Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, Part 2: Government reluctant to grasp overall picture of damage

Nov. 30, 2019

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

Concern over war responsibility and compensation?

Until the spring of this year, four of the five members of the family of Nobuyoshi Aoki and his wife Fumi had not been included in the data compiled by the City of Hiroshima from its survey of the victims of the atomic bombing. Hisayuki Aoki, 73, Nobuyoshi’s nephew, said while gazing at a memorial monument which stands at his home in Toyama City, “I had long believed that all the names of the Aoki family were included in records of some kind.”

The fact that the names were missing only came to light when Machiko Kanai, 66, Nobuyoshi’s niece, asked the City of Hiroshima to search for the Aoki family names in the register of the A-bomb victims. She said, “If I had not thought of checking their names when I went on a sightseeing trip to Hiroshima three years ago…”

Currently, the city’s work of obtaining the names of A-bomb victims depends solely on bereaved family members submitting an official application to add the name of the deceased person into the register of the A-bomb victims. However, looking at the history of the A-bomb damage survey, it is apparent that the city did engage in registration efforts.

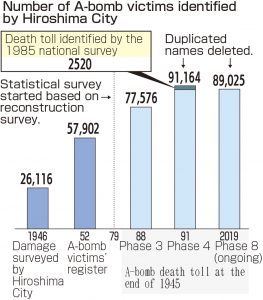

In 1946, the year after the atomic bombing, the City of Hiroshima initiated an investigation into the death toll with help from the heads of neighborhood associations and various other organizations. However, due to the utter destruction of local communities at that time, the names of just 26,116 dead and missing could be identified. In 1951, when the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims was being constructed, the city asked citizens to provide information about their deceased family members, among others, in order to create the register of the A-bomb victims. In 1952, when the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims was completed, the first volumes of the register, which were placed in the stone chest beneath the Cenotaph, contained 57,902 names. At that time, it was difficult for the city to expand these registration efforts on a nationwide scale.

Joint reconstruction study involving government and citizens

A large scale joint study was also conducted that involved government and citizens. In the late 1960s, Hiroshima University and various other organizations launched a Reconstruction Study. They created a house-to-house map that reproduced the former streetscape of the hypocenter area which was completely destroyed by the atomic bomb. It was an attempt to create detailed records of the damage caused to each household. To do this, the former residents of the area gathered together, tried their best to remember as much as they could, then sought to confirm these memories. Backed by this momentum, the City of Hiroshima also began a study whose scope was expanded to an area within a two-kilometer radius of the hypocenter.

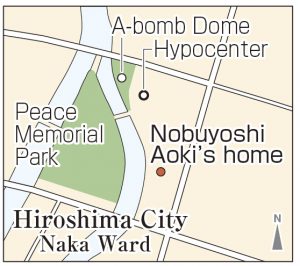

The home of the Aoki family, which had been located at 3-chome in the former Otemachi district, was close enough to the hypocenter to be included in the scope of the study. There were, however, no former residents who knew about the family in detail because they had moved into the area only just before the end of the war.

Through the course of their efforts, the study team reproduced 95% or more of the area within a radius of 500 meters of the hypocenter in the form of a map, and was able to ascertain the damage caused to about 2,400 households, or about 80 percent of the households surveyed. This was due to the efforts of the citizens who participated in the study. However, there were families in which all the members died or in which many of the members died and those who survived left Hiroshima as a result. These families were designated as “missing.”

“I sincerely hope that a nationwide study will be carried out as soon as possible. … I emphasize that the study will only succeed with an enormous amount of understanding on the part of the government authorities and adequate help from the public, including A-bomb survivors,” said the late Kiyoshi Shimizu, a Hiroshima University professor who led the reconstruction study. The report prepared by Professor Shimizu and his colleagues, published in 1978, conveys their chagrin.

Government explained that the study was a complement

Meanwhile, the Japanese government was always reluctant to conduct a study of the A-bomb victims. One reason for this was that, after the war, Japan was occupied and controlled by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ), led by the United States military, which had dropped the atomic bombs on Japan. Even after Japan regained its independence in 1952, however, the government did not seek to initiate a study.

It wasn’t until 1985, 40 years after the atomic bombings, that the Japanese government embarked on a nationwide study of the holders of the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate (about 360,000 people at that time) living in Japan, after repeated requests from the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to do so. The study asked A-bomb survivors whether they had family members, relatives, or friends who had died due to the atomic bombing and its related diseases. Hisayuki Aoki, the bereaved relative of the family in which all of its members perished, did not receive a questionnaire.

In those days, the national government explained that its survey was merely complementing the study conducted by the City of Hiroshima and various other organizations. It was said that the more the government proactively carried out such surveys to clarify the damage, the greater the possibility that demands would be made on the government to investigate issues involving war responsibility and damage compensation. The government was believed to have been afraid of a groundswell that would start in the A-bombed cities and spread to incendiary bomb victims throughout the entire country.

The results of the survey, which were far from the expected results of a nationwide survey, found that 5,551 died due to the atomic bombing in Hiroshima, and 2,520 of these died before the end of 1945. Their names were added to the register of the A-bomb victims in 1990. The reason why only Nobuyoshi’s name had been registered when Ms. Kanai made an inquiry to the City of Hiroshima is probably due to former military personnel having responded to the government survey.

(Originally published on November 30, 2019)

Concern over war responsibility and compensation?

Until the spring of this year, four of the five members of the family of Nobuyoshi Aoki and his wife Fumi had not been included in the data compiled by the City of Hiroshima from its survey of the victims of the atomic bombing. Hisayuki Aoki, 73, Nobuyoshi’s nephew, said while gazing at a memorial monument which stands at his home in Toyama City, “I had long believed that all the names of the Aoki family were included in records of some kind.”

The fact that the names were missing only came to light when Machiko Kanai, 66, Nobuyoshi’s niece, asked the City of Hiroshima to search for the Aoki family names in the register of the A-bomb victims. She said, “If I had not thought of checking their names when I went on a sightseeing trip to Hiroshima three years ago…”

Currently, the city’s work of obtaining the names of A-bomb victims depends solely on bereaved family members submitting an official application to add the name of the deceased person into the register of the A-bomb victims. However, looking at the history of the A-bomb damage survey, it is apparent that the city did engage in registration efforts.

In 1946, the year after the atomic bombing, the City of Hiroshima initiated an investigation into the death toll with help from the heads of neighborhood associations and various other organizations. However, due to the utter destruction of local communities at that time, the names of just 26,116 dead and missing could be identified. In 1951, when the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims was being constructed, the city asked citizens to provide information about their deceased family members, among others, in order to create the register of the A-bomb victims. In 1952, when the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims was completed, the first volumes of the register, which were placed in the stone chest beneath the Cenotaph, contained 57,902 names. At that time, it was difficult for the city to expand these registration efforts on a nationwide scale.

Joint reconstruction study involving government and citizens

A large scale joint study was also conducted that involved government and citizens. In the late 1960s, Hiroshima University and various other organizations launched a Reconstruction Study. They created a house-to-house map that reproduced the former streetscape of the hypocenter area which was completely destroyed by the atomic bomb. It was an attempt to create detailed records of the damage caused to each household. To do this, the former residents of the area gathered together, tried their best to remember as much as they could, then sought to confirm these memories. Backed by this momentum, the City of Hiroshima also began a study whose scope was expanded to an area within a two-kilometer radius of the hypocenter.

The home of the Aoki family, which had been located at 3-chome in the former Otemachi district, was close enough to the hypocenter to be included in the scope of the study. There were, however, no former residents who knew about the family in detail because they had moved into the area only just before the end of the war.

Through the course of their efforts, the study team reproduced 95% or more of the area within a radius of 500 meters of the hypocenter in the form of a map, and was able to ascertain the damage caused to about 2,400 households, or about 80 percent of the households surveyed. This was due to the efforts of the citizens who participated in the study. However, there were families in which all the members died or in which many of the members died and those who survived left Hiroshima as a result. These families were designated as “missing.”

“I sincerely hope that a nationwide study will be carried out as soon as possible. … I emphasize that the study will only succeed with an enormous amount of understanding on the part of the government authorities and adequate help from the public, including A-bomb survivors,” said the late Kiyoshi Shimizu, a Hiroshima University professor who led the reconstruction study. The report prepared by Professor Shimizu and his colleagues, published in 1978, conveys their chagrin.

Government explained that the study was a complement

Meanwhile, the Japanese government was always reluctant to conduct a study of the A-bomb victims. One reason for this was that, after the war, Japan was occupied and controlled by the General Headquarters of the Allied Powers (GHQ), led by the United States military, which had dropped the atomic bombs on Japan. Even after Japan regained its independence in 1952, however, the government did not seek to initiate a study.

It wasn’t until 1985, 40 years after the atomic bombings, that the Japanese government embarked on a nationwide study of the holders of the Atomic Bomb Survivor’s Certificate (about 360,000 people at that time) living in Japan, after repeated requests from the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki to do so. The study asked A-bomb survivors whether they had family members, relatives, or friends who had died due to the atomic bombing and its related diseases. Hisayuki Aoki, the bereaved relative of the family in which all of its members perished, did not receive a questionnaire.

In those days, the national government explained that its survey was merely complementing the study conducted by the City of Hiroshima and various other organizations. It was said that the more the government proactively carried out such surveys to clarify the damage, the greater the possibility that demands would be made on the government to investigate issues involving war responsibility and damage compensation. The government was believed to have been afraid of a groundswell that would start in the A-bombed cities and spread to incendiary bomb victims throughout the entire country.

The results of the survey, which were far from the expected results of a nationwide survey, found that 5,551 died due to the atomic bombing in Hiroshima, and 2,520 of these died before the end of 1945. Their names were added to the register of the A-bomb victims in 1990. The reason why only Nobuyoshi’s name had been registered when Ms. Kanai made an inquiry to the City of Hiroshima is probably due to former military personnel having responded to the government survey.

(Originally published on November 30, 2019)