Survivors’ Stories: Satoru Arai, 84, Hiroshima: Owner of burnt shirt on display at museum describes A-bomb experience to visitors

Nov. 4, 2019

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

The United States is also my homeland

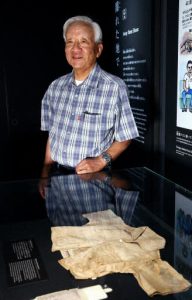

A small American-made shirt is on display at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in a new section about A-bomb victims and survivors of other nationalities. The shirt belonged to Satoru Arai, 84, who was wearing it on the day of the atomic bombing. Mr. Arai was born in the United States, but was then raised in Hiroshima. After growing up here, he returned to America.

The black letters of the name tag that was sewn onto the shirt, on the left side of the chest, are burnt, and burn marks have also remained on the sleeve. Mr. Arai sometimes stands next to the shirt and, as one of the “Hiroshima Peace Volunteers,” provides explanations about the shirt to visitors. He said, “When I tell them that this shirt was mine, everyone is surprised because they can’t imagine that the owner could still be alive.”

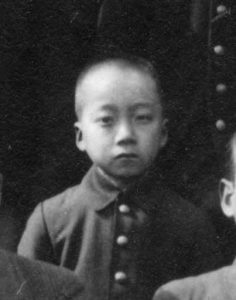

Mr. Arai was born in 1935 in Honolulu, Hawaii, where his grandparents had immigrated. But when he was three years old, his family moved to Hiroshima. The Sino-Japanese War had broken out in the previous year, and relations between the United States and Japan were beginning to deteriorate.

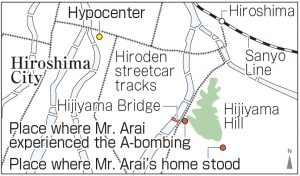

When Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb, Mr. Arai was in fifth grade at Oko National School (now Oko Elementary School). On the morning of August 6, 1945, he and his grandmother were at the east end of Hijiyama Bridge, picking up pieces of scrap wood from houses that had been torn down to create a fire lane. Suddenly, it felt like he saw a flash of white light in front of him. At the same time, the earth tremored beneath him, and he was blown off his feet. He lost consciousness.

He was at a location 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. When he came to, he found dirt, dust, and soot swirling in the air and there was darkness all around him. When he managed to make it back to his home in Deshio-cho (now part of Minami Ward), his mother cried, “What happened to you?” His cheeks, arms, and right leg were burnt and swollen, and the skin had peeled away and was exposing his flesh.

When he, his mother, and his three-year-old brother fled to an air-raid shelter at Hijiyama Hill, they found that it was packed with people who were injured. His cheek began to tingle with pain and, when he touched it, his fingers slipped on the peeling skin. Fumio, his father, hurried from where he was working, at the Hiroshima Army Ordnance Supply Depot, and applied cooking oil to Mr. Arai’s wounds.

Misao was pregnant at the time, and had reached seven months, but the baby was born dead during the chaotic conditions of the aftermath of the atomic bombing. Because of his severe burns, Mr. Arai wasn’t able to leave his bed for two months. Whenever his mother sought to treat his burns with Mercurochrome or an antibiotic ointment that his father had purchased from a pharmacy on the outskirts of the city, he screamed from the intense pain.

After the war ended, he graduated from high school and worked at the Hiroshima Prefectural Office. When he was 21, he returned to the United States, the country where he was born, dreaming of a more prosperous life. He earned a living by working as a gardener in the suburbs of Los Angeles. Later, he ran an auto repair shop. At first, he wore long-sleeved shirts to hide the keloids on his arm, but then gradually started to wear short-sleeved shirts. Looking back on those days, he said with frustration, “When someone would ask about the scars on my body and I told them that it was because of the atomic bomb, some of them would apologize, but others would mention Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.”

Costs for medical care in the United States are very high. Moreover, American doctors have little knowledge of the health problems faced by the survivors as a result of their experience of the atomic bombing. In 1965, he and his colleagues formed a group for A-bomb survivors. In 1974, he served as chair of the Committee of Atomic Bomb Survivors, and called on the U.S. government and the California state government to pass legislation for an A-bomb survivors relief law. He worked together on this with the late Kazu Sueishi, who died two years ago at the age of 90.

Mr. Arai said, “All the documents we submitted were rejected. The government wouldn’t listen at all to anything related to the atomic bombing.” Despite such circumstances, Hiroshima Prefecture began to send a group of doctors to the United States in 1977. Since then, Japanese doctors have conducted health check-ups for survivors living in America every other year. Mr. Arai left the United States about 30 years ago and again resides in Hiroshima.

He became a volunteer guide for the museum in 2007, as he wanted to share his A-bomb experience with visitors by making use of his English ability. These days, though, little progress is being made in nuclear disarmament efforts in the world, including in the United States, his second homeland. He said, “Once someone presses a button of a nuclear weapon, it will be all over, regardless of one’s nation or race. I hope that the leaders of nations will be made aware of the fact that the use of nuclear weapons is a suicidal act.” Standing alongside his old shirt at the museum, like his divided soul, he will continue doing his best to convey the damage caused by the atomic bombing to visitors from all over the world.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I felt a heavy responsibility to help hand down the survivors’ experiences

In front of Mr. Arai’s old shirt, now on display in the section of the Peace Memorial Museum about foreign nationals who experienced the atomic bombing, we heard his A-bomb account first-hand. There was a big hole on the left shoulder of his shirt. I could clearly imagine the scene on that day, and I was hit by the fact that people who weren’t Japanese were also victims and survivors of the bombing. His shirt helped us understand his desire for peace directly, and I felt a heavy responsibility to help hand down the experiences of the survivors to the following generations. (Yukiho Saito, 17)

I was impressed by his courage in not hiding his keloids

Mr. Arai showed us the keloid scars on his face and his arm. It was the first time for me to see actual keloids. They looked very painful and made my heart ache. I felt horrified when he told us that he, just three years younger than me at that time, cried out in pain while his burns were being treated. I think it takes a lot of courage for him not to hide his keloids. I would like many other people to listen to Mr. Arai’s experience, too. (Shino Taguchi, 13)

(Originally published on November 4, 2019)

The United States is also my homeland

A small American-made shirt is on display at the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum in a new section about A-bomb victims and survivors of other nationalities. The shirt belonged to Satoru Arai, 84, who was wearing it on the day of the atomic bombing. Mr. Arai was born in the United States, but was then raised in Hiroshima. After growing up here, he returned to America.

The black letters of the name tag that was sewn onto the shirt, on the left side of the chest, are burnt, and burn marks have also remained on the sleeve. Mr. Arai sometimes stands next to the shirt and, as one of the “Hiroshima Peace Volunteers,” provides explanations about the shirt to visitors. He said, “When I tell them that this shirt was mine, everyone is surprised because they can’t imagine that the owner could still be alive.”

Mr. Arai was born in 1935 in Honolulu, Hawaii, where his grandparents had immigrated. But when he was three years old, his family moved to Hiroshima. The Sino-Japanese War had broken out in the previous year, and relations between the United States and Japan were beginning to deteriorate.

When Hiroshima was attacked with the atomic bomb, Mr. Arai was in fifth grade at Oko National School (now Oko Elementary School). On the morning of August 6, 1945, he and his grandmother were at the east end of Hijiyama Bridge, picking up pieces of scrap wood from houses that had been torn down to create a fire lane. Suddenly, it felt like he saw a flash of white light in front of him. At the same time, the earth tremored beneath him, and he was blown off his feet. He lost consciousness.

He was at a location 1.7 kilometers from the hypocenter. When he came to, he found dirt, dust, and soot swirling in the air and there was darkness all around him. When he managed to make it back to his home in Deshio-cho (now part of Minami Ward), his mother cried, “What happened to you?” His cheeks, arms, and right leg were burnt and swollen, and the skin had peeled away and was exposing his flesh.

When he, his mother, and his three-year-old brother fled to an air-raid shelter at Hijiyama Hill, they found that it was packed with people who were injured. His cheek began to tingle with pain and, when he touched it, his fingers slipped on the peeling skin. Fumio, his father, hurried from where he was working, at the Hiroshima Army Ordnance Supply Depot, and applied cooking oil to Mr. Arai’s wounds.

Misao was pregnant at the time, and had reached seven months, but the baby was born dead during the chaotic conditions of the aftermath of the atomic bombing. Because of his severe burns, Mr. Arai wasn’t able to leave his bed for two months. Whenever his mother sought to treat his burns with Mercurochrome or an antibiotic ointment that his father had purchased from a pharmacy on the outskirts of the city, he screamed from the intense pain.

After the war ended, he graduated from high school and worked at the Hiroshima Prefectural Office. When he was 21, he returned to the United States, the country where he was born, dreaming of a more prosperous life. He earned a living by working as a gardener in the suburbs of Los Angeles. Later, he ran an auto repair shop. At first, he wore long-sleeved shirts to hide the keloids on his arm, but then gradually started to wear short-sleeved shirts. Looking back on those days, he said with frustration, “When someone would ask about the scars on my body and I told them that it was because of the atomic bomb, some of them would apologize, but others would mention Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.”

Costs for medical care in the United States are very high. Moreover, American doctors have little knowledge of the health problems faced by the survivors as a result of their experience of the atomic bombing. In 1965, he and his colleagues formed a group for A-bomb survivors. In 1974, he served as chair of the Committee of Atomic Bomb Survivors, and called on the U.S. government and the California state government to pass legislation for an A-bomb survivors relief law. He worked together on this with the late Kazu Sueishi, who died two years ago at the age of 90.

Mr. Arai said, “All the documents we submitted were rejected. The government wouldn’t listen at all to anything related to the atomic bombing.” Despite such circumstances, Hiroshima Prefecture began to send a group of doctors to the United States in 1977. Since then, Japanese doctors have conducted health check-ups for survivors living in America every other year. Mr. Arai left the United States about 30 years ago and again resides in Hiroshima.

He became a volunteer guide for the museum in 2007, as he wanted to share his A-bomb experience with visitors by making use of his English ability. These days, though, little progress is being made in nuclear disarmament efforts in the world, including in the United States, his second homeland. He said, “Once someone presses a button of a nuclear weapon, it will be all over, regardless of one’s nation or race. I hope that the leaders of nations will be made aware of the fact that the use of nuclear weapons is a suicidal act.” Standing alongside his old shirt at the museum, like his divided soul, he will continue doing his best to convey the damage caused by the atomic bombing to visitors from all over the world.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I felt a heavy responsibility to help hand down the survivors’ experiences

In front of Mr. Arai’s old shirt, now on display in the section of the Peace Memorial Museum about foreign nationals who experienced the atomic bombing, we heard his A-bomb account first-hand. There was a big hole on the left shoulder of his shirt. I could clearly imagine the scene on that day, and I was hit by the fact that people who weren’t Japanese were also victims and survivors of the bombing. His shirt helped us understand his desire for peace directly, and I felt a heavy responsibility to help hand down the experiences of the survivors to the following generations. (Yukiho Saito, 17)

I was impressed by his courage in not hiding his keloids

Mr. Arai showed us the keloid scars on his face and his arm. It was the first time for me to see actual keloids. They looked very painful and made my heart ache. I felt horrified when he told us that he, just three years younger than me at that time, cried out in pain while his burns were being treated. I think it takes a lot of courage for him not to hide his keloids. I would like many other people to listen to Mr. Arai’s experience, too. (Shino Taguchi, 13)

(Originally published on November 4, 2019)