Survivors’ Stories: Shizuko Abe, 92, Hiroshima: She suffered terrible burns but defied discrimination

Jan. 13, 2020

by Miho Kuwajima, Staff Writer

Shizuko Abe (née Dairiki) experienced the atomic bombing and suffered terrible burns to her face and hands when she was 18 years old. Looking back on half a life completely changed by the atomic bombing, she said, “I’m living witness to the effects of the atomic bombing.” While raising three children, she has made anti-nuclear appeals and continued to share her A-bomb experience after overcoming its aftereffects and personal discrimination.

Ms. Abe was raised in a farming family in Kaita-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture. After she graduated from Yasuda Girls’ High School (now Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School and High School), she married Saburo Abe, who had been a soldier, at the age of 17. They began their married life, separated, as Saburo was dispatched to Manchuria (in northeastern China) and the southern front. While they were living like this, the day of the atomic bombing came.

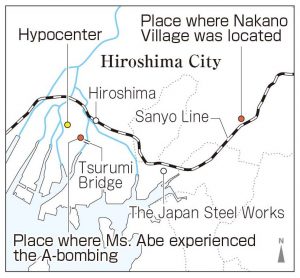

The morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Abe was helping to tear down homes to create a fire lane in Hiratsuka-cho (now part of Naka Ward) with people in Nakano Village (now part of Aki Ward), where she was living with her mother-in-law. When she was carrying out roofing tiles on the roof of a private home, she was suddenly blown about ten meters by the blast and knocked to the ground in the garden.

Ms. Abe was about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. When she came to, she found the area all around her was dim and there was a terrible smell of burning bodies. Because the right side of her body was exposed to the bomb’s heat rays, her face had become swollen, and the skin on her right arm was peeling off and dangling down from the tips of her nails. She felt the intense pain when she put her hand down, so she raised it over her chest and headed to Nakano Village on foot with her neighbors.

Ms. Abe was later taken in at a makeshift relief station of Japan Steel Works in Funakoshi-cho (now part of Aki Ward), and stayed there for three days. After that, she was reunited with her father and finally returned to her parents’ home. In the time that followed, her family grated potatoes and applied them to her wounds, using a piece of cloth of a yukata (an informal cotton kimono), in place of gauze. Her burns gradually became keloid scars, and her mouth remained twisted. The fingers of her right hand bent backward and became stiff, and she had difficulty leading daily life.

Saburo, who returned to Japan from his military service at the end of the year, was advised to get divorced by those around him, but refused, and decided to remain married to her for his whole life. The following year, when Ms. Abe became pregnant with her first son, she was in the hospital for six months and underwent skin graft surgery. She gave birth to her first son in November 1946, her second son in 1949, and her first daughter in 1954.

Even though she was loved by her husband, some people teased her, saying, “Red Ogre is walking” when she walked outdoors. Her son’s classmates bullied him, calling him, “A child of the atomic bombing.” He sometimes returned home using a mountain route to avoid being seen. Ms. Abe said, “I always lead my life with my head down and cried with my children. How again and again I wanted to die.”

A-bomb survivors encouraged her to take a step forward to advance. The late Kiyoshi Kikkawa, who was later referred to as “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1,” built a shack in front of the Atomic Bomb Dome. Ms. Abe shared her anxieties with people who gathered around the shack, and was deeply involved with early efforts to support A-bomb survivors. In 1956, she joined the group that submitted a petition appealing for support A-bomb survivors to the Diet with her 6-year-old second son. She wrote a poem, “Please put a warm hand, like sunlight at ten in the morning, / on survivors whose forgotten smiles lie somewhere in the distance / due to their grief and sorrow.” The poem was made into a song, and it was sung at anti-nuclear and other gatherings.

In 1964, Ms. Abe participated in the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Pilgrimage, planned by the late American peace activist Barbara Reynolds and others, and visited Europe, North America and the Soviet Union, talking about her experience for about three months. She also met with former President Harry S. Truman, who had ordered the A-bomb attacks. American people were kind to her, and she said the hatred she used to have had disappeared.

“I don’t want people to face the same kind of suffering,” said Ms. Abe. She intently continued talking about her A-bomb experience, but quit doing so about seven years ago. She now lives in a facility for the elderly. She feels she sowed seeds of peace, but can’t help feeling anger toward the Trump administration and the Japanese government that has followed in its footsteps. She said, “One atomic bomb did great damage. If another atomic bomb were used, the earth would be destroyed. How important peace is! I oppose the use and possession of nuclear weapons. I want you to speak about it all the time.” She feels so, even stronger, as we now see the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing coming.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I’ll always keep compassion in mind

When Ms. Abe was young, she suffered terrible discrimination, and people said, “Red Ogre is coming” when she was walking about town. If I were in her shoes, I would shut myself away at home and lose the courage to live my life. Ms. Abe said, “I want you to communicate with others with a kind heart and a soft look,” and I learned that if we acted with compassion, the small circle of peace would widen. I’ll communicate with my friends and family like that. (Yurina Yunoki, 16)

I want to make “flowers” of activity bloom

Ms. Abe compares the anti-nuclear movement and her speaking activities to flowers and stresses, “The seeds I sowed grew little by little.” However, if a nation’s leader talks about peace in word only and does not advance disarmament, the shoots that have grown will die. Ms. Abe decided to carry out her mission as an A-bomb survivor and continued to talk about her painful experience of the atomic bombing. With her thoughts, I want to convey the importance of a peaceful world in my own words and make flowers bloom. (Yuna Okajima, 15)

I’ll send the message about the importance of peace to the world

Ms. Abe told us how important peace was and asked us to keep saving the peace. I can not only set up a major goal, but also send a message of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima and of the importance of peace to the world, using the social networking service, among other means. For that purpose, I need to learn about the exact state of current Hiroshima, the A-bomb experiences, and A-bomb materials, and then send the message. I want to post my message one by one.(Hitoha Katsura, 15)

(Originally published on January 13, 2020)

Shizuko Abe (née Dairiki) experienced the atomic bombing and suffered terrible burns to her face and hands when she was 18 years old. Looking back on half a life completely changed by the atomic bombing, she said, “I’m living witness to the effects of the atomic bombing.” While raising three children, she has made anti-nuclear appeals and continued to share her A-bomb experience after overcoming its aftereffects and personal discrimination.

Ms. Abe was raised in a farming family in Kaita-cho, Hiroshima Prefecture. After she graduated from Yasuda Girls’ High School (now Yasuda Girls’ Junior High School and High School), she married Saburo Abe, who had been a soldier, at the age of 17. They began their married life, separated, as Saburo was dispatched to Manchuria (in northeastern China) and the southern front. While they were living like this, the day of the atomic bombing came.

The morning of August 6, 1945, Ms. Abe was helping to tear down homes to create a fire lane in Hiratsuka-cho (now part of Naka Ward) with people in Nakano Village (now part of Aki Ward), where she was living with her mother-in-law. When she was carrying out roofing tiles on the roof of a private home, she was suddenly blown about ten meters by the blast and knocked to the ground in the garden.

Ms. Abe was about 1.5 kilometers from the hypocenter. When she came to, she found the area all around her was dim and there was a terrible smell of burning bodies. Because the right side of her body was exposed to the bomb’s heat rays, her face had become swollen, and the skin on her right arm was peeling off and dangling down from the tips of her nails. She felt the intense pain when she put her hand down, so she raised it over her chest and headed to Nakano Village on foot with her neighbors.

Ms. Abe was later taken in at a makeshift relief station of Japan Steel Works in Funakoshi-cho (now part of Aki Ward), and stayed there for three days. After that, she was reunited with her father and finally returned to her parents’ home. In the time that followed, her family grated potatoes and applied them to her wounds, using a piece of cloth of a yukata (an informal cotton kimono), in place of gauze. Her burns gradually became keloid scars, and her mouth remained twisted. The fingers of her right hand bent backward and became stiff, and she had difficulty leading daily life.

Saburo, who returned to Japan from his military service at the end of the year, was advised to get divorced by those around him, but refused, and decided to remain married to her for his whole life. The following year, when Ms. Abe became pregnant with her first son, she was in the hospital for six months and underwent skin graft surgery. She gave birth to her first son in November 1946, her second son in 1949, and her first daughter in 1954.

Even though she was loved by her husband, some people teased her, saying, “Red Ogre is walking” when she walked outdoors. Her son’s classmates bullied him, calling him, “A child of the atomic bombing.” He sometimes returned home using a mountain route to avoid being seen. Ms. Abe said, “I always lead my life with my head down and cried with my children. How again and again I wanted to die.”

A-bomb survivors encouraged her to take a step forward to advance. The late Kiyoshi Kikkawa, who was later referred to as “Atomic Bomb Victim No. 1,” built a shack in front of the Atomic Bomb Dome. Ms. Abe shared her anxieties with people who gathered around the shack, and was deeply involved with early efforts to support A-bomb survivors. In 1956, she joined the group that submitted a petition appealing for support A-bomb survivors to the Diet with her 6-year-old second son. She wrote a poem, “Please put a warm hand, like sunlight at ten in the morning, / on survivors whose forgotten smiles lie somewhere in the distance / due to their grief and sorrow.” The poem was made into a song, and it was sung at anti-nuclear and other gatherings.

In 1964, Ms. Abe participated in the Hiroshima-Nagasaki World Peace Pilgrimage, planned by the late American peace activist Barbara Reynolds and others, and visited Europe, North America and the Soviet Union, talking about her experience for about three months. She also met with former President Harry S. Truman, who had ordered the A-bomb attacks. American people were kind to her, and she said the hatred she used to have had disappeared.

“I don’t want people to face the same kind of suffering,” said Ms. Abe. She intently continued talking about her A-bomb experience, but quit doing so about seven years ago. She now lives in a facility for the elderly. She feels she sowed seeds of peace, but can’t help feeling anger toward the Trump administration and the Japanese government that has followed in its footsteps. She said, “One atomic bomb did great damage. If another atomic bomb were used, the earth would be destroyed. How important peace is! I oppose the use and possession of nuclear weapons. I want you to speak about it all the time.” She feels so, even stronger, as we now see the 75th anniversary of the atomic bombing coming.

Teenagers’ Impressions

I’ll always keep compassion in mind

When Ms. Abe was young, she suffered terrible discrimination, and people said, “Red Ogre is coming” when she was walking about town. If I were in her shoes, I would shut myself away at home and lose the courage to live my life. Ms. Abe said, “I want you to communicate with others with a kind heart and a soft look,” and I learned that if we acted with compassion, the small circle of peace would widen. I’ll communicate with my friends and family like that. (Yurina Yunoki, 16)

I want to make “flowers” of activity bloom

Ms. Abe compares the anti-nuclear movement and her speaking activities to flowers and stresses, “The seeds I sowed grew little by little.” However, if a nation’s leader talks about peace in word only and does not advance disarmament, the shoots that have grown will die. Ms. Abe decided to carry out her mission as an A-bomb survivor and continued to talk about her painful experience of the atomic bombing. With her thoughts, I want to convey the importance of a peaceful world in my own words and make flowers bloom. (Yuna Okajima, 15)

I’ll send the message about the importance of peace to the world

Ms. Abe told us how important peace was and asked us to keep saving the peace. I can not only set up a major goal, but also send a message of the A-bombed city of Hiroshima and of the importance of peace to the world, using the social networking service, among other means. For that purpose, I need to learn about the exact state of current Hiroshima, the A-bomb experiences, and A-bomb materials, and then send the message. I want to post my message one by one.(Hitoha Katsura, 15)

(Originally published on January 13, 2020)