Survivors’ Stories: Tsuneo Sato, 86, Hiroshima: Stunned and shocked by total destruction of school in atomic bombing

Jan. 27, 2020

by Kyoko Niiyama, Staff Writer

Seeing human remains scattered on school grounds, he could only stand there

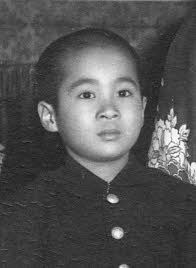

Tsuneo Sato, 86, lost many of his classmates and students in lower grades at school in the atomic bombing, when he was 12 and a sixth-grade student at a national elementary school. His school was completed destroyed and later closed down. Every time he visits the site, those sad memories come back to him.

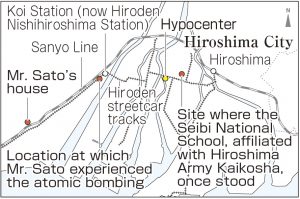

Mr. Sato went to the Seibi National School—affiliated with the Hiroshima Army Kaikosha—which was a school established for children of soldiers serving in the Imperial Japanese Army. The school was in downtown Hiroshima in Motomachi (now part of Naka Ward), an area lined with shops and military facilities. The soldiers from the Western Drill Ground frequently visited the school.

In April 1945, a time when Tokyo and other cities in Japan experienced repeated air raids by U.S. forces, third-to-sixth-grade students at his school evacuated to a temple in present-day Miyoshi, a city in northern Hiroshima prefecture. On August 5, another group of students evacuated from Hiroshima. For his part, Mr. Sato stayed in Hiroshima because, as he explains, “I was a troublemaker and afraid of wetting my bed while sleeping together with all my schoolmates.” The Record of the A-Bomb Disaster, issued by the City of Hiroshima, indicated that about 150 students at the Seibi National School had stayed behind in Hiroshima, as Mr. Sato had done.

During the war, there were days on which no classes were held at the school. August 6, however, was a school day. “As we were told that school lunch would be served that day, all the students must have looked forward to it from early morning,” said Mr. Sato. But as he had not done his homework for Japanese class scheduled for the first period that day, he imagined being scolded by the teacher and was worried. He left home somewhat later than usual to go to school.

He boarded a streetcar at Arate Station (now Kusatsuminami Station) close to his home in Kusatsu (now part of Nishi Ward), and looked out the window from a seat in the front. When the streetcar stopped for a traffic light just before arriving at Koi Station (now Hiroden-Nishihiroshima Station), he saw before him a sudden flash of light. As trained at school, he threw himself on the floor, pressing his eyes and ears with his fingers. Right after he crawled into a space between adult passengers who had fallen on each other, he heard a huge blast.

Since the streetcar had stopped next to a building, it avoided a direct hit from the A-bomb’s thermal waves. Nevertheless, the glass windows had shattered and sounds could be heard of adjacent galvanized sheet-iron roofs and mud walls crashing onto the streetcar. When he got outside, he heard a voice crying out. “It hurts, it hurts,” said a boy who stood on the nearby riverbank with glass fragments piercing his entire body. Because Mr. Sato and the other streetcar passengers were desperate to escape, no one was able to extend the boy a helping hand.

When he arrived at Koi Station, he saw injured people walking towards him from the direction of the downtown area. They suffered burns over their entire bodies, and peeled skin about a centimeter thick hung from their wrists. He could not bear witnessing such a fearful sight and returned to his home in Kusatsu.

About a month after the bombing, Mr. Sato went alone to his school. Everything around him was burned to the ground. The foundation of the school building, located about 700 meters from hypocenter, was the only thing left. On the school grounds, he found human remains that appeared to be the burnt hands or feet of children. All his classmates, who had already arrived at the school that day, were dead. “I felt numb and simply stood there,” Mr. Sato said. The school never opened its doors again, closing permanently in December 1945.

Mr. Sato later took over Kusatsu Hospital in Nishi Ward from his father Koichi, who founded the hospital, and served for many years in the position of hospital director as a neurologist. In 1985, based on a request from the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company, he wrote a brief account of his A-bombing experience on the streetcar. He had never voluntarily shared his memories of that day with anyone other than his family.

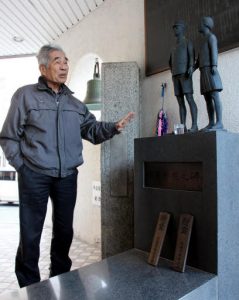

After the war, the Hiroshima YMCA was erected on the site where the Seibi National School had once stood. On the corner of the YMCA building’s site a monument stands as a memorial to the victims of the Seibi National School. Mr. Sato sometimes visits the monument. “We don’t need atomic bombs, which cruelly robbed the lives of innocent children.” He imagines the monument’s statues of young children happily holding hands in school uniforms to be his deceased classmates.

Impressions of those in their teens

Wars mustn’t be fought

“You can compete with others, but you shouldn’t fight each other,” was one comment by Mr. Sato that left an impression on me. According to him, by competing with people around you, you can improve yourself. But when you fight with others, all you do is end up hurting each other. I thought he was able to convey such ideas because he knows very well the horrors of the war, which was fought by adults when he was a child. (Hitoha Katsura, 14)

Saddened when I try to imagine his feelings

After listening to Mr. Sato’s recounting of his A-bombing experience, we went with him to the monument to mourn the victims of the Seibi National School. I sensed that Mr. Sato’s facial expression had clouded over a bit. I was saddened imagining his feelings when he discovered that his school had suddenly collapsed in the atomic bombing, killing many of his friends. It was at that time I thought once again that atomic bombs should be eliminated from all nations. (Yuno Nakano, 13)

(Originally published on January 27, 2020)

Seeing human remains scattered on school grounds, he could only stand there

Tsuneo Sato, 86, lost many of his classmates and students in lower grades at school in the atomic bombing, when he was 12 and a sixth-grade student at a national elementary school. His school was completed destroyed and later closed down. Every time he visits the site, those sad memories come back to him.

Mr. Sato went to the Seibi National School—affiliated with the Hiroshima Army Kaikosha—which was a school established for children of soldiers serving in the Imperial Japanese Army. The school was in downtown Hiroshima in Motomachi (now part of Naka Ward), an area lined with shops and military facilities. The soldiers from the Western Drill Ground frequently visited the school.

In April 1945, a time when Tokyo and other cities in Japan experienced repeated air raids by U.S. forces, third-to-sixth-grade students at his school evacuated to a temple in present-day Miyoshi, a city in northern Hiroshima prefecture. On August 5, another group of students evacuated from Hiroshima. For his part, Mr. Sato stayed in Hiroshima because, as he explains, “I was a troublemaker and afraid of wetting my bed while sleeping together with all my schoolmates.” The Record of the A-Bomb Disaster, issued by the City of Hiroshima, indicated that about 150 students at the Seibi National School had stayed behind in Hiroshima, as Mr. Sato had done.

During the war, there were days on which no classes were held at the school. August 6, however, was a school day. “As we were told that school lunch would be served that day, all the students must have looked forward to it from early morning,” said Mr. Sato. But as he had not done his homework for Japanese class scheduled for the first period that day, he imagined being scolded by the teacher and was worried. He left home somewhat later than usual to go to school.

He boarded a streetcar at Arate Station (now Kusatsuminami Station) close to his home in Kusatsu (now part of Nishi Ward), and looked out the window from a seat in the front. When the streetcar stopped for a traffic light just before arriving at Koi Station (now Hiroden-Nishihiroshima Station), he saw before him a sudden flash of light. As trained at school, he threw himself on the floor, pressing his eyes and ears with his fingers. Right after he crawled into a space between adult passengers who had fallen on each other, he heard a huge blast.

Since the streetcar had stopped next to a building, it avoided a direct hit from the A-bomb’s thermal waves. Nevertheless, the glass windows had shattered and sounds could be heard of adjacent galvanized sheet-iron roofs and mud walls crashing onto the streetcar. When he got outside, he heard a voice crying out. “It hurts, it hurts,” said a boy who stood on the nearby riverbank with glass fragments piercing his entire body. Because Mr. Sato and the other streetcar passengers were desperate to escape, no one was able to extend the boy a helping hand.

When he arrived at Koi Station, he saw injured people walking towards him from the direction of the downtown area. They suffered burns over their entire bodies, and peeled skin about a centimeter thick hung from their wrists. He could not bear witnessing such a fearful sight and returned to his home in Kusatsu.

About a month after the bombing, Mr. Sato went alone to his school. Everything around him was burned to the ground. The foundation of the school building, located about 700 meters from hypocenter, was the only thing left. On the school grounds, he found human remains that appeared to be the burnt hands or feet of children. All his classmates, who had already arrived at the school that day, were dead. “I felt numb and simply stood there,” Mr. Sato said. The school never opened its doors again, closing permanently in December 1945.

Mr. Sato later took over Kusatsu Hospital in Nishi Ward from his father Koichi, who founded the hospital, and served for many years in the position of hospital director as a neurologist. In 1985, based on a request from the Hiroshima Electric Railway Company, he wrote a brief account of his A-bombing experience on the streetcar. He had never voluntarily shared his memories of that day with anyone other than his family.

After the war, the Hiroshima YMCA was erected on the site where the Seibi National School had once stood. On the corner of the YMCA building’s site a monument stands as a memorial to the victims of the Seibi National School. Mr. Sato sometimes visits the monument. “We don’t need atomic bombs, which cruelly robbed the lives of innocent children.” He imagines the monument’s statues of young children happily holding hands in school uniforms to be his deceased classmates.

Impressions of those in their teens

Wars mustn’t be fought

“You can compete with others, but you shouldn’t fight each other,” was one comment by Mr. Sato that left an impression on me. According to him, by competing with people around you, you can improve yourself. But when you fight with others, all you do is end up hurting each other. I thought he was able to convey such ideas because he knows very well the horrors of the war, which was fought by adults when he was a child. (Hitoha Katsura, 14)

Saddened when I try to imagine his feelings

After listening to Mr. Sato’s recounting of his A-bombing experience, we went with him to the monument to mourn the victims of the Seibi National School. I sensed that Mr. Sato’s facial expression had clouded over a bit. I was saddened imagining his feelings when he discovered that his school had suddenly collapsed in the atomic bombing, killing many of his friends. It was at that time I thought once again that atomic bombs should be eliminated from all nations. (Yuno Nakano, 13)

(Originally published on January 27, 2020)