Striving to fill voids in Hiroshima, Part 3: Small victims of the bombing

Dec. 1, 2019

by Kyosuke Mizukawa, Staff Writer

Newborn lived only hours, never had a name

As a result of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Nobuyoshi Aoki and his entire family lost their lives. Hisayuki Aoki, 73, a resident of Toyama City, is Nobuyoshi’s nephew. Hisayuki heard his late father, Katsuji Aoki, make only one comment about Nobuyoshi’s family. Katusji told him, “It seems that the baby boy was with his mother at the time of the bombing, but the baby’s remains were never found, despite the efforts that were made.”

The baby was Nobumi Aoki, Nobuyoshi’s son. He was only 9 months old at the time. Yoshimi Aoki, Nobuyoshi’s daughter, who was four, also perished.

Some victims are missing from documents

The City of Hiroshima has gathered information about victims of the atomic bombing not only from the register of the A-bomb victims and data from past public surveys, but also lists of the dead compiled by schools and companies. However, as the case of Nobuyoshi’s two children illustrate, in that they were not included in such records until just recently, the names of very young victims of the A-bomb attack, like newborns and preschool-age children, were often missing from these documents.

One newborn, a baby girl, died on the same day she was born as a consequence of the atomic bombing. The Chugoku Shimbun visited one of her relatives.

“The baby wasn’t even given a name,” said Yaeko Maeda, 69. Ms. Maeda’s father, Minoru Okino, spoke frequently about the children he lost at the time of the atomic bombing. He died in 1991 at the age of 80.

Minoru’s original family name was Kubota. He was a second-generation Japanese American who was born in a family of Japanese immigrants in the U.S. state of Hawaii. He then married and had a family in Hiroshima, where his grandparents lived. In the early morning of August 6, 1945, Tsuyako Kubota, 25 at the time, gave birth to their second daughter at their home in Nishikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward). Minoru prepared hot water for the newborn’s first bath, and diapers, and he was present for the delivery.

Soon after Minoru stepped outside to see off the midwife, the atomic bomb exploded in the sky above Hiroshima. Tsuyako, their eldest daughter Sumie, who was two, and their second baby daughter, became trapped under the wreckage of their house.

Minoru later left notes about his experience, writing, “I tried so hard to get them out and my hands became bloody. But I couldn’t do it.” With fire approaching, the only thing he could do was flee with his son, who was at a neighbor’s house. He also wrote, “Sumie was crying. She said to me, ‘Daddy, it’s hot! The fire is coming! My hands are burning!’ There was a final scream, and then I couldn’t hear her voice anymore.”

After the war, he got remarried and raised his son and two daughters, including Ms. Maeda, who were born in the post-war years. Almost every month, they would pay a visit to the family grave. The death of the baby girl, who was alive for only a few hours and lost her life before she was given a name, was inscribed on the gravestone with the words “Died due to the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945 at the age of zero.”

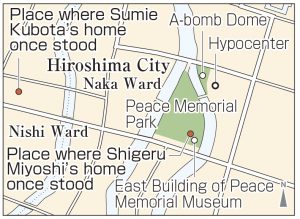

Ms. Maeda said, “She had such a pitiful fate. So I wondered if it was possible to preserve some evidence of her life.” Thinking of the sorrow that her father had carried with him until his death, she visited the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, located in Naka Ward, which handles the registration and disclosure of the names of the A-bomb victims. The staff there understood Ms. Maeda’s wish and registered Minoru’s second daughter as one of the victims. In this registration, her first name has been left blank and only her family name, “Kubota,” which was Minoru’s family name at the time, is written.

Death of pregnant woman counted as “single victim”

As for adding the baby’s name to the register of the A-bomb victims, which is stored within the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in the Peace Memorial Park, Ms. Maeda hasn’t submitted an application for this because she thinks it would be difficult. The city’s Survey of Victims of the Atomic Bombing is based on confirmation of the full name of each victim. It is fairly certain that Minoru’s second daughter is missing in the number of victims, 89,025, that were identified as a result of the survey.

In fact, the atomic bombing killed not only newborn babies like “Ms. Kubota” but also babies that were waiting to be born.

The Peace Memorial Museum holds a drawing of the atomic bombing that depicts the burnt body of a pregnant woman with a stomach band still around her middle. The late Shigeru Miyoshi drew the picture to remember his wife Yoshiko, who was then 37. He found her remains in the ruins of his home, which had stood in the current area of the Peace Memorial Park, on the day after the bombing.

Miyoko Doi, 90, Mr. Miyoshi’s eldest daughter and a resident of Asakita Ward, said in a choked voice, “Such a tragic thing should never ever happen.” According to the city, deaths like Yoshiko’s were counted as a “single victim” in the survey.

(Originally published on December 1, 2019)

Newborn lived only hours, never had a name

As a result of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima, Nobuyoshi Aoki and his entire family lost their lives. Hisayuki Aoki, 73, a resident of Toyama City, is Nobuyoshi’s nephew. Hisayuki heard his late father, Katsuji Aoki, make only one comment about Nobuyoshi’s family. Katusji told him, “It seems that the baby boy was with his mother at the time of the bombing, but the baby’s remains were never found, despite the efforts that were made.”

The baby was Nobumi Aoki, Nobuyoshi’s son. He was only 9 months old at the time. Yoshimi Aoki, Nobuyoshi’s daughter, who was four, also perished.

Some victims are missing from documents

The City of Hiroshima has gathered information about victims of the atomic bombing not only from the register of the A-bomb victims and data from past public surveys, but also lists of the dead compiled by schools and companies. However, as the case of Nobuyoshi’s two children illustrate, in that they were not included in such records until just recently, the names of very young victims of the A-bomb attack, like newborns and preschool-age children, were often missing from these documents.

One newborn, a baby girl, died on the same day she was born as a consequence of the atomic bombing. The Chugoku Shimbun visited one of her relatives.

“The baby wasn’t even given a name,” said Yaeko Maeda, 69. Ms. Maeda’s father, Minoru Okino, spoke frequently about the children he lost at the time of the atomic bombing. He died in 1991 at the age of 80.

Minoru’s original family name was Kubota. He was a second-generation Japanese American who was born in a family of Japanese immigrants in the U.S. state of Hawaii. He then married and had a family in Hiroshima, where his grandparents lived. In the early morning of August 6, 1945, Tsuyako Kubota, 25 at the time, gave birth to their second daughter at their home in Nishikanon-machi (now part of Nishi Ward). Minoru prepared hot water for the newborn’s first bath, and diapers, and he was present for the delivery.

Soon after Minoru stepped outside to see off the midwife, the atomic bomb exploded in the sky above Hiroshima. Tsuyako, their eldest daughter Sumie, who was two, and their second baby daughter, became trapped under the wreckage of their house.

Minoru later left notes about his experience, writing, “I tried so hard to get them out and my hands became bloody. But I couldn’t do it.” With fire approaching, the only thing he could do was flee with his son, who was at a neighbor’s house. He also wrote, “Sumie was crying. She said to me, ‘Daddy, it’s hot! The fire is coming! My hands are burning!’ There was a final scream, and then I couldn’t hear her voice anymore.”

After the war, he got remarried and raised his son and two daughters, including Ms. Maeda, who were born in the post-war years. Almost every month, they would pay a visit to the family grave. The death of the baby girl, who was alive for only a few hours and lost her life before she was given a name, was inscribed on the gravestone with the words “Died due to the atomic bombing on August 6, 1945 at the age of zero.”

Ms. Maeda said, “She had such a pitiful fate. So I wondered if it was possible to preserve some evidence of her life.” Thinking of the sorrow that her father had carried with him until his death, she visited the Hiroshima National Peace Memorial Hall for the Atomic Bomb Victims, located in Naka Ward, which handles the registration and disclosure of the names of the A-bomb victims. The staff there understood Ms. Maeda’s wish and registered Minoru’s second daughter as one of the victims. In this registration, her first name has been left blank and only her family name, “Kubota,” which was Minoru’s family name at the time, is written.

Death of pregnant woman counted as “single victim”

As for adding the baby’s name to the register of the A-bomb victims, which is stored within the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims in the Peace Memorial Park, Ms. Maeda hasn’t submitted an application for this because she thinks it would be difficult. The city’s Survey of Victims of the Atomic Bombing is based on confirmation of the full name of each victim. It is fairly certain that Minoru’s second daughter is missing in the number of victims, 89,025, that were identified as a result of the survey.

In fact, the atomic bombing killed not only newborn babies like “Ms. Kubota” but also babies that were waiting to be born.

The Peace Memorial Museum holds a drawing of the atomic bombing that depicts the burnt body of a pregnant woman with a stomach band still around her middle. The late Shigeru Miyoshi drew the picture to remember his wife Yoshiko, who was then 37. He found her remains in the ruins of his home, which had stood in the current area of the Peace Memorial Park, on the day after the bombing.

Miyoko Doi, 90, Mr. Miyoshi’s eldest daughter and a resident of Asakita Ward, said in a choked voice, “Such a tragic thing should never ever happen.” According to the city, deaths like Yoshiko’s were counted as a “single victim” in the survey.

(Originally published on December 1, 2019)