after the bombing, and learned of the death of her sister, Takako, 16, a first-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin Vocational School (now Hiroshima Jogakuin University). Her father and two sisters were at home when the atomic bomb was dropped. Although they managed to escape to Sentei, Takako died there and her body removed without her father’s knowledge.

Another sister, Teruko, 12, a first-year student at Hiroshima Jogakuin High School, was found at an evacuation center in Oko National School (now Oko Elementary School). She was exposed to the bomb when helping demolish buildings to create fire lanes in Zakoba-cho, located about one kilometer from the hypocenter. When they found her, Teruko was on the verge of death. Her burnt body, infested with maggots. All Ms. Takenaga could do was to stay close to her and shoo away flies with a fan.

On August 23, eight days after the end of the war, Teruko bled from her nose and ears and passed away. “She was just an innocent girl. It’s so cruel she died like this,” Ms. Takenaga said painfully.

She later heard her classmate who was tearfully crying for help at the Hiroshima Finance Bureau was unable to escape and was engulfed in flames. The ashes of Ms. Takenaga’s mother, who was also at home during the bombing, were never found. The surviving members of the family rested at Santaro’s parents’ house in Obayashi (now part of Asakita Ward). There, they were laid up with high fever, and their hair fell out.

“I will definitely return to Ebisu-cho,” said her father. And he did. Santaro went back to the ruins of his house by bicycle every day and built a shack on the site the following spring, later even reopening the antique shop. He served as president of the neighborhood association and was busily engaged in rebuilding Ebisu-cho until his death at the age of 66 in the fall of 1963.

About 20 years ago, Ms. Takenaga donated a watercolor painting in which her father depicted the catastrophe after the atomic bombing to Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum. The museum has for a long time been collecting “drawings of the bombing made by survivors.” Ms. Takenaga said, “If nuclear weapons are dropped on earth now, the entirety of humankind would be destroyed. It’s my earnest desire that leaders of different countries make a firm peace agreement so as not to have war.”

Teenagers’ Impressions

I will pass her story to future generations

When Ms. Takenaga said painfully, “Teruko was an innocent girl and does not deserve to die like this,” I imagined her 74 years ago with frustrated look on her face, staying by her sister. I also would have been regretful; wondering what I could have done if I faced my sister’s tragic end. Ms. Takenaga asked us to “pass down the story to future generations.” I will keep her words in my mind and become one of those who convey her message. (Chihiro Yamase, 12)

I will carefully observe the world situation

Ms. Takenaga said, “I was brainwashed into believing that everything was for the sake of the country,” and felt “ashamed not to have been injured” after the atomic bombing. I was shocked and scared by what she said. Now, we can collect all sorts of information on our own. I want to observe the world situation carefully, know what’s right, and continually engage in as many peace activities as possible. (Hitoha Katsura, 15)

(Originally published on September 10, 2019)